| Gastroenterology Research, ISSN 1918-2805 print, 1918-2813 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, Gastroenterol Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://gr.elmerpub.com |

Original Article

Volume 000, Number 000, March 2025, pages 000-000

Incidence of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Children

Joanna Wiczynska-Ryla, b, c , Aneta Krogulskaa, b

aDepartment of Pediatrics, Allergology and Gastroenterology, Collegium Medicum Bydgoszcz, Nicolaus Copernicus University, 87-100 Torun, Poland

bThe authors contributed equally to this work.

cCorresponding Author: Joanna Wiczynska-Ryl, Department of Pediatrics, Allergology and Gastroenterology, Collegium Medicum Bydgoszcz, Nicolaus Copernicus University, 87-100 Torun, Poland

Manuscript submitted December 6, 2024, accepted February 28, 2025, published online March 25, 2025

Short title: Incidence of IBD in Children

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/gr2007

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Many of the patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are children and adolescents, and the incidence of pediatric IBD is increasing. However, understanding epidemiological trends is crucial for effective prevention and treatment and reducing the local and global burden of IBD. Little data exist regarding the incidence of IBD in the child population in the Kujawsko-Pomorskie Voivodeship. The aims of this study were to evaluate the incidence of IBD in the period 2011 - 2022 and to compare the data regarding three types of IBD, namely ulcerative colitis (UC), Crohn’s disease (CD), and unclassified inflammatory bowel disease (IBD-U), from the first half, i.e. 2011 - 2016, to the second half, i.e. 2017 - 2022.

Methods: This retrospective study analyzed the medical records of 118 IBD patients hospitalized at the Department of Pediatrics, Allergology and Gastroenterology from the central-northern part of Poland.

Results: Of the 118 patients diagnosed with IBD, 48 (40.68%) had CD, 57 (48.31%) had UC, and 13 (11.01%) had IBD-U. Between 2011 and 2016, 48 new IBD patients were diagnosed, with a further 70 new cases added between 2017 and 2022, representing a significant increase over the period (P = 0.033). Also, a significant increase was seen for UC, i.e. rising from 19 new cases between 2011 and 2016, to 38 between 2017 and 2022 (P = 0.015). The increase in CD was not significant.

Conclusion: The incidence of pediatric IBD in the central-northern district of Poland is lower than other countries, it nonetheless appears to be increasing, particularly in children with UC. The number of IBD diagnoses in children has increased by nearly 50% over the last 6 years.

Keywords: Inflammatory bowel disease; Children; Incidence; Poland

| Introduction | ▴Top |

The term inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is used to refer to a group of conditions characterized by a chronic inflammatory process with a complex, unclear, multifactorial etiology and a course including periods of exacerbation and remission. The two most common forms of IBD are Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), with unclassified IBD (IBD-U) being less frequently diagnosed. Both genetic susceptibility and environmental exposure play roles in the not fully understood pathogenesis of IBD, eliciting changes in the gut microbiome and resulting in activation of the immune system [1, 2].

Whole genome studies have identified variants in more than 150 genes that increase the risk of IBD [3]. For example, a strong association has been demonstrated between polymorphisms of the NOD2/CARD15 gene and CD [4]. Studies suggest that genetic factors may play a greater role in early-onset IBD, i.e. in children, and the presence of IBD in a first-degree relative significantly increases the chance of IBD in a patient [2].

Although genetic predisposition certainly plays a role in the development of IBD, environmental factors appear to be dominant in shaping the increasing trend of the disease. The sum of environmental factors such as western diet, infection, smoking, stress, urbanization, and medication to which a human is exposed during the lifetime, recently termed the “exposome”, can play an important role in the pathogenesis of IBD [5].

The western diet characterized by a high intake of protein, red meat, saturated fats and sugars, as well as low fiber intake, deficiencies in vitamin D and micronutrients can modify the composition of the gut microbiota [6]. An association has also been shown between early risk factors during the prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal periods, such as delivery by cesarean section and lack of breast milk feeding and the development of IBD [7, 8], although there are studies that have not confirmed these assumptions [9]. Interestingly, cigarette smoking or passive exposure to tobacco smoke has been shown to be a protective factor against UC, but not CD [10]. In addition, while psychological stress can trigger a relapse or exacerbation of IBD, regular exercise has been shown to be a protective factor [11].

It seems that all the factors mentioned above have an impact on the changes in gut microbiota, which has been demonstrated to affect a vast number of biological processes, including immunity, and play a critical role in the pathogenesis of IBD. At the same time, gut microbiome composition responds to lifestyle and environmental factors. Such factors change greatly as societies become industrialized, acquiring access to antibiotics and better sanitization, as well as transitioning to a westernized diet [12, 13]. A number of studies indicate that IBD is more common in urban than rural regions and is correlated with socioeconomic status [1, 14]. Understanding the risk factors for the disease may help reduce the increase in the incidence of IBD and implement new methods of prevention and treatment of this important disease.

The last century has seen a significant increase in the incidence of IBD, especially in the pediatric population, with a particular increase over the last 50 years, especially in developing countries. Currently, the highest prevalence of IBD is recorded in North America, Western Europe, and Oceania [15]. In 2020, approximately 0.2% of the European population suffered from IBD [7]. It is assumed that, worldwide, approximately 20-25% of patients are diagnosed in childhood, of whom 5% present an early onset of symptoms, i.e. under 5 years of age [1, 16]. It has been shown that the incidence is rising in both high-income and low-income countries [17].

A systemic review from the period 1985 - 2018 by Sykora et al identified the highest incidence of pediatric-onset IBD in Europe (0.2 - 23/100,000 person/year) and North America (1.1 - 15.2/100,000), while the lowest incidences were reported in Oceania (2.9 - 7.2/100,000), Asia (0.5 - 11.4/100,000), Latin America (0.2 - 2.4/100,000), and Africa (0.0 - 0.9/100,000) [18]. Interestingly, while the highest incidence of CD was noted in North America (13.9/100,000) and Europe (12.9/100,000), the greatest incidence of UC was observed in Europe (15.0/100,000), followed by North America (10.6/100,000). Similarly, the highest incidence of IBD-U was also noted in Europe (3.6/100,000) and North America (2.1/100,000) [18]. In a study of children treated in New Zealand between 2010 and 2020, Rajasekaran et al found the incidence of IBD to be 14.1 per 100,000 in those of South Asian descent and 4.3 per 100,000 of non-South Asian descent [19]. In turn, based on pooled estimates derived from a systematic review of data from 1950 to 2020, Forbes et al determined the following annual incidences among children from Australia and New Zealand: 4.1 per 100,000 children/year for IBD, 2.3 for CD, and 0.9 for UC [20].

A population-based retrospective cohort study of all children diagnosed with IBD in Ontario, Canada, from 1994 through 2009 showed that the incidence of IBD increased from 9.4 per 100,000 children in 1994 to 13.2 per 100,000 children in 2009 [21]. An overwhelming amount of data suggests that the global incidence is increasing in both adult and child populations [18]. The prevalence of IBD in Canada is projected to increase from 0.7% in 2018 to 1% of the population in 2030 [14]. It is also increasing in the newly industrialized countries of Africa, Asia, and South America, reflecting the rise in IBD prevalence observed in the 1990s in Western countries, which were at similar stage of development at the time [15].

A recent multicenter study by Lewis et al showed that the incidence of IBD peaked in the third decade of life [22]. While CD affects twice as many women as men in Europe and the USA, more men are affected than women in Asia. However, no such difference in incidence has been noted for UC with regard to sex nor continent [23]. Studies on 16 regions in Europe, North America, Australia, and New Zealand regarding the occurrence of IBD according to sex and age found that girls had a lower risk of CD than boys until puberty, at which point there is a reversal, with teenage girls and women having a higher risk than teenage boys and men. However, there was no significant difference in the incidence of UC between female and male patients up to the age of 45 years, although after this age, men had a 20% higher incidence rate of UC than women. In early childhood (age group: 5 - 9 years), girls had a 22% higher risk of being diagnosed with UC than boys [23].

The incidence of IBD in children varied according to population, geographical location, and industrialization. However, the data are variable and sparse. The incidence of IBD in children has also been reported to be growing in the Czech Republic, the country neighboring Poland, rising from 3.8 per 100,000/year in 2002 to 14.7 per 100,000/year in 2017 [17]. Data from the Polish National Health Fund indicate that in 2020, 23,574 patients were diagnosed with CD, including 1,730 children and adolescents aged under 19 years, and 73,235 with UC, including 2,064 under the age of 19 years. In Poland, in 2018, the crude annual incidence of CD was 4.7 per 100,000 people and for UC was 12.5/100,000. In children under 10 years, the incidence of CD was 0.9 per 100,000 population and that of UC was 1.6/100,000. The incidence was higher in the 10 to 19 years age group, being 7.2/100,000 for CD and 9.5/100,000 for UC [24].

So far, no data have been published regarding the incidence of IBD in children from our region, i.e. in the Kujawsko-Pomorskie Voivodeship.

The aim of the study was to determine the incidence of IBD in children between 2011 and 2022 in the Kujawsko-Pomorskie Voivodeship, located in the central-northern area of Poland.

As few epidemiological studies have been performed on IBD in children in Poland, our study may constitute an introduction to further multicenter studies, which will allow for a more extensive assessment of epidemiological data on IBD in the Polish pediatric population over time.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

This study included the medical records of 118 children (2 - 18 years old) with IBD. All patients were Caucasian, and all had been hospitalized at the Department of Pediatrics, Allergology and Gastroenterology, Collegium Medicum Bydgoszcz, Nicolaus Copernicus University, Torun, between January 1, 2011 and December 31, 2022.

The present epidemiological study retrospectively compared the incidence of IBD over time to determine the epidemiological trend in the condition. To assess potential changes over time, patient data were analyzed during the two analyzed time intervals: 2011 - 2016 and 2017 - 2022.

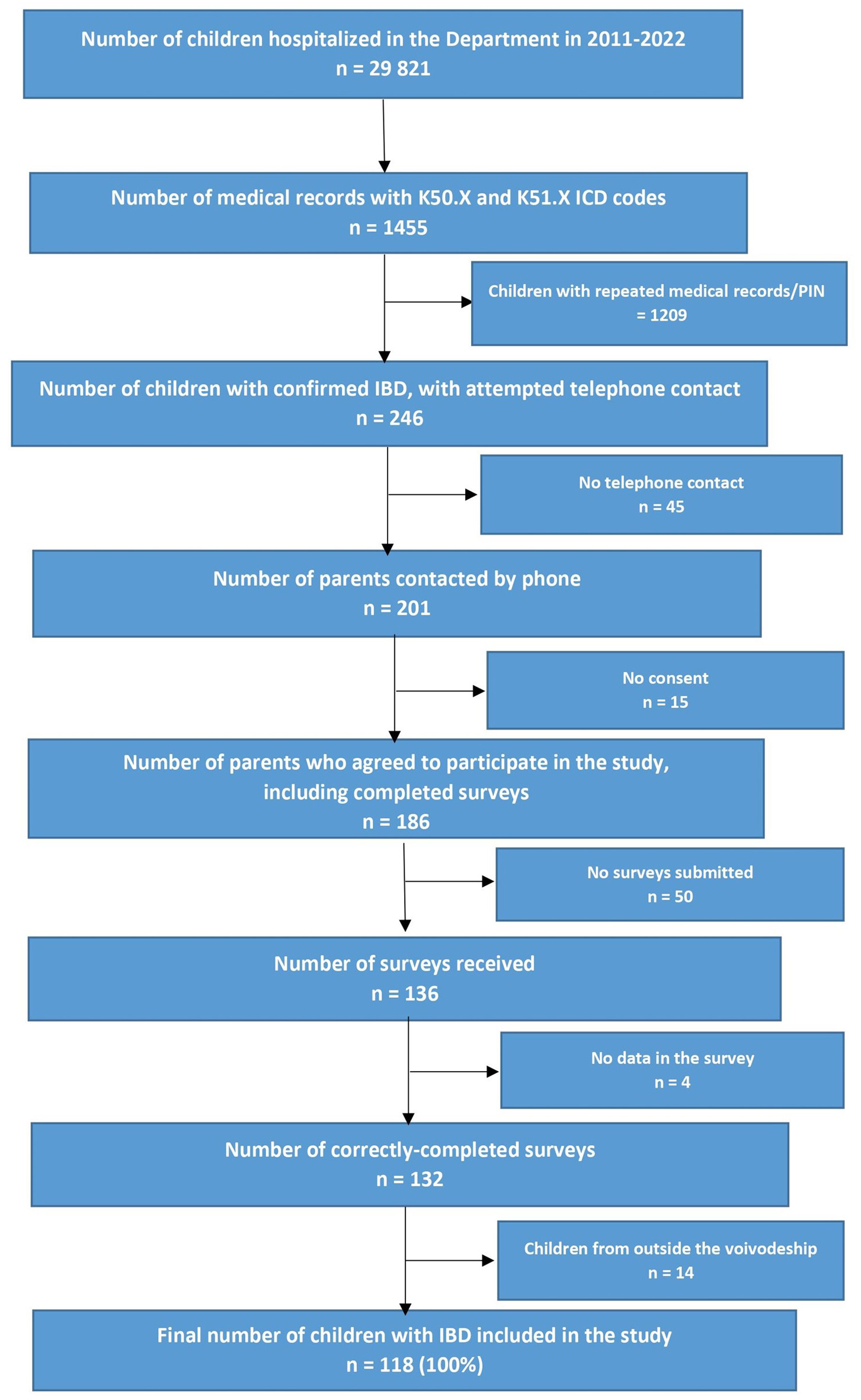

According to the flow chart of study design (Fig. 1), 246 patients with IBD were diagnosed at the department during 2011 - 2022. The IBD patients and the type of IBD were retrieved from electronic medical records, from the hospital database; this was accomplished by searching for diagnosis codes of K50.XX for CD and K51.XX for UC according to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10 codes). Of the selected codes, those with a repeatable personal identification number (PIN) were verified.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Flow chart of study design. |

The children, from the voivodeship, were referred by their GPs, from lower-reference hospitals or from gastroenterology outpatient clinics. The final diagnosis of IBD was established at the department, i.e. at a single university center (the one in our voivodeship, and at the same time the only one dedicated specifically to the diagnosis and treatment of children with IBD) following which the patients remained under the care of our center.

Before taking part in the study, telephone calls were made to all selected patients with the aim of informing them about the study and requesting permission to take part. After agreeing to participate in the study, the respondents’ guardians were sent electronic copies of the study questionnaires. Due to the lack of telephone contact, consent to the study, and incomplete data in the surveys, we included only 118 children in the study (i.e. 100% correctly completed surveys). All children included in the study were treated in our department or outpatient clinic. The study questionnaires consisted of questions about the type of IBD, the age and season of the first symptoms, the age and year of diagnosis, sex, place of residence, use of biological therapy, and family history of IBD. The characteristics of the study group are presented in Table 1.

Click to view | Table 1. Characteristics of the Study Group at the Time of Data Collection |

IBD was diagnosed according to the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) recommendations, based on clinical, endoscopic, histopathological, radiological, and serological criteria [2]. In cases where it was difficult to define CD and UC based on the endoscopic, imaging, and histopathological and laboratory examinations associated with the medical reports, the terminology IBD-U was applied. The diagnosis was based on the “pediatric inflammatory bowel disease (PIBD)-class” classification algorithm allowing the condition to be allocated into PIBD sub-classes based on 23 features that are typical of CD. Briefly, if no such features exist, the disease should be classified as UC, while if at least one feature exists, it should be classed as atypical UC, IBD-U or CD based on the combinations of features. This algorithm is characterized by high sensitivity and specificity in differentiating UC from CD and IBD-U [2, 25].

In addition, the number of new IBD cases per 100,000 children per year in the local voivodeship (Kujawsko-Pomorskie) was calculated based on statistical yearbooks. The season of IBD onset was determined as follows: spring as March, April and May, summer as June, July and August, autumn as September, October and November, and winter as December, January and February. As gaps were present in the medical records, the severity of the course of the disease was determined based on the need for biological treatment, i.e. biological treatment was associated with a severe course, and no such treatment with a mild or moderate course. A diagnosis of IBD awarded under the age of 6 years indicated very early-onset IBD (VEO-IBD). The children were divided into three groups in terms of age of diagnosis, namely between 2 and 5 years of age, between 6 and 10, and between 11 and 17, in accordance with the Pediatric Paris classification [26]. Patients lacking adequate data, or who were resident in other voivodeships were excluded from the study.

The present study constitutes a fragment of another study on IBD in children, analyzing mainly risk factors, which is currently ongoing in our department.

The study was approved by the Bioethical Committee of the Collegium Medicum in Bydgoszcz, Nicolaus Copernicus University in Torun (KB 494/2022). All participants gave their written informed consent to take part in the study. This study was conducted in compliance with the ethical standards of the responsible institution on human subjects as well as with the Helsinki Declaration.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data were described as number of cases (N), mean value (M), standard deviation (SD), minimum (Min), and maximum (Max). Qualitative data were represented as number of cases (N) and their percentage of the study group. The analyses were performed in Python 3.8.10 (developed by Python Software Foundation) using the following libraries: pandas (v. 1.4.3), scipy (v. 1.10.1), numpy (v. 1.24.3), pingouin (v. 0.5.3), statsmodels (v. 0.14.0), and rpy2 (v. 3.5.14). Continuous variables were compared using Student’s t-test, Mann-Whitney U-test, and Kruskal-Wallis test as appropriate. Fisher’s exact tests and the Chi-square test were used to compare categorical variables. Equality of groups was checked using the Chi-square test. A proportions test was used to determine the ratios of the groups. When selecting tests for comparisons of quantitative variables, the assumptions about the normality of the distribution of variables in subgroups were followed, and the hypothesis of normality was verified with the Shapiro-Wilk test. Visualizations were also made in Python using the matplolib library (v. 3.1.3).

| Results | ▴Top |

A total of 118 (100%) children with IBD were included in the study. These included 57 (48.30%) with UC, 48 (40.68%) with CD, and 13 (11.02%) with IBD-U.

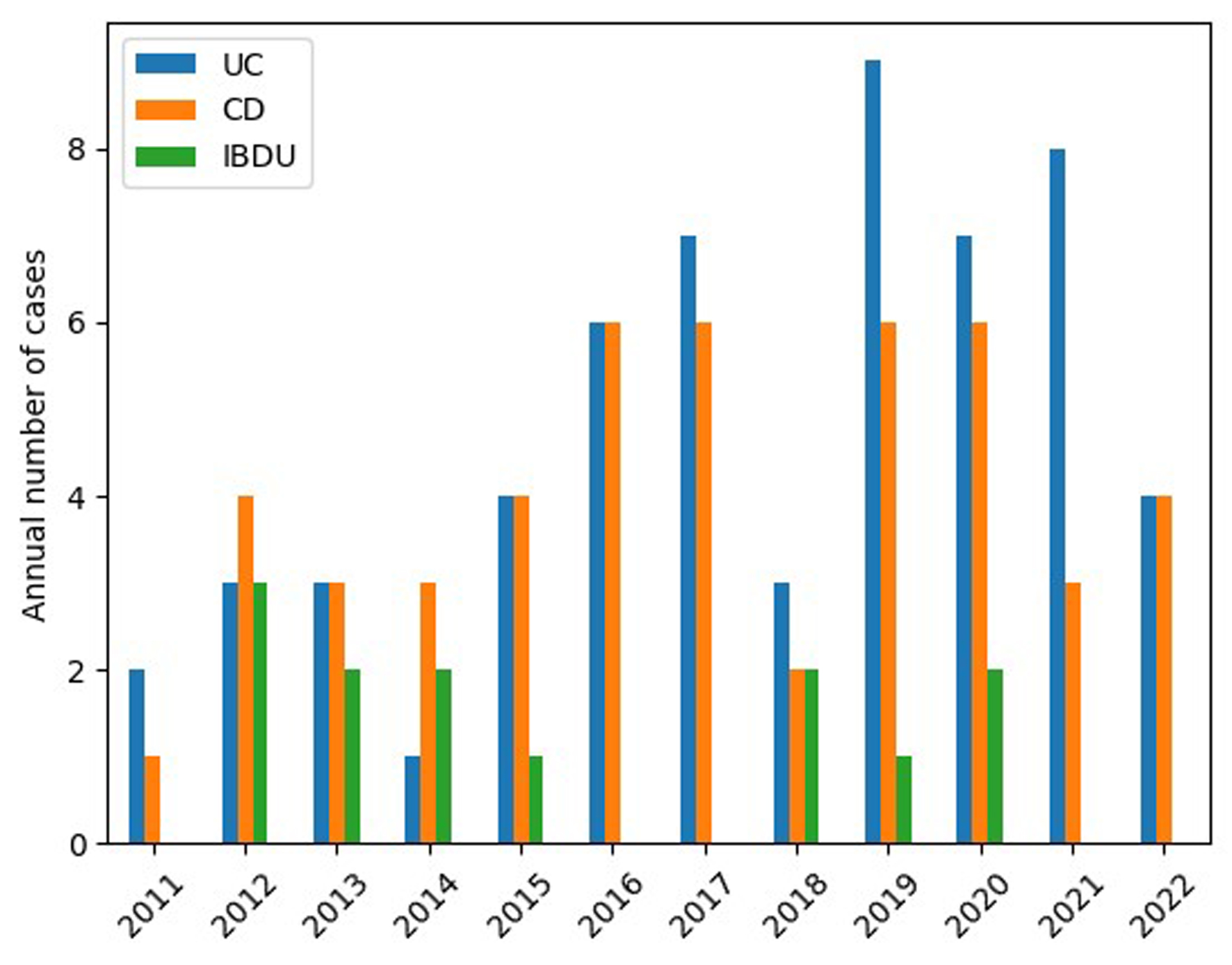

In the first analyzed period (2011 - 2016), IBD was diagnosed in 48 children, i.e. UC in 19 (39.58%), CD in 21 (43.75%), and IBD-U in eight (16.67%). In the subsequent period (2017 - 2022), IBD was found in 70 patients, i.e. UC in 38 (54.29%), CD in 27 (38.57%), and IBD-U in five (7.14%). The number of new diagnoses is shown by year in Figure 2.

Click for large image | Figure 2. Number of new cases of UC, CD, and IBD-U per year. CD: Crohn’s disease; IBD-U: unclassified inflammatory bowel disease; UC: ulcerative colitis. |

It can be seen that the number of new patients with IBD diagnoses increased significantly over time, and was 46% higher between 2017 and 2022 than between 2011 and 2016 (P = 0.034). The significant increase in new IBD diagnoses in children related specifically to UC: 19 new UC diagnoses were noted in the first analyzed period, and this value doubled to 38 in the subsequent period (P = 0.015). Although the number of diagnosed CD cases rose from 21 in the earlier period to 27 in the next, this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.179).

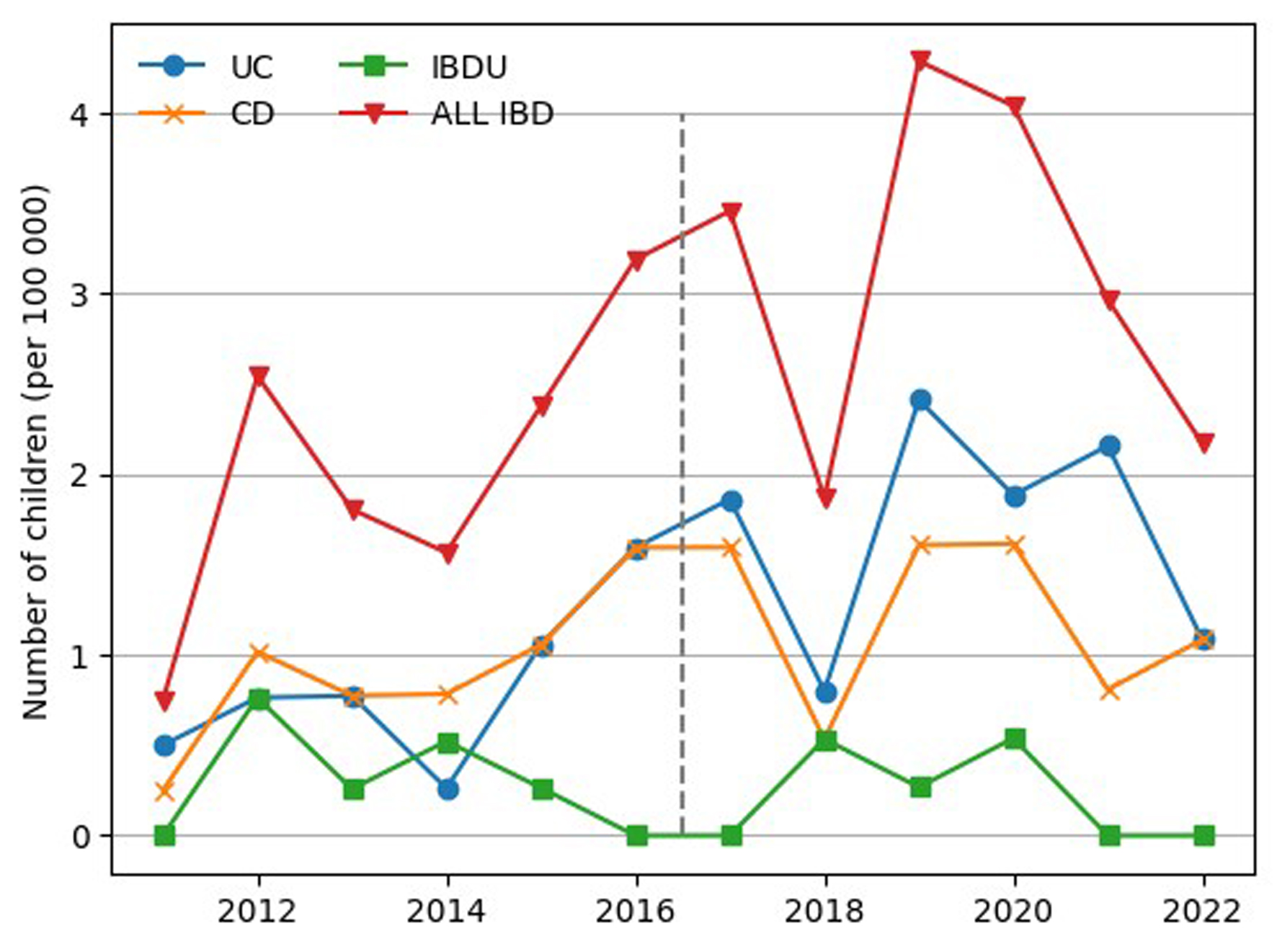

The mean incidence of IBD was 2.9 per 100,000 children/year, ranging from 0.9 to 4.5/100,000/year (1.3/100,000 for UC and 1.1/100,000 for CD). The number of new cases of IBD per 100,000 children in the Kujawsko-Pomorskie voivodship is presented according to type of IBD in Figure 3.

Click for large image | Figure 3. Number of children with newly diagnosed IBD, UC, CD, and IBD-U (per 100,000 children) in the Kujawsko-Pomorskie voivodeship. CD: Crohn’s disease; IBD-U: unclassified inflammatory bowel disease; UC: ulcerative colitis. |

The mean age at onset of IBD for the period 2011 - 2022 was 10.48 ± 4.57 years (11.40 ± 4.25 for UC; 10.06 ± 4.74 for CD) and mean age at diagnosis was 11.67 ± 4.15 years (12.47 ± 3.52 for UC; 11.38 ± 4.50 for CD); both ages were higher in the second period; however, a similar period was noted between onset and diagnosis in both periods.

The mean age of onset of first symptoms in children with IBD extended significantly from 9.33 ± 4.95 years in the first period to 11.27 ± 4.14 years in the second (P = 0.023). For CD, the mean age of onset rose from 9.81 ± 4.64 years in the first period to 10.26 ± 4.90 in the second (P = 0.594). For UC, the mean age of onset increased from 10.26 ± 5.42 to 11.97 ± 3.47 years (P = 0.363).

The mean age of diagnosis of IBD rose significantly from 10.75 ± 4.51 years in the first period to 12.3 ± 3.79 years in the second (P = 0.046). However, for CD, it rose from 10.71 ± 4.57 to 11.89 ± 4.47 years (P = 0.296), and for UC, it rose slightly from 12.11 ± 3.94 to 12.66 ± 3.32 years (P = 0.734). IBD was also diagnosed more frequently in older patients in the later study group.

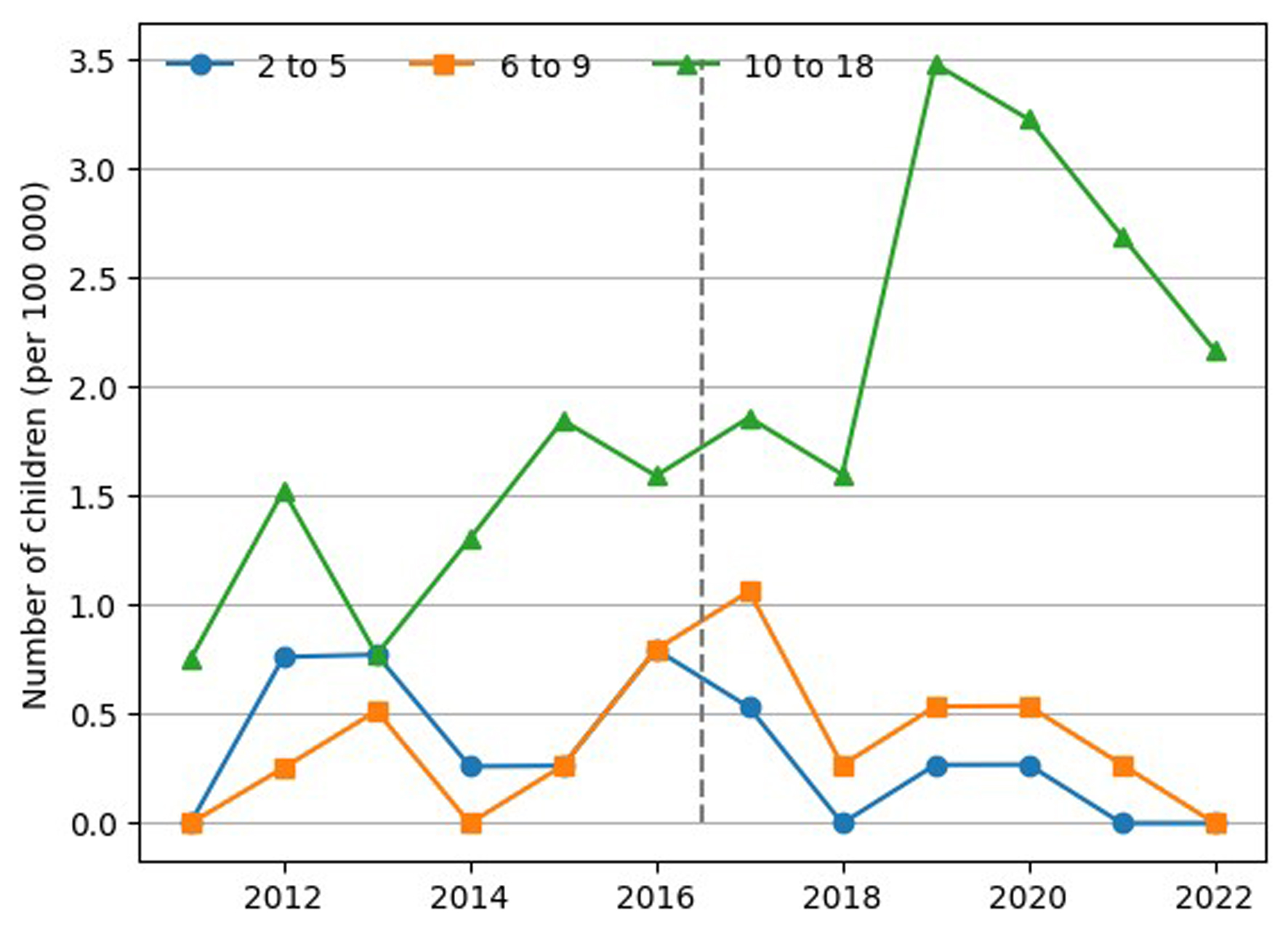

It can be seen that IBD was also mainly diagnosed in the group of children aged > 10 years, with a significant increase observed in 2018 (Fig. 4).

Click for large image | Figure 4. Trend in IBD incidence in children by age subgroup. IBD: inflammatory bowel disease. |

The mean time between the onset of first symptoms of IBD and the establishment of diagnosis for the period 2011 - 2022 was 1.19 ± 2.15 years (1.07 ± 2.19 for UC; 1.31 ± 2.27 for CD).

Similar times between the onset of the first symptoms and the establishment of the diagnosis were found between the two periods (P = 0.338). In the earlier period, i.e. between 2011 and 2016, these times equated to 1.42 ± 2.29 years for IBD, 0.9 ± 1.09 years for CD, and 1.84 ± 3.24 years for UC. In contrast, between 2017 and 2022, these values were 1.03 ± 2.06 years for IBD, 1.63 ± 2.86 for CD (P = 0.566), and 0.68 ± 1.3 years for UC (P = 0.407).

Children with early-onset IBD, i.e. under 6 years of age, were a minority in both 2011 - 2016 and 2017 - 2022. While children aged over 6 years demonstrated more UC diagnoses in 2017 - 2022, no such increase was observed among younger children (Table 2).

Click to view | Table 2. Children With IBD With Regard to Age at the Time of Diagnosis, Onset of the First Symptoms, Sex, the Severity of Course, and Place of Residence in the Period 2011 - 2022 |

No significant differences in the percentage of diagnosed patients with regard to sex or IBD type were noted between the first and second time periods (P > 0.05). In both periods, IBD was diagnosed in approximately 56% of boys; male sex also predominated in both UC and CD (Table 2).

The frequency of biological treatment differed significantly between the two periods (P = 0.024). A higher proportion of patients experienced more severe disease in the first period than in the second period; in addition, biological therapy was more commonly used for UC in the second period compared to the first (Table 2).

In both time periods, children living in city areas demonstrated a higher incidence of IBD, including UC and CD, compared to rural areas; however, this difference was not significant (Table 2).

About 15% of children had a first-degree relative who also had IBD. Among these respondents, inheritance from the maternal side was dominant. No significant differences in the number of diagnosed children were found with regard to the type of IBD or presence of IBD in the family (P = 0.174) (Table 1).

No significant relationship was noted between the type of IBD and the time of onset of the disease, with regard to season, regardless of the period analyzed. However, it is worth emphasizing that the percentage of patients in whom the onset of the disease occurred in winter remained basically unchanged, regardless of the period studied, and what is more, it was the lowest compared to the other seasons. However, some seasonal fluctuations were observed in the other seasons. Although not statistically significant, in the entire analyzed period, the highest number of new cases of IBD (including UC) was observed in spring and autumn, while for CD in autumn and summer. Comparing the second analyzed period, in the period 2017 – 2022, a significant increase in new cases was observed in autumn with respect to IBD, including both UC and CD, while a decrease was observed in spring and summer with respect to IBD, including only CD (Table 3).

Click to view | Table 3. Number of Patients According to the Season of the First Symptoms |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

The results of our comparative analysis of IBD diagnoses between the two time periods are in line with the widely observed global upward trends in the incidence of both CD and UC. However, a statistically significant increase in the incidence was only observed in children with UC. While children with CD predominated in the first study period, UC was prevalent in the second.

Data on the incidence of PIBD vary between studies; however, our findings are similar to those obtained in another Polish study, which report an incidence of 2.7 per 100,000 people/year [27]. This figure is rather low compared with studies from another populations, though higher than the globally incidence of IBD in 2019, which was 0.95 per 100,000 [28].

The median incidence rate of IBD per 100,000 children/year in recent studies from Croatia (one single-center and one multicenter) varies between 7.05 and 9.89, varying across age groups and types of IBD (2.63 for CD, 3.87 for UC, and 0.55 for IBD-U) [29, 30].

Kuenzig et al conducted a systematic review of 131 studies from 48 countries on the incidence and prevalence of IBD in people under 21 years of age between 2000 and 2020. It was found that 82 studies from 38 countries presented with both CD and UC. The incidence of CD was higher than UC in almost all analyzed regions. The ratio of CD to UC was the highest in Canada (approximately 9:1), and the lowest in Moldova, Malta, Italy, Poland, and Island (approximately 0.1 - 0.4:1). In most studies, the ratio was approximately 2 to 3:1. Trends in the CD/UC ratio were stable over time [31]. Also, a US study found CD to be twice as common as UC in children between 2007 and 2016 [32]. CD also dominated in the retrospective Croatian study, conducted in a similar period as our study (i.e. 2012 - 2021), where 107 children were diagnosed, with 43.9% having UC, 55.1% having CD, and 0.9% having IBD-U [30].

However, in contrast, UC was diagnosed in 54%, CD in 33%, and IBD-U in 13% in a study of 756 patients between 1987 and 2017 in Argentina; in addition, the incidence of CD was found to rise from 2007 to 2017 [33].

Moreover, in a survey study conducted among pediatric gastroenterologists from Latin America (i.e., Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, El Salvador, Mexico, Nicaragua, Peru, Uruguay, and Venezuela) including 607 patients diagnosed within the time frame of 2005 - 2016, UC was diagnosed in 475 (78.3%), CD in 104 (17.1%), and IBD-U in 28 (4.6%). The UC/CD ratio was 4.6:1; the annual frequency of UC increased 5.1-fold, whereas that of CD increased 3.4-fold [34].

Our findings indicate that throughout the analyzed period, more children suffered from UC than CD (our mean ratio CD/UC was 0.8), although CD dominated in the first period and UC later on, which is comparable to the results from studies in the Moldova, Malta, Italy, Poland [31], and Latin America [34]. It is not clear why CD was rarer in our study in comparison to high-income countries. But for now, the only explanation is that environmental factors, life style, diet, microbiome or genetic background in Poland are more similar to Moldova, Malta, Italy, and Island.

The rather low incidence of IBD in our study may be also due to its methodology, i.e. the study was retrospective in nature, all participants were patients from a single university center, and the population likely differed according to genes, microbiome or the environment: the region of central-northern area of Poland has many woods, lakes, and rivers, and is not so highly populated and polluted. A prospective population-based study in 13 countries or regions in Asia-Pacific suggests that the prevalence of IBD is higher in densely populated areas of Asia and that the prevalence may be associated with increased urbanization [28].

Our data indicate a 46% increase in new cases of IBD in the later period (2017 - 2022) compared to 2011 - 2016; this is consistent with the generally observed trend in the global pediatric population and is probably related to changes in the microbiome and the environment. The time-trend analysis illustrated an increasing or stable incidence in North America, Europe, and Oceania and an increasing incidence in newly industrialized countries in Asia, the Middle East, and Africa [18]. According to a cross-sectional study based on aggregated data performed by Long et al, the incidence and prevalence of IBD among children and adolescents stabilized between 1990 and 2019, but are significantly on the rise in some countries and regions [28]. A multicenter retrospective study by Choe et al reported an upward trend in CD diagnoses in South Korea between 2017 and 2020 [35]. Although CD demonstrated an increasing trend in our study, only UC was found to display a significant increase. Similarly, pediatric UC was found to be more commonly diagnosed than CD in populations from Finland [36] and Poland [27], where the incidence of UC exceeds that of CD [18]; however, most other studies indicate the opposite [31].

In Germany, a country neighboring with Poland, the age-standardized incidence rate per 100,000 person-years for IBD increased from 4.6 in 2000 to 8.2 in 2014 and projected incidence rates are 12.9 in the year 2025 and 14.9 in 2030 [37].

A better understanding of the relationships between environmental factors and the pathogenesis of IBD may help to understand the observed differences in the incidence of UC and CD between different populations and geographical regions.

The incidence of PIBD peaks during adolescence. Significant differences have been noted between studies with regard to age at diagnosis. In our study, IBD was also mainly diagnosed in the group of children aged over 10 years: the mean age at diagnosis was 11.67 years. An analysis conducted in Lower Silesia, also from Poland, between 2016 and 2018, found the mean age at diagnosis of IBD to be 13.1 ± 3.8 years [38]. A study of children with IBD from the neighboring Czech Republic in the period 2002 - 2017 found the median age at diagnosis to be 13.9 ± 4.9 years [17]. Similarly, the median age at diagnosis was 14.1 years in Split-Dalmatia County. Additionally, as in our study, patients diagnosed with UC were older compared to those with CD [30].

Data from the children’s hospital in England indicate a higher incidence in patients aged 10 to 18 years compared to younger children [39]. In contrast, Benchimol et al observed the greatest increase in IBD between 1994 and 2009 in Canada to be in VEO-IBD, i.e. among children aged under 6 years [21]. Countries such as Saudi Arabia, Finland, France, and UK have shown declining or stable incidence rates among the youngest children but increasing rates in older children; in contrast, Canada has reported increasing rates in the youngest children but stable rates in older children [31].

Our present data indicate a lower mean age of diagnosis in both studied periods, i.e. 10.75 ± 4.51 years in the first period and 12.3 ± 3.79 years in the second. This lower age may be due to population differences, better diagnostic methods, better access to health care facilities or other environmental conditions leading to faster manifestation of the disease.

Another comparison of IBD diagnoses during two time periods (1990 - 1995 and 2003 - 2008) by Henderson et al in Scotland indicated a steadily increase in the number over time, with the age at diagnosis falling from 12.7 to 11.9 years (P = 0.003) [40]. In contrast, our data indicate that diagnoses are being established in increasingly older patients. Similar results were obtained by Ye et al who identified the highest prevalence of IBD to be in a group of US children over 10 years of age, and that the prevalence in this age group increased over the period 2007 to 2016 [32].

The mean time from the first symptoms to diagnosis in our study was 1.19 ± 2.15 years; this period was 1.42 ± 2.29 years in the first period and 1.03 ± 2.06 years in the second. Although these differences were not significant, they raise hope for increasingly accurate diagnosis and faster disease detection. Probably, due to the education and popularization of fecal calprotectin testing, the diagnoses were made insignificant faster in the second period. Unfortunately, the time was longer in our study than in others. An analysis conducted in Lower Silesia between 2016 and 2018 found the mean time from first symptoms to diagnosis to be 5.8 ± 8.0 months [38] and the median time to be 4.0 ± 6.3 months in the neighboring Czech Republic in the period 2002 - 2017 [17].

In our study, no significant differences were found between CD and UC with regard to the period of onset and diagnosis. Usually, a longer time is observed for CD than UC, which may be connected with the less-specific symptoms presented by CD patients and a delay in reporting them; however, such results were only noted in the second studied period. Also, no difference in time between the first symptoms and diagnosis was recorded with regard to place of residence, suggesting that it does not play a significant role.

There have been little data reported on seasonal variations in the onset of IBD in children. Moreover, global data regarding the seasonality of IBD are conflicting. Dharmaraj et al suggested that the onset of IBD has a seasonal trend with the highest incidence in the fall and the lowest in the summer [41]. In contrast, Aratari et al showed that the onset of symptoms was more common in spring and summer [42]. Based on Araki et al, no seasonal variations in disease onset in UC patients were shown [5], but similarly to Aratari et al [42], CD onset was significantly more frequent in summer. Some other reports revealed no seasonality in disease onset [38, 43]. In our present analysis, no particular season was found to have a significantly greater risk of developing IBD; however, the highest number of IBD cases, including UC and CD, occurred in autumn. Moreover, it is interesting that in our study, similarly to others [5, 41], the onset of disease in CD patients was more frequent in summer. There are no findings that clearly explain the underlying mechanisms related to the seasonality of IBD. The following may be of importance: viruses (generally more common in autumn and winter), bacteria (e.g., Campylobacter peak in late summer and fall), antibiotics and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (which are used more frequently during these seasons), climate, hours of sunlight, and food which might affect the differences in disease onset. All these factors can result in microbiota alterations, intestinal mucosal damage, and impact on the activity of the immune system, which may be involved in the pathogenesis of IBD. It is emphasized that environmental factors are associated with onset of IBD. Tani et al showed that oral commensals Actinomyces and its symbiont TM7-3 were correlatively fluctuated in the feces of CD patients by season [44].

Comparison of the incidence of new IBD cases, in the present study, including CD, showed some decline in spring and summer in the period 2017 - 2022. It is difficult to say what contribution COVID-19 infection had to this observation. It is assumed that any virus, including SARS-CoV-2, may serve as a catalyst for the onset of IBD in individuals who are genetically predisposed to develop the illness [45]. The unexpected decline in the frequency of new cases in spring and summer in the period 2017 - 2022 probably may be explained by home isolation due to COVID-19 pandemic.

A multicenter study conducted in Argentina established a diagnosis of IBD in 52% of boys in 2012 - 2013 [46], which is comparable to our present findings. Similar to an analysis conducted in Saxony (Germany) over a 15-year period (2000 - 2014) among 532 IBD patients, under 15 years old, 312 (58.6%) were male and 220 (41.4%) were female [37]. Also, in a previously mentioned single-center Croatian study, boys dominated and constituted 60.7% of patients [30]. According to a study based on aggregated data by Long et al, the IBD incidence was slightly higher in boys [28]. In CD, the prepubertal prevalence is slightly higher in males (1.5:1), whereas in adults, the prevalence is slightly higher in females [47]. The increased prevalence and the shift in sex dominance observed during this period may be attributable to changes in sex hormones during adolescence. Clinical data confirm that sex hormones play a modulatory role of toward intestinal mucosal barrier, immune function, and gut microbiota [47].

Our estimates according to genetic background are in line with global data indicating that between 5% and 23% of patients have a first-degree relative with IBD, and the risk is greater among those whose mother is affected [1]. The first-degree relatives of CD patients have an eight-fold higher risk of developing IBD, while those of UC patients have an approximately four-fold higher risk [48]. Although our study did not show a statistically significant difference between IBD types and IBD inheritance, the CD diagnoses were dominant.

A number of Danish studies have noted an increasing trend in the number of patients receiving biological therapy [49]. Also, a Polish study found that biological treatment was used more frequently from 2012 to 2020, with it being most commonly used in patients aged 10 to 19 years [50]. Puzzlingly, our present data indicate that in the period 2011 to 2016, a higher proportion of patients required biological treatment relative to the total number of diagnoses during this time, while two more people received biological treatment during the second period (2017 to 2022). Our present findings differ from those of other studies in this regard. This may be explained by the small number of patients examined, the specificity of the population in this geographical location, or the short observation period. Although proportionally more patients were treated biologically in the first period, the number of patients with IBD in the second period was significantly higher. It is possible that the children from the second study period received biological treatment later, i.e. after the end of the study.

Living in an urban environment is known to be associated with an increased risk of developing IBD, especially for children. This may be due to being in close contact with higher pollution levels, increased consumption or processed and packaged foods, and increasing urbanization accompanying socioeconomic development, which can affect the microbiome in susceptible individuals. A meta-analysis based on 40 studies showed a positive association between IBD and urban living [51]. Additionally, a Canadian study indicated that children living in the first 5 years of life in a rural area have a lower risk of IBD [52]. In a similar study to ours, conducted in the other district of Poland, i.e. Lower Silesia, the IBD diagnoses dominated among the urban population. There was no significant difference in the incidence of CD/UC taking into account the place of living [38]. Indeed, our present data also indicate a higher risk of all studied IBD children among urban residents, regardless of the type of IBD. This is probably due to the different environmental conditions of children living in urban and rural areas, which is consistent with the hypotheses concerning the etiology of IBD.

The present study is the first to describe the incidence of IBD in the central-northern district of Poland according to a longitudinal data set. In line with other studies, our findings confirm a growing trend of IBD in the pediatric population. As such, there is a need for further analysis of potential, modifiable, environmental factors that may increase the risk of IBD, which may open the way to establishing prophylactic approaches and new, more effective and less burdensome treatment methods, which is especially important in young children. It is worth emphasizing that the child’s disease leads to many consequences, e.g. impairment of growth and development, school absenteeism, withdrawal of extracurricular activities, and therapy adherence. The decreasing age of onset of IBD highlights the need to improve the rules of management and care for children with IBD.

Our findings suggest that medical facilities, including our region, should prepare for the possibility of providing medical care for increasing numbers of patients with IBD, and should take into account the climbing costs of therapy and chronic, multi-directional, specialized care [53]. Moreover, our research results indicate the necessity of efficient training of healthcare employees (especially specialists involved in the treatment of these children), increasing places in pediatric hospitals, streamlining the process of admitting these children to outpatient clinics, planning the increase in treatment costs, improving public awareness, unifying procedures for dealing with patients with IBD, especially in the face of large migration movements, and implementing new methods of diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. As a result, this may contribute to improving the quality of life of patients and their families.

We strongly believe that our data will be useful for planning and shaping the health policy, and that they will expand worldwide database.

However, the study also has its limitations. It includes a relatively small number of patients, and data were acquired from only one center. We are aware that the study was conducted in the particular district of Poland and the results may not reflect the whole country. Although one center does not allow generalization of results to the entire population, usually children from Kujawsko-Pomorskie Voivodeship are referred to our center to determine or confirm the diagnosis and start the treatment. Individual cases of IBD may have been diagnosed outside our center, but probably, the number of such children was small and did not have an impact on our results. The analysis conducted is particularly important for our region, although it seems that taking into account the Polish population and similar environmental conditions, generalization of our research results is not a major error, although a multicenter study would certainly give bigger sample and more reliable results.

The next limitation is the retrospective design, which is at high risk for many research biases. They are particularly at risk for recall bias and observer bias due to their reliance on memory and self-reported data. To avoid a significant bias in the results, similar to German study [37], we took into account the final diagnosis, not the initial one (thus, we excluded misdiagnosed patients) and patients with 100% correctly completed questionnaire. In contrast with a Canadian study [51], we did not analyze incorrectly classified and diagnosed cases, because we diagnosed patients based on the same criteria throughout the entire study period.

Another limitation is that disease severity was only indicated by the adoption of biological treatment. To address these shortcomings, we plan to conduct a similar study based on a broader population from multiple centers using a prospective approach.

Despite the single-center nature of the study, the strength of the study is supporting the research results over 10 years of children (patients under 18 years of age) registry and comparison with a lot of studies. Difficulty in comparing data may also result from other definitions of the child population, e.g. Kuenzing et al studied patients under 21 years old [31] and Larrosa-Haro et al from Argentina included patients from 2 to 16 years of age [34].

IBD will continue to be an important public health problem with extensive healthcare and economic costs in the future. The reported IBD burden in children and adolescents at the global, regional, and national levels will inform policymakers and help them formulate locally adapted health policies.

Additionally, any attempt to understand the growing prevalence of IBD may play a significant role in establishing new methods for its prevention and treatment to improve the quality of life of patients and their families.

Conclusions

The incidence of PIBD in central-northern district of Poland is rather low compared to other countries. However, it appears to be increasing, particularly in children with UC, the number of IBD diagnoses in children has increased by nearly 50% over the last 6 years. There is a need to better understanding the causes of this growing trend, as this is key to developing new methods of prevention and treatment.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Informed Consent

All patients’ parents gave their written informed consent to take part in the study.

Author Contributions

JWR was the corresponding author. JWR and AK: study conception, data collection, statistical analysis, figures design, wrote and revised the manuscript.

Data Availability

Any inquiries regarding supporting data availability of this study should be directed to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

CD: Crohn’s disease; ESPGHAN: The European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; IBD-U: unclassified inflammatory bowel disease; ICD-10 codes: International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision; M: mean value; Max: maximum; Min: minimum; N: number of cases; NFZ: National Health Fund; PIBD: pediatric inflammatory bowel disease; PIN: personal identification number; SD: standard deviation; UC: ulcerative colitis; VEO-IBD: very early-onset IBD

| References | ▴Top |

- Borowitz SM. The epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: clues to pathogenesis? Front Pediatr. 2022;10:1103713.

doi pubmed - Levine A, Koletzko S, Turner D, Escher JC, Cucchiara S, de Ridder L, Kolho KL, et al. ESPGHAN revised porto criteria for the diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;58(6):795-806.

doi pubmed - Rosen MJ, Dhawan A, Saeed SA. Inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(11):1053-1060.

doi pubmed - McDowell C, Farooq U, Haseeb M. Inflammatory bowel disease. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL) with ineligible companies. 2025.

pubmed - Araki M, Shinzaki S, Yamada T, Arimitsu S, Komori M, Shibukawa N, Mukai A, et al. Age at onset is associated with the seasonal pattern of onset and exacerbation in inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol. 2017;52(11):1149-1157.

doi pubmed - Carreras-Torres R, Ibanez-Sanz G, Obon-Santacana M, Duell EJ, Moreno V. Identifying environmental risk factors for inflammatory bowel diseases: a Mendelian randomization study. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):19273.

doi pubmed - Zhao M, Gonczi L, Lakatos PL, Burisch J. The burden of inflammatory bowel disease in Europe in 2020. J Crohns Colitis. 2021;15(9):1573-1587.

doi pubmed - Zhang L, Agrawal M, Ng SC, Jess T. Early-life exposures and the microbiome: implications for IBD prevention. Gut. 2024;73(3):541-549.

doi pubmed - Dolinska A, Wasielewska Z, Krogulska A. [Early risk factors for the development of inflammatory bowel disease in the pediatric population of the Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship]. Dev Period Med. 2018;22(4):341-350.

doi pubmed - Mrowicki J, Mrowicka M, Majsterek I. [Environmental factors increasing the risk of activation and development of inflammatory bowel diseases]. Postepy Biochem. 2020;66(2):167-175.

doi pubmed - Cui G, Yuan A. A systematic review of epidemiology and risk factors associated with Chinese inflammatory bowel disease. Front Med (Lausanne). 2018;5:183.

doi pubmed - Lavelle A, Sokol H. Gut microbiota-derived metabolites as key actors in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17(4):223-237.

doi pubmed - Conlon MA, Bird AR. The impact of diet and lifestyle on gut microbiota and human health. Nutrients. 2014;7(1):17-44.

doi pubmed - Kaplan GG, Bernstein CN, Coward S, Bitton A, Murthy SK, Nguyen GC, Lee K, et al. The impact of inflammatory bowel disease in Canada 2018: epidemiology. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol. 2019;2(Suppl 1):S6-S16.

doi pubmed - Kaplan GG, Windsor JW. The four epidemiological stages in the global evolution of inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18(1):56-66.

doi pubmed - Bendix M, Dige A, Jorgensen SP, Dahlerup JF, Bibby BM, Deleuran B, Agnholt J. Seven weeks of high-dose vitamin D treatment reduces the need for infliximab dose-escalation and decreases inflammatory markers in Crohn's disease during one-year follow-up. Nutrients. 2021;13(4):1-11.

doi pubmed - Jabandziev P, Pinkasova T, Kunovsky L, Papez J, Jouza M, Karlinova B, Novackova M, et al. Regional incidence of inflammatory bowel disease in a Czech Pediatric population: 16 years of experience (2002-2017). J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2020;70(5):586-592.

doi pubmed - Sykora J, Pomahacova R, Kreslova M, Cvalinova D, Stych P, Schwarz J. Current global trends in the incidence of pediatric-onset inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24(25):2741-2763.

doi pubmed - Rajasekaran V, Evans HM, Andrews A, Bishop JR, Lopez RN, Mouat S, Han DY, et al. Rising incidence of inflammatory bowel disease in South Asian Children in New Zealand-a retrospective population-based study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2023;76(6):749-755.

doi pubmed - Forbes AJ, Frampton CMA, Day AS, Vernon-Roberts A, Gearry RB. Descriptive epidemiology of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease in Oceania: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2023;77(4):512-518.

doi pubmed - Benchimol EI, Mack DR, Nguyen GC, Snapper SB, Li W, Mojaverian N, Quach P, et al. Incidence, outcomes, and health services burden of very early onset inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2014;147(4):803-813 e807; quiz e814-805.

doi pubmed - Lewis JD, Parlett LE, Jonsson Funk ML, Brensinger C, Pate V, Wu Q, Dawwas GK, et al. Incidence, prevalence, and racial and ethnic distribution of inflammatory bowel disease in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2023;165(5):1197-1205.e1192.

doi pubmed - Blumenstein I, Sonnenberg E. Sex- and gender-related differences in inflammatory bowel diseases. Front Gastroenterol. 2023;2:1-9.

- Zagorowicz E, Walkiewicz D, Kucha P, Perwieniec J, Maluchnik M, Wieszczy P, Regula J. Nationwide data on epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in Poland between 2009 and 2020. Pol Arch Intern Med. 2022;132(5):16194.

doi pubmed - Turner D, Ruemmele FM, Orlanski-Meyer E, Griffiths AM, de Carpi JM, Bronsky J, Veres G, et al. Management of paediatric ulcerative colitis, part 1: ambulatory care-an evidence-based guideline from European Crohn's and Colitis Organization and European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018;67(2):257-291.

doi pubmed - Levine A, Griffiths A, Markowitz J, Wilson DC, Turner D, Russell RK, Fell J, et al. Pediatric modification of the Montreal classification for inflammatory bowel disease: the Paris classification. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17(6):1314-1321.

doi pubmed - Karolewska-Bochenek K, Lazowska-Przeorek I, Albrecht P, Grzybowska K, Ryzko J, Szamotulska K, Radzikowski A, et al. Epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease among children in Poland. A prospective, population-based, 2-year study, 2002-2004. Digestion. 2009;79(2):121-129.

doi pubmed - Long D, Wang C, Huang Y, Mao C, Xu Y, Zhu Y. Changing epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2024;39(1):73.

doi pubmed - Ivkovic L, Hojsak I, Trivic I, Sila S, Hrabac P, Konjik V, Senecic-Cala I, et al. Incidence and geographical variability of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease in Croatia: data from the Croatian National Registry for children with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2020;59(13):1182-1190.

doi pubmed - Pivac I, Jelicic Kadic A, Despot R, Zitko V, Tudor D, Runjic E, Markic J. Characteristics of the inflammatory bowel disease in children: a Croatian single-centre retrospective study. Children (Basel). 2023;10(10):1677.

doi pubmed - Kuenzig ME, Fung SG, Marderfeld L, Mak JWY, Kaplan GG, Ng SC, Wilson DC, et al. Twenty-first century trends in the global epidemiology of pediatric-onset inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(4):1147-1159.e1144.

doi pubmed - Ye Y, Manne S, Treem WR, Bennett D. Prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in pediatric and adult populations: recent estimates from large national databases in the United States, 2007-2016. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26(4):619-625.

doi pubmed - Arcucci MS, Contreras MB, Gallo J, Antoniska MA, Busoni V, Tennina C, D'Agostino D, et al. Pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: a multicenter study of changing trends in argentina over the past 30 years. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2022;25(3):218-227.

doi pubmed - Larrosa-Haro A, Abundis-Castro L, Contreras MB, Gallo MJ, Pena-Quintana L, Targa Ferreira CH, Nacif PA, et al. Epidemiologic trend of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease in Latin America: The Latin American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (LASPGHAN) Working Group. Rev Gastroenterol Mex (Engl Ed). 2021;86(4):328-334.

doi pubmed - Choe JY, Choi S, Song KH, Jang HJ, Choi KH, Yi DY, Hong SJ, et al. Incidence and prevalence trends of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease in the Daegu-Kyungpook Province from 2017 to 2020. Front Pediatr. 2021;9:810173.

doi pubmed - Virta LJ, Saarinen MM, Kolho KL. Inflammatory bowel disease incidence is on the continuous rise among all paediatric patients except for the very young: a nationwide registry-based study on 28-year follow-up. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11(2):150-156.

doi pubmed - Kern I, Schoffer O, Richter T, Kiess W, Flemming G, Winkler U, Quietzsch J, et al. Current and projected incidence trends of pediatric-onset inflammatory bowel disease in Germany based on the Saxon Pediatric IBD Registry 2000-2014 -a 15-year evaluation of trends. PLoS One. 2022;17(9):e0274117.

doi pubmed - Krzesiek E, Kofla-Dlubacz A, Akutko K, Stawarski A. The incidence of inflammatory bowel disease in the paediatric population in the District of Lower Silesia, Poland. J Clin Med. 2021;10(17):3994.

doi pubmed - Ashton JJ, Barakat FM, Barnes C, Coelho TAF, Batra A, Afzal NA, Beattie RM. Incidence and prevalence of paediatric inflammatory bowel disease continues to increase in the South of England. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2022;75(2):e20-e24.

doi pubmed - Henderson P, Hansen R, Cameron FL, Gerasimidis K, Rogers P, Bisset WM, Reynish EL, et al. Rising incidence of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease in Scotland. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18(6):999-1005.

doi pubmed - Dharmaraj R, Jaber A, Arora R, Hagglund K, Lyons H. Seasonal variations in onset and exacerbation of inflammatory bowel diseases in children. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:696.

doi pubmed - Aratari A, Papi C, Galletti B, Angelucci E, Viscido A, D'Ovidio V, Ciaco A, et al. Seasonal variations in onset of symptoms in Crohn's disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2006;38(5):319-323.

doi pubmed - Romberg-Camps MJ, Hesselink-van de Kruijs MA, Schouten LJ, Dagnelie PC, Limonard CB, Kester AD, Bos LP, et al. Inflammatory Bowel Disease in South Limburg (the Netherlands) 1991-2002: Incidence, diagnostic delay, and seasonal variations in onset of symptoms. J Crohns Colitis. 2009;3(2):115-124.

doi pubmed - Tani M, Shinzaki S, Asakura A, Tashiro T, Amano T, Otake-Kasamoto Y, Yoshihara T, et al. Seasonal variations in gut microbiota and disease course in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. PLoS One. 2023;18(4):e0283880.

doi pubmed - Corrias A, Cortes GM, Bardanzellu F, Melis A, Fanos V, Marcialis MA. Risk, course, and effect of SARS-CoV-2 infection in children and adults with chronic inflammatory bowel diseases. Children (Basel). 2021;8(9):753.

doi pubmed - Vicentin R, Wagener M, Pais AB, Contreras M, Orsi M. One-year prospective registry of inflammatory bowel disease in the Argentine pediatric population. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2017;115(6):533-540.

doi pubmed - Rustgi SD, Kayal M, Shah SC. Sex-based differences in inflammatory bowel diseases: a review. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2020;13:1756284820915043.

doi pubmed - El Hadad J, Schreiner P, Vavricka SR, Greuter T. The genetics of inflammatory bowel disease. Mol Diagn Ther. 2024;28(1):27-35.

doi pubmed - Wewer MD, Arp L, Sarikaya M, Felding OK, Vind I, Pedersen G, Mertz-Nielsen A, et al. The use and efficacy of biological therapies for inflammatory bowel disease in a Danish Tertiary Centre 2010-2020. Crohns Colitis 360. 2022;4(4):otac041.

doi pubmed - Kucha P, Zagorowicz E, Walkiewicz D, Perwieniec J, Maluchnik M, Wieszczy P, Regula J. Biologic treatment of inflammatory bowel disease in Poland, 2012-2020: nationwide data. Pol Arch Intern Med. 2022;132(7-8):16287.

doi pubmed - Benchimol EI, Kaplan GG, Otley AR, Nguyen GC, Underwood FE, Guttmann A, Jones JL, et al. Rural and urban residence during early life is associated with risk of inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based inception and birth cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(9):1412-1422.

doi pubmed - Soon IS, Molodecky NA, Rabi DM, Ghali WA, Barkema HW, Kaplan GG. The relationship between urban environment and the inflammatory bowel diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:51.

doi pubmed - Kumar A, Yassin N, Marley A, Bellato V, Foppa C, Pellino G, Myrelid P, et al. Crossing barriers: the burden of inflammatory bowel disease across Western Europe. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2023;16:17562848231218615.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Gastroenterology Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.