| Gastroenterology Research, ISSN 1918-2805 print, 1918-2813 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, Gastroenterol Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://gr.elmerpub.com |

Short Communication

Volume 18, Number 5, October 2025, pages 262-268

Characterizing Patterns of Care for Diverticulitis Within the Contemporary Health System

Hyung C. Kima, e, Vikram Anandb, c, Jennifer A. Kaplana, c, d, Ravi Moonkaa, c, d, Vlad V. Simianua, c, d

aDepartment of General Surgery, Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle, WA, USA

bDepartment of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle, WA, USA

cCenter for Digestive Health, Virginia Mason Franciscan Health, Seattle, WA, USA

dSection of Colorectal Surgery, Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle, WA, USA

eCorresponding Author: Hyung C. Kim, Department of General Surgery, Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle, WA 98101, USA

Manuscript submitted June 13, 2025, accepted August 11, 2025, published online October 9, 2025

Short title: Contemporary Care Patterns for Diverticulitis

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/gr2055

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Diverticulitis is a common colon pathology that contributes a significant healthcare burden due to hospitalizations, colonoscopies, and operations. Although recent clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) advocate for less frequent and selective use of antibiotics, colonoscopies, admissions, and operations, rates of admissions and elective operations for diverticulitis have paradoxically increased over time. Understanding where patients seek care for diverticulitis can identify areas where CPGs are or are not being followed. This study aimed to describe care settings, treating providers, and characterize treatment patterns for diverticulitis.

Methods: This prospective cohort study included patients with diverticulitis diagnosed via computed tomography (CT) scan at a single institution between 2019 and 2020. The CT scan setting (outpatient, emergency department, or inpatient), main treating provider specialty (medicine, surgery, gastroenterology, or emergency medicine), and clinical characteristics were identified. For each patient, antibiotic prescription, screening colonoscopy within a year of diagnosis, and surgical referrals were characterized.

Results: A total of 310 patients (mean age 62, 60.3% female) were included, with 71.3% being new diagnoses of diverticulitis. Eighteen percent of diagnoses were complicated diverticulitis. Most diagnoses occurred in the outpatient setting (60%), followed by the emergency department (36.5%), then inpatient (3.5%). Complicated diverticulitis cases more frequently presented to the emergency department than outpatient (25% vs. 12.9%, P = 0.002). Antibiotics were prescribed in 91% of cases, with the highest rate in the emergency department (96.5%) compared to outpatient (87.6%) or inpatient (90.9%, P = 0.036). Colonoscopy was up to date in 45.1% of uncomplicated and 54.4% of complicated cases (P = 0.137). Surgical referrals occurred in 38.7% of patients, with higher rates for complicated diverticulitis (84.2% vs. 28.6%, P < 0.001).

Conclusion: Most episodes of diverticulitis are uncomplicated and occur in the outpatient setting. However, care remains fragmented across multiple specialties, making it challenging to measure the appropriate delivery of CPG-concordant care for diverticulitis. The variation in management of diverticulitis highlights the need for a more coordinated, system-level approach to enable high-quality care delivery.

Keywords: Diverticulitis; Colonoscopy; Antibiotics; Clinical practice guideline; Colorectal surgery; Gastroenterology

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Diverticulitis of the colon is one of the most common benign colonic pathologies, accounting for over 1.4 million outpatient visits and 300,000 inpatient admissions annually in the United States [1, 2]. Beyond its estimated 2 billion dollar annual cost to the healthcare system [1], diverticulitis also imposes a substantial personal burden on patients - and the problem is growing. Prevalence of diverticulitis continues to increase [3], and medical and surgical management guidelines for diverticulitis have also evolved to recommend a more outpatient and less interventional approach to diverticulitis. Despite updated guidelines recommending more selective use of antibiotics, colonoscopy, and surgery for diverticulitis, population-level data show that rates of hospital admission and elective operations for diverticulitis have increased over time [3, 4].

Although we do not directly evaluate admission or surgery rates in this study, this broader trend highlights a potential disconnect between guidelines and real-world practice. To explore this gap, we focus on three key aspects of diverticulitis management - antibiotics, updated colonoscopy, and surgical referral - as practical and measurable proxies for guideline-concordant care. By evaluating these metrics, we aim to identify gaps and opportunities for improvement.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

This study was deemed minimal risk by the Benaroya Research Institute Institutional Review Board at Virginia Mason Medical Center. We prospectively captured all patients who had diverticulitis diagnosed on computed tomography (CT) scan at Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle, USA, between 2019 and 2020. All CT scans were interpreted by board-certified radiologists. Radiologists were not aware of the study at the time of interpretation. Each week, patients with “diverticulitis” reported on their CT scans were prospectively identified and the patients’ demographics and clinical characteristics of diverticulitis were reviewed from their patient charts and recorded in a secure database. These characteristics included whether the diverticulitis was complicated (fistula, perforation, stricture, or abscess) or uncomplicated, whether it was a new or recurrent episode, and the setting in which the CT scan was performed (outpatient, inpatient, or emergency department (ED)). Then, patients were categorized by treatment setting (outpatient, inpatient, or ED) and the specialty of the managing physician. This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the Institutional Review Board.

In the outpatient setting, managing specialties were categorized as medicine (including primary care, urgent care, and non-gastroenterology medical subspecialties), surgery, or gastroenterology. If the patient was evaluated in the ED and discharged, the managing specialty was classified as emergency medicine (EM). In the inpatient setting, managing specialties included medicine, surgery, and gastroenterology. If the patient was admitted to the hospitalist service without consulting services, the managing specialty was classified as medicine. However, if another specialty either admitted the patient or was consulted specifically for management of diverticulitis, then they were categorized according to the managing specialty.

Subgroup analysis was conducted based on the treatment setting, focusing on patient age, sex, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), signs of sepsis at presentation, and immunocompromised status. Sepsis criteria were derived from disease severity definitions outlined in clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) from multiple professional societies and included fevers, chills, refractory symptoms or vomiting, C-reactive protein (CRP) > 140 mg/L, or white blood cell count > 15 × 109 cells/L [5-7]. Patients were further analyzed with a focus on three aspects of care for diverticulitis: antibiotic prescription, updated colonoscopy within 1 year before or after diagnosis of diverticulitis, and whether the patient ultimately received a surgical referral to see a surgeon about management for diverticulitis. Categorical variables were compared using Pearson’s χ2 test. Continuous variables were compared using t-tests, analysis of variance (ANOVA), or Mann-Whitney U tests. Statistical significance was assigned a P-value of < 0.05. Sankey diagrams were generated using SankeyMATIC, a free online tool that facilitates visual representation of flows between variables [8].

| Results | ▴Top |

From 2019 to 2020, 310 patients (mean age 62 ± 13.2, 60.3% female) had diverticulitis diagnosed on CT scan. Of the cohort, 221 (71.3%) patients had new diagnoses of diverticulitis, and 57 (18.4%) patients had complicated diverticulitis. Out of the 310 patients, 186 (60%) were diagnosed in the outpatient setting, 113 (36.5%) in the ED, and 11 (3.5%) in the inpatient setting. Complicated diverticulitis was more likely to present to the ED than outpatient (n = 28 (25%) vs. n = 24 (12.9%), P = 0.002). Of the 253 patients with uncomplicated diverticulitis, 157 (62.1%) were treated in the outpatient setting, 77 (30.4%) in the ED, and 19 (7.5%) in the inpatient setting. Among the 57 patients with complicated diverticulitis, 17 (29.8%) were treated as outpatients, one (1.8%) in the ED, and 39 (68.4%) in the inpatient setting.

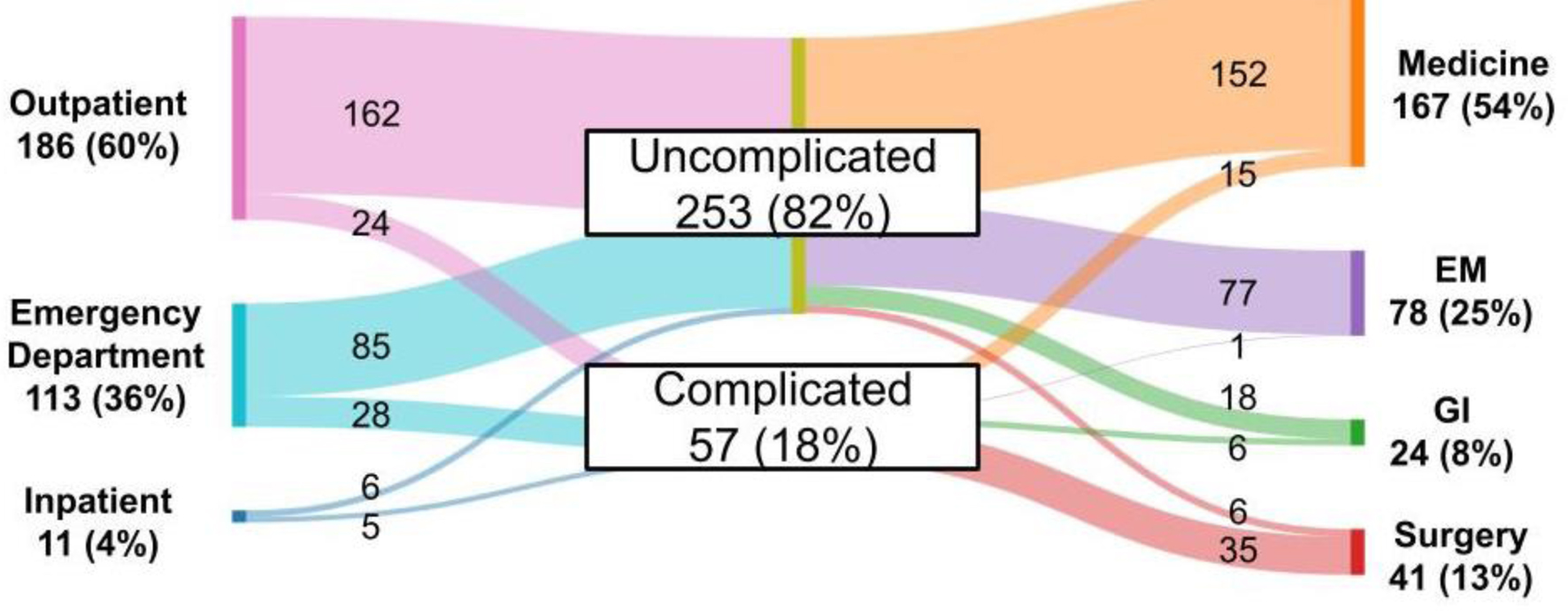

Subgroup analysis on treatment setting revealed differences in age, CCI, signs of sepsis at presentation, but not in sex or immunocompromised status (Table 1). Specifically, patients treated in the inpatient setting were older (mean age 67 vs. 61 in outpatient or 59 in ED, P < 0.01), and were more frequently septic (36.2% inpatient vs. 9.8% outpatient or 14.1% ED, P < 0.01) compared to those treated outpatient or at the ED. Patients with CCI 3 or higher were treated in the outpatient setting more frequently than inpatient (38% vs. 20%, P = 0.03), but not ED (38% vs. 29%, P = 0.17). The majority were managed by medicine (167 patients (53.9%)), while 78 (25.2%) were managed by EM, 41 (13.2%) by surgery, and 24 (7.7%) by gastroenterology, across various settings (Fig. 1).

Click to view | Table 1. Subgroup Analysis Based on the Treatment Setting |

Click for large image | Figure 1. Relationship of CT setting, characterization of diverticulitis, and treating provider specialty. CT: computed tomography. |

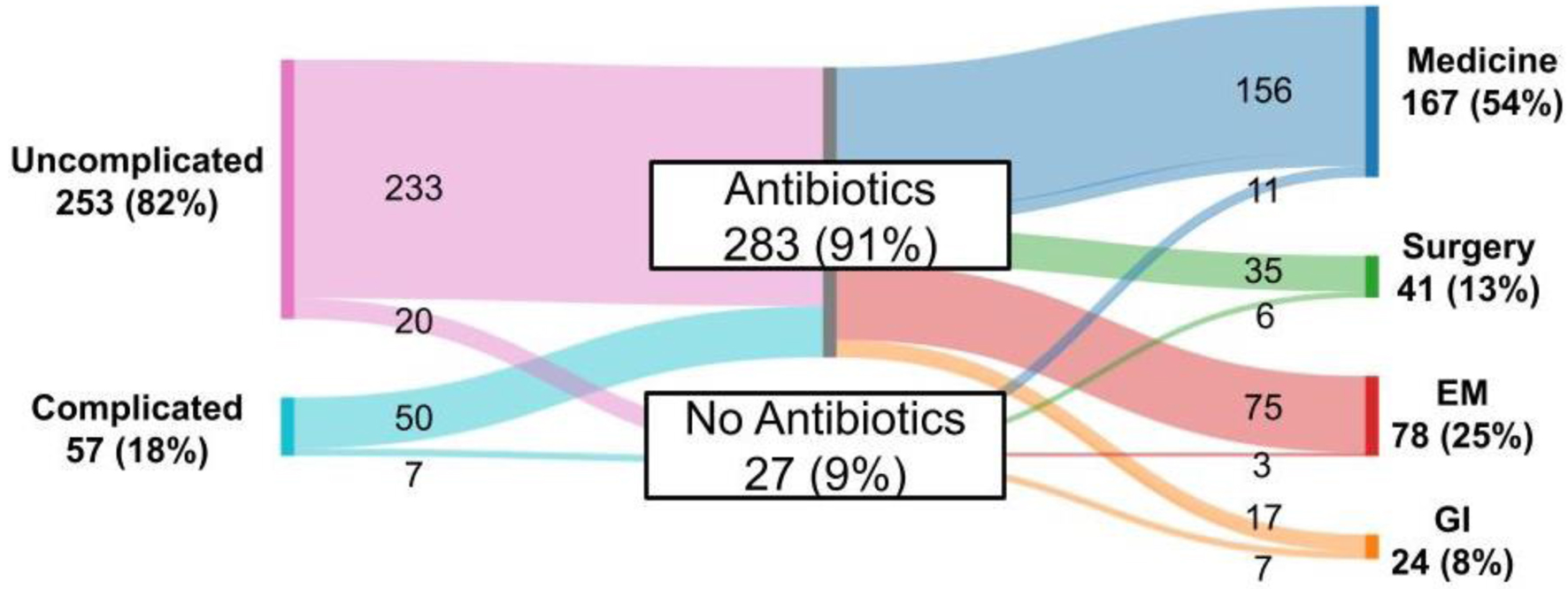

A total of 283 (91.3%) patients received antibiotics (Fig. 2). Among those with uncomplicated diverticulitis, 233 (92.1%) patients were treated with antibiotics - 140 (60%) received oral and 93 (39.9%) received intravenous antibiotics. In the complicated diverticulitis group, 50 (87.7%) patients received antibiotics, with 11 (22%) being treated orally and 39 (78%) being treated intravenously. Furthermore, a subgroup of 135 patients (88 treated in the outpatient setting, 45 in the ED, and two as inpatients) with uncomplicated diverticulitis had no signs of sepsis, a CCI less than 3, and were not immunocompromised, representing a healthier, non-septic, immunocompetent patient population. Among this group, 126 (93.3%) patients received antibiotics. The overall highest rate of antibiotic prescription was in the ED (96.5%) compared to outpatient (87.6%) or inpatient setting (90.9%, P = 0.036).

Click for large image | Figure 2. Pattern of antibiotic prescription by treating provider specialty. |

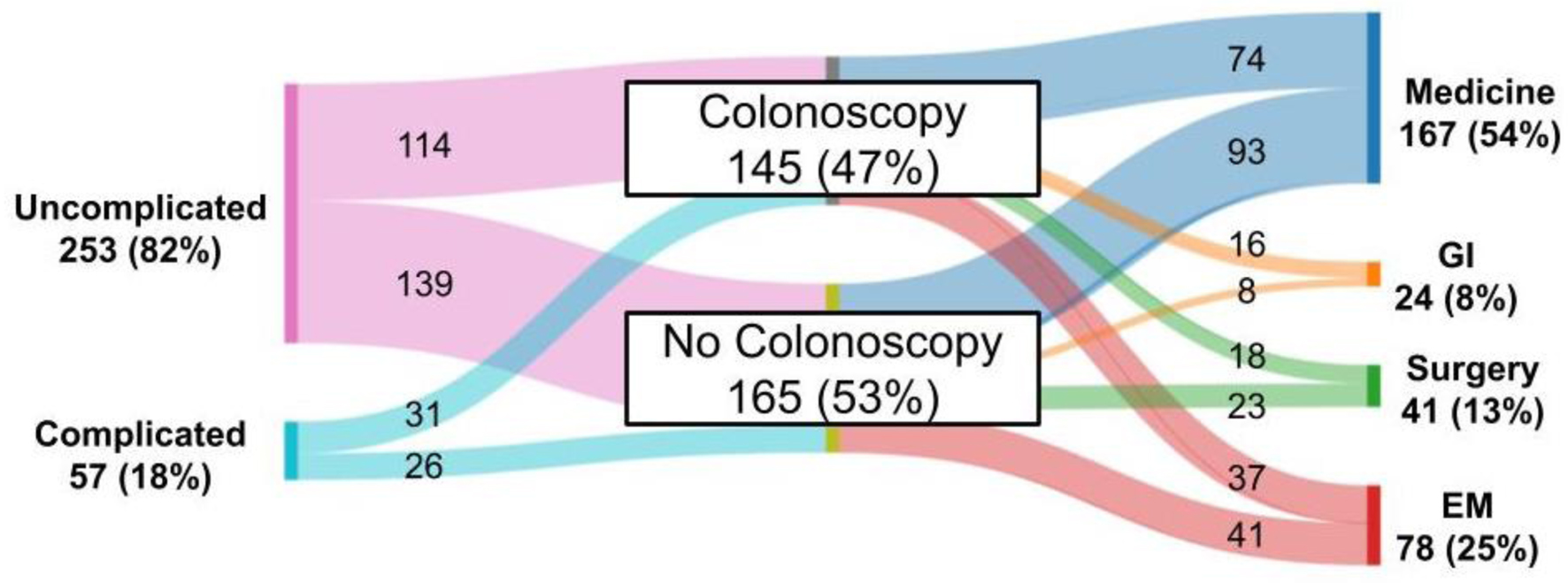

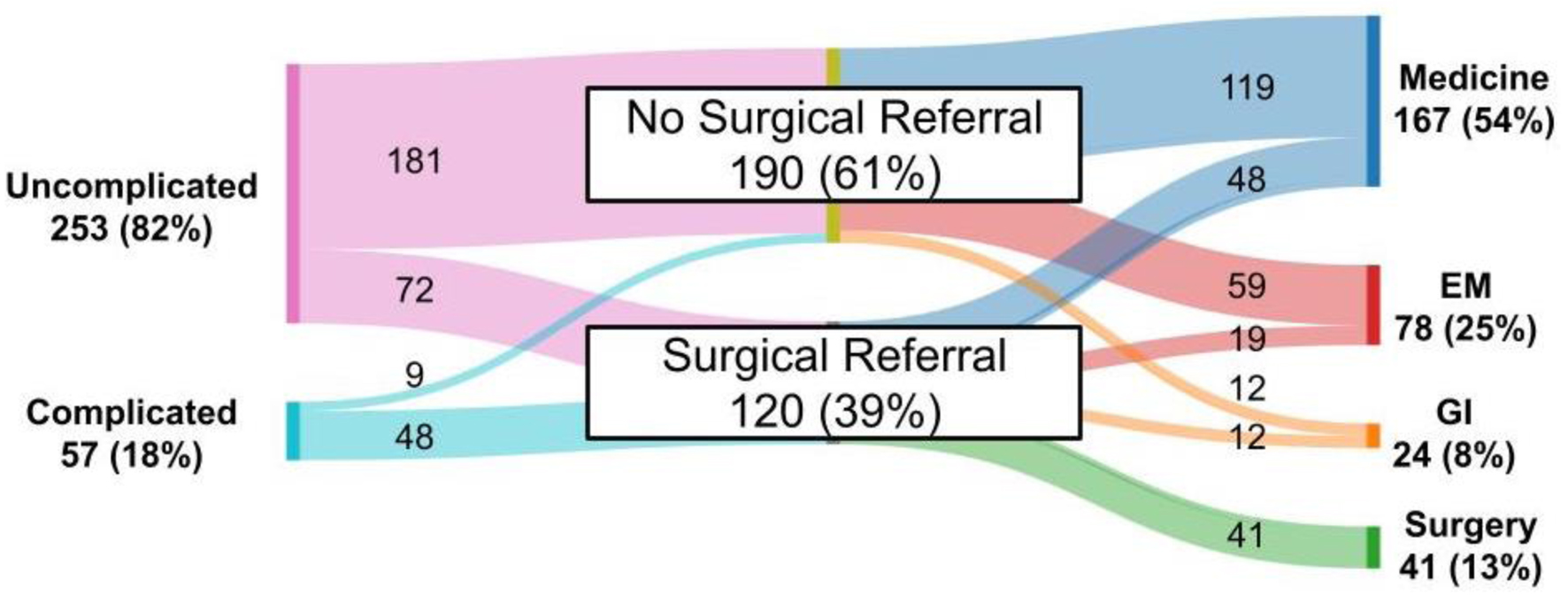

Up-to-date colonoscopy within 1 year of diagnosis was documented in 145 (46.8%) patients (Fig. 3), and there was no statistically significant difference between rates of up-to-date colonoscopy in uncomplicated versus complicated diverticulitis (45.1% vs. 54.4%, P = 0.137). In the outpatient setting, patients with diverticulitis managed by gastroenterology were most likely to be up to date on their colonoscopy (77.78% vs. 43.8% medicine or 71.4% surgery, P < 0.01), but not in other settings. Surgical consultation regarding management of diverticulitis was obtained in 120 (38.7%) patients (Fig. 4), with complicated diverticulitis patients more likely to be seen by a surgeon than patients with uncomplicated diverticulitis (84.2% vs. 28.5%, P < 0.001). All surgical referrals were from other providers (i.e., primary care providers, EM providers, or specialists). Of the 120 patients who met with a surgeon, 59 (49.2%) ultimately underwent surgery for diverticulitis, with surgery being more frequent in the complicated diverticulitis patients, 27 (47% of complicated), than the 32 (13% of uncomplicated) uncomplicated diverticulitis patients. Overall, three patients had emergent surgeries (two patients with peritonitis due to perforation, one patient with large bowel obstruction).

Click for large image | Figure 3. Pattern of colonoscopy referral by treating provider specialty. |

Click for large image | Figure 4. Pattern of surgical referral by treating provider specialty. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Multiple guidelines from both medical and surgical societies offer recommendations for the management of diverticulitis (Table 2) [5-7, 9-12]. Focusing on three key aspects of care, antibiotic prescription, colonoscopy, and surgical intervention, the general consensus is that: 1) selective immunocompetent patients with uncomplicated diverticulitis can be managed with supportive care alone without antibiotics; 2) updated colonoscopy is recommended following an episode of complicated diverticulitis; and 3) decisions regarding surgery should be individualized, rather than based on specific number of episodes or patient age.

Click to view | Table 2. Medical and Surgical Society Guidelines for Management of Diverticulitis |

In this study, 93.3% of non-septic, immunocompetent patients with uncomplicated diverticulitis and without significant comorbidities were prescribed antibiotics - a rate that is high given that current guidelines recommend supportive care alone without antibiotics in immunocompetent and non-septic patients, as well as in comparison to the rate of antibiotic prescription reported in the literature (19-58.9%) [13, 14]. Additionally, only 54.4% of patients with complicated diverticulitis had an updated colonoscopy within 1 year before or after diagnosis of diverticulitis, which is low given the current best practice recommendations on the basis of higher observed risk of adenoma and cancer detection in patients with complicated diverticulitis [15]. Lastly, 39% of patients had a surgical consultation, and approximately half ultimately underwent surgery. While this does not directly assess the appropriateness of referrals, the observed proportion aligns with existing literature, suggesting that only about 20% of diverticulitis patients undergo operative management [16]. Still, expanding access to surgical and gastroenterology consultations may further help patients better understand the impact of diverticulitis on their quality of life and facilitate shared, informed discussions about operative management.

Unsurprisingly, older patients and those presenting with signs of sepsis were more often managed in the inpatient setting compared to those treated in the outpatient setting or at the ED. This aligns with current clinical practice, as age, frailty, and systemic illness typically prompt closer monitoring and early intervention. Interestingly, however, patients with CCI 3 or higher were more frequently treated as outpatients than inpatients. This finding may reflect that CCI, while a validated tool for predicting long-term mortality risk, is not designed to capture the acute disease-specific factors that influence short-term management decisions for diverticulitis. As such, CCI alone may not be the most appropriate predictor for triage in this context, and incorporating disease-specific severity indices may better guide disposition decisions.

There are a few limitations with this study. First, identification of patterns of care and management was based on chart review, which could miss care outside of this medical record. For instance, we may be misclassifying the number of diverticulitis episodes, updated colonoscopies, or surgical consultations if they occurred outside our institution. Second, this project spanned the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, which could affect all aspects of care, especially follow-up care, hospitalization, and patterns of antibiotic prescriptions. Third, patients with mild, recurrent diverticulitis may have been managed clinically without imaging and thus have been excluded, which in turn could bias our antibiotic use upward as CT-confirmed cases may reflect more definitive or concerning presentations. However, for the purpose of analyzing guideline adherence in documented, confirmed cases, we believe that restricting to CT-diagnosed patients provided a more reliable and reproducible dataset. Lastly, while follow-up colonoscopy within 1 year of diagnosis was used as a proxy for guideline-concordant care, we recognize that this approach does not account for individual patient risk, and some relevant prior colonoscopies may not have been captured within the timeframe reviewed. Colonoscopies performed outside our institution or beyond the 2-year window were not consistently accessible through our electronic medical record, potentially leading to an underestimation of true follow-up rates. This limitation may bias our findings toward underreporting adherence to guidelines. We plan to track these findings longitudinally as a quality measure, and if they remain low, we can potentially link our institutional experience with regional health data or claims databases to improve colonoscopy capture. With these limitations in mind, it might be difficult to definitively conclude if these patients with diverticulitis received guideline-concordant care, but given the unexpectedly high rates of antibiotic prescription and low rates of updated colonoscopies, it seems that there is a meaningful gap in care delivery. Even if true prescription rates were lower and colonoscopy adherence rates were higher, our findings highlight a critical area for system-level improvement in ensuring appropriate management and surveillance.

Despite the above limitations, one particular strength of this cohort is the prospective capture of patients based on CT scans, allowing for detailed assessment of real-world management patterns. The patient demographics and clinical characteristics are consistent with those reported in the literature including gender and age distribution [17] as well as rate of recurrence of about 35% [18]. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine concordance with CPGs in the management of diverticulitis in a disease-based cohort. The findings underscore the challenges of both measuring and achieving guideline-concordant care across diverse settings and specialties taking care of diverticulitis patients.

Several factors likely contribute to this variability. First, guidelines have evolved significantly in recent years, particularly regarding outpatient management and antibiotic use, and providers may not be uniformly aware of or familiar with latest recommendations, especially in specialties for which diverticulitis is not a common focus. While continuing medical education and clinical resources are available at our institution, further efforts, including studies such as this, are needed to enhance awareness and guideline dissemination.

In addition, system-level factors may influence care. Reimbursement structures may favor inpatient management over outpatient treatment, which could inadvertently promote hospitalization or intervention. While specific reimbursement data by setting or specialty were not available for this study, this represents an important area for future investigation. Ideally, as further research and effort go towards this, reimbursement models should align with and support guideline-concordant care, particularly when stratified by disease severity.

Lastly, variation in practice between specialties, including medicine, surgery, gastroenterology, and EM, may also contribute to the observed variability in care, warranting further exploration.

Future efforts at our institution will focus on targeted education, the development of decision support tools, and continuous improvement and feedback. As new technologies such as artificial intelligence and machine learning develop, it may have a role in supporting risk stratification [19] to aid clinicians in decision-making and support guideline-based treatment planning. Another potential strategy is the establishment of a multidisciplinary “diverticulitis home”, where stakeholders from various specialties and care settings can collaborate to promote more consistent, evidence-based management. This proposed model aims to address the variability in care identified in our analysis and could serve as a foundation for future research on further improving the management of diverticulitis.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the support of Benaroya Research Institute in facilitating this research.

Financial Disclosure

This research was supported through an internal pilot grant from Benaroya Research Institute.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare in regards to the publication of this manuscript.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was not obtained, as this study was deemed minimal risk and was exempt from consent requirements by the Institutional Review Board.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: HCK and VVS; methodology: HCK and VVS; data collection: HCK; data analysis: HCK and VVS; writing - original draft: HCK; writing - review and editing: HCK, VA, JAK, RM, and VVS; visualization: HCK; supervision: VVS. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

Any inquiries regarding supporting data availability of this study should be directed to the corresponding author.

| References | ▴Top |

- Klingler MJ, Lipman JM. Acute left-sided colonic diverticulitis: a surgeon's perspective on the ACP guidelines. Cleve Clin J Med. 2023;90(7):403-406.

doi pubmed - Reddy VB, Longo WE. The burden of diverticular disease on patients and healthcare systems. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2013;9(1):21-27.

pubmed - Wheat CL, Strate LL. Trends in hospitalization for diverticulitis and diverticular bleeding in the United States from 2000 to 2010. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(1):96-103.e101.

doi pubmed - Simianu VV, Strate LL, Billingham RP, Fichera A, Steele SR, Thirlby RC, Flum DR. The impact of elective colon resection on rates of emergency surgery for diverticulitis. Ann Surg. 2016;263(1):123-129.

doi pubmed - Peery AF, Shaukat A, Strate LL. AGA clinical practice update on medical management of colonic diverticulitis: expert review. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(3):906-911.e901.

doi pubmed - Bailey J, Dattani S, Jennings A. Diverticular disease: rapid evidence review. Am Fam Physician. 2022;106(2):150-156.

pubmed - Francis NK, Sylla P, Abou-Khalil M, Arolfo S, Berler D, Curtis NJ, Dolejs SC, et al. EAES and SAGES 2018 consensus conference on acute diverticulitis management: evidence-based recommendations for clinical practice. Surg Endosc. 2019;33(9):2726-2741.

doi pubmed - sankeymatic.com.

- Stovall SL, Kaplan JA, Law JK, Flum DR, Simianu VV. Diverticulitis is a population health problem: Lessons and gaps in strategies to implement and improve contemporary care. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2023;15(6):1007-1019.

doi pubmed - Qaseem A, Etxeandia-Ikobaltzeta I, Lin JS, et al. Diagnosis and management of acute left-sided colonic diverticulitis: a clinical guideline from the american college of physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175(3):399-415.

doi - Hall J, Hardiman K, Lee S, Lightner A, Stocchi L, Paquette IM, Steele SR, et al. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons Clinical Practice Guidelines for the treatment of left-sided colonic diverticulitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2020;63(6):728-747.

doi pubmed - Sartelli M, Weber DG, Kluger Y, Ansaloni L, Coccolini F, Abu-Zidan F, Augustin G, et al. 2020 update of the WSES guidelines for the management of acute colonic diverticulitis in the emergency setting. World J Emerg Surg. 2020;15(1):32.

doi pubmed - Ayoub M, Faris C, Chumbe JT, Anwar N, Chela H, Daglilar E. Outpatient use of antibiotics in uncomplicated diverticulitis decreases hospital admissions. Immun Inflamm Dis. 2024;12(9):e70031.

doi pubmed - Dalby HR, Orru A, Sundh F, Buchwald P, Brannstrom F, Hansske B, Haapaniemi S, et al. Management of acute uncomplicated diverticulitis and adherence to current guidelines-a multicentre SNAPSHOT study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2024;39(1):128.

doi pubmed - Meyer J, Orci LA, Combescure C, Balaphas A, Morel P, Buchs NC, Ris F. Risk of colorectal cancer in patients with acute diverticulitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(8):1448-1456.e1417.

doi pubmed - Thornblade LW, Simianu VV, Davidson GH, Flum DR. Elective surgery for diverticulitis and the risk of recurrence and ostomy. Ann Surg. 2021;273(6):1157-1164.

doi pubmed - Violi A, Cambie G, Miraglia C, Barchi A, Nouvenne A, Capasso M, Leandro G, et al. Epidemiology and risk factors for diverticular disease. Acta Biomed. 2018;89(9-S):107-112.

doi pubmed - Taher R, Kopelman Y, Zeina AR, Mari A, Abu Baker F. Predictors of clinical course and outcomes of acute diverticulitis: the role of age and ethnicity. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57(11).

doi pubmed - Klang E, Freeman R, Levin MA, Soffer S, Barash Y, Lahat A. Machine learning model for outcome prediction of patients suffering from acute diverticulitis arriving at the emergency department-a proof of concept study. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021;11(11).

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Gastroenterology Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.