| Gastroenterology Research, ISSN 1918-2805 print, 1918-2813 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, Gastroenterol Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://gr.elmerpub.com |

Original Article

Volume 000, Number 000, October 2025, pages 000-000

Efficacy and Safety of Tofacitinib for Acute Severe Ulcerative Colitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Gregory Brennana, b, f, Gilmara Coelho Meinec, Lucas Monteiro Delgadod, Paula Santoe

aGI Alliance, Mansfield, TX, USA

bDepartment of Internal Medicine, University of North Texas Health Science Center, Arlington, TX, USA

cDepartment of Internal Medicine, Feevale University, Novo Hamburgo, Brazil

dDepartment of Internal Medicine, Federal University of Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil

eDepartment of Internal Medicine & Diagnostic Imaging and Specialized Diagnosis Unit, University Hospital of Federal University of Sao Carlos, Sao Carlos, Brazil

fCorresponding Author: Gregory Brennan, GI Alliance, Mansfield, TX 76063, USA

Manuscript submitted September 3, 2025, accepted October 1, 2025, published online October 10, 2025

Short title: Tofacitinib for Acute Severe Ulcerative Colitis

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/gr2086

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Acute severe ulcerative colitis (ASUC) is associated with a high risk of colectomy. About 30% of patients do not respond to steroids, requiring rescue therapy. This study aims to evaluate the efficacy and safety of tofacitinib in ASUC.

Methods: MEDLINE, Embase, and Cochrane Library were systematically searched. We used random-effects model to calculate pooled proportions with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For outcomes with ≥ 2 comparative studies, we conducted pairwise meta-analyses and calculated pooled odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs.

Results: We included six studies. Tofacitinib had a 90-day colectomy rate of 15.1% (95% CI: 8.5-25.3%). The clinical response rate at weeks 12 - 14 was 45.4% (95% CI: 32.6-58.9%), and at week 52 was 30.0% (95% CI: 17.4-46.5%). The clinical remission rate at weeks 12 - 14 was 38.1% (95% CI: 28.7-48.5%), and at week 52 was 27.1% (95% CI: 15.2-43.5%). Steroid-free clinical remission rate was 28.6% (95% CI: 22.2-36.1%) at weeks 12 - 14 and 33.1% (95% CI: 25.6-41.6%) at week 52. The most common adverse events were Clostridioides difficile infection, nausea, cardiovascular events, arthralgia or myalgia, herpes zoster infection, venous thromboembolism, and pneumonia. There was no significant difference in 90-day colectomy rate between tofacitinib and control (OR: 0.52; 95% CI: 0.25 - 1.08; P = 0.08).

Conclusion: Tofacitinib demonstrated high clinical response and remission rates, and low adverse events rate. Additionally, there was a trend toward a lower 90-day colectomy rate compared to controls.

Keywords: Ulcerative colitis; Tofacitinib; Acute severe ulcerative colitis

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic inflammatory disease involving the colon, typically beginning in the rectum and extending proximally. It is associated with significant morbidity, and its incidence is rising worldwide [1]. Patients with acute severe ulcerative colitis (ASUC) present with severe symptoms and signs of systemic toxicity [2]. ASUC is a medical emergency requiring hospitalization for intensive medical management. Despite advances in treatment, patients with ASUC are at high risk of colectomy, with up to 20-40% undergoing rescue surgery [1, 3-7].

In hospitalized adult patients with ASUC, intravenous corticosteroids remain the first-line treatment, while infliximab or cyclosporine are the recommended options for patients who are refractory to corticosteroids. However, failure of anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) biologic therapy has been increasingly recognized [1], prompting interest in alternative treatments such as tofacitinib [8, 9].

Tofacitinib, an oral small-molecule Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor, modulates immune responses by targeting the JAK-signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) signaling pathway, thereby reducing inflammation. Currently, it is approved for the treatment of moderate-to-severe UC, particularly in patients with prior anti-TNF exposure [10].

Initial evidence supporting the use of tofacitinib in ASUC came from case reports and small observational studies. However, recent data from comparative studies have reinforced and expanded upon these earlier findings [11, 12]. Thus, this systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to assess the efficacy and safety of tofacitinib for treating patients with ASUC.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

Protocol and registration

We performed the systematic review and meta-analysis according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and structured it according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [13]. The study protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) under registration number CRD420250651197.

Outcomes and additional analysis

The primary outcome was 90-day colectomy rate. Secondary outcomes were: 1) clinical response at week 12 - 14, 2) clinical response at week 52, 3) clinical remission at week 12 - 14, 4) clinical remission at week 52, 5) steroid-free clinical remission at week 12 - 14, 6) steroid-free clinical remission at week 52, and 7) adverse events (AEs) by type. The definitions of clinical response, remission, and steroid-free clinical remission for each included study are presented in Supplementary Table 1 (gr.elmerpub.com).

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion in this meta-analysis was limited to studies that included a minimum of 10 adult patients with ASUC, preferably defined based on Truelove-Witts criteria [2] or as cases requiring hospitalization with severe symptoms and/or severe endoscopic disease, treated with tofacitinib, and reporting at least one prespecified outcome of interest. Only original, full-text, peer-reviewed articles in English were included.

Studies were excluded if they included patients with mild, moderate, or severe disease treated in an outpatient setting, as well as those involving patients with Crohn’s disease or indeterminate colitis. Case reports, case series, editorials, letters to the editor, and literature reviews were also excluded.

Search strategy and study selection

We searched PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Library databases to identify studies meeting the inclusion criteria until February 2025. The search strategy was: (Tofacitinib OR Xeljanz OR Jaquinus) AND severe AND “ulcerative colitis.” We also searched the references of the included studies and previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses aiming for the inclusion of additional studies.

Two authors (GB and LMD) independently conducted the search, imported results into Rayyan Software (Qatar Computing Research Institute, Qatar Foundation, Doha, Qatar), and triaged the studies. After the exclusion of duplicates and titles/abstracts unrelated to the clinical question, the eligibility of each remaining study was assessed based on the review of the full-text articles. Disagreements were solved by a third author (GCM).

Data extraction

Two authors (GB and LMD) independently extracted data from the included studies using a standardized format. Extracted data included general study information (study title, authors, year of publication, and country), patient characteristics (median age, sex distribution, disease extent, median Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index of Severity (UCEIS), Mayo Endoscopic Score, concomitant steroid use, prior anti-TNF exposure). Additionally, study design, number of participants, ASUC diagnostic criteria, tofacitinib dose, and follow-up duration were recorded. Reported outcomes of interest were also extracted.

Risk of bias and evidence quality assessment

The randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were assessed for risk of bias using the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2 (RoB 2) tool [14]. Two authors (GB and LMD) independently evaluated each study for its risk of bias across five domains and assigned a rating of high, low, or some concerns in each one. The risk of bias in observational studies was assessed using the Risk of Bias in Non-Randomized Studies of Interventions Version 2 (ROBINS-I V2) tool [15]. Two independent examiners (GB and LMD) evaluated seven domains of bias: bias due to confounding, bias in the classification of interventions, bias in the selection of participants into the study or analysis, bias due to deviations from intended interventions, bias due to missing data, bias in the measurement of outcomes, and bias in the selection of reported results. The assessment of each domain guided the overall judgment of the risk of bias. In cases of disagreement, the final decision was made through consensus. Publication bias assessment was not possible as our meta-analysis included fewer than 10 studies.

Data analyses

We conducted a single-arm meta-analysis and calculated the pooled proportions of outcomes with their respective 95% CIs using the logit transformation. For binary outcomes with at least two comparative studies available, we also performed a pairwise meta-analysis and calculated the pooled ORs with 95% CIs. Significance was regarded as a P-value < 0.05. We used DerSimonian and Laird random-effects models for all statistical analyses. Between-study heterogeneity was assessed using the Cochran Q test and I2 statistics, and we considered a P-value of < 0.10 and an I2 > 25% as indicative of significant heterogeneity. In cases of significant heterogeneity, a leave-one-out sensitivity analysis was performed. All the statistical analyses were conducted using R statistical software (version 4.3.2; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

| Results | ▴Top |

Study selection and characteristics

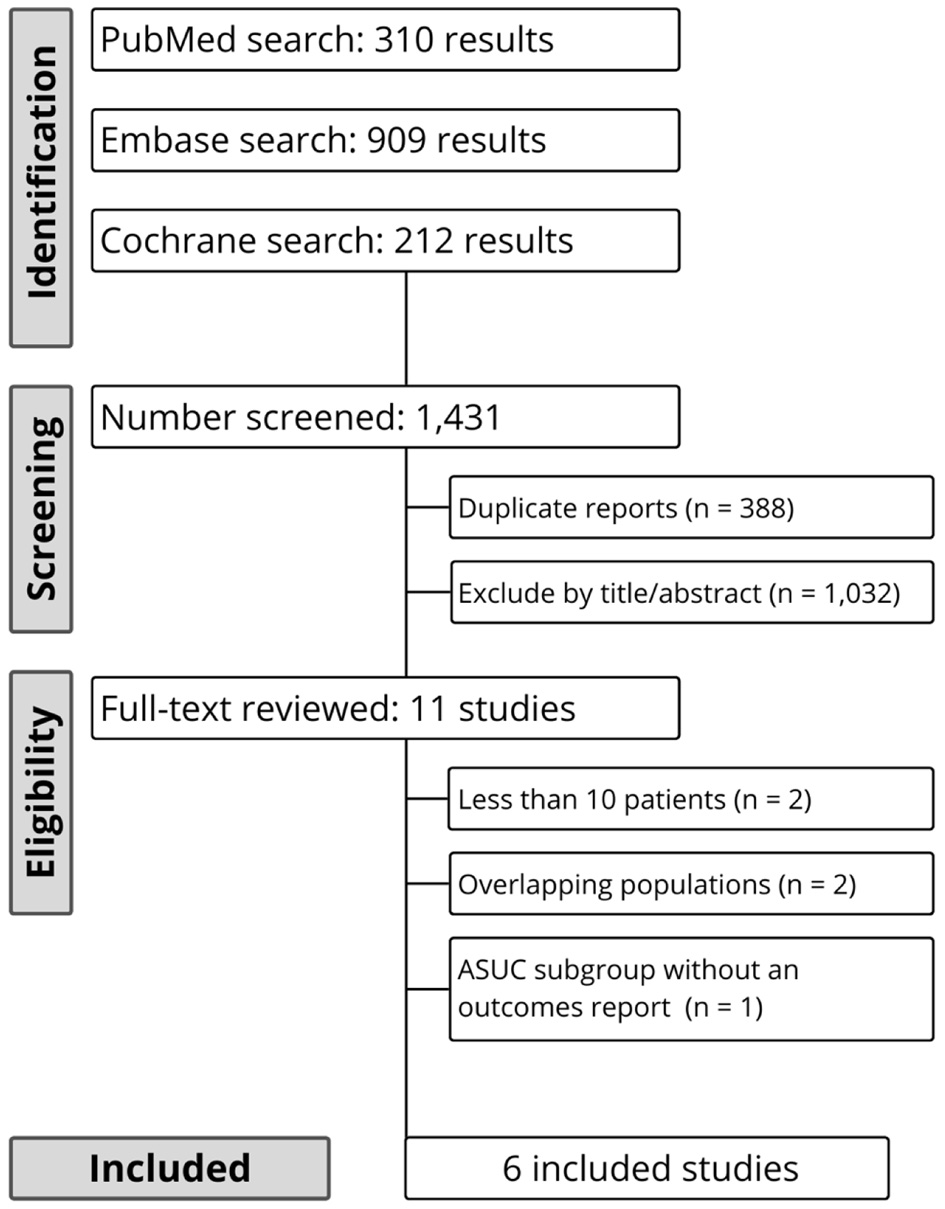

As detailed in Figure 1, the initial search identified 1,431 results. After the removal of duplicate records and assessment of the studies based on title and abstract, 28 studies remained for full-text review according to prespecified criteria. Of these, six studies were selected, comprising a total of 291 patients with ASUC receiving tofacitinib [11, 12, 16-19]. Supplementary Table 2 (gr.elmerpub.com) lists the excluded studies from the full-text screening stage and the reasons for their exclusion. Three studies included a control group, composed of continuing intravenous corticosteroids and placebo [11]; infliximab, cyclosporine, or ustekinumab [17]; or infliximab or cyclosporin [16]. The baseline characteristics are detailed in Table 1. Important study design characteristics and pharmacological treatment in the included studies is detailed in Table 2.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram of study screening and selection. |

Click to view | Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Included Studies |

Click to view | Table 2. Pharmacological Treatment in the Included Studies |

Pooled analyses

Primary outcome

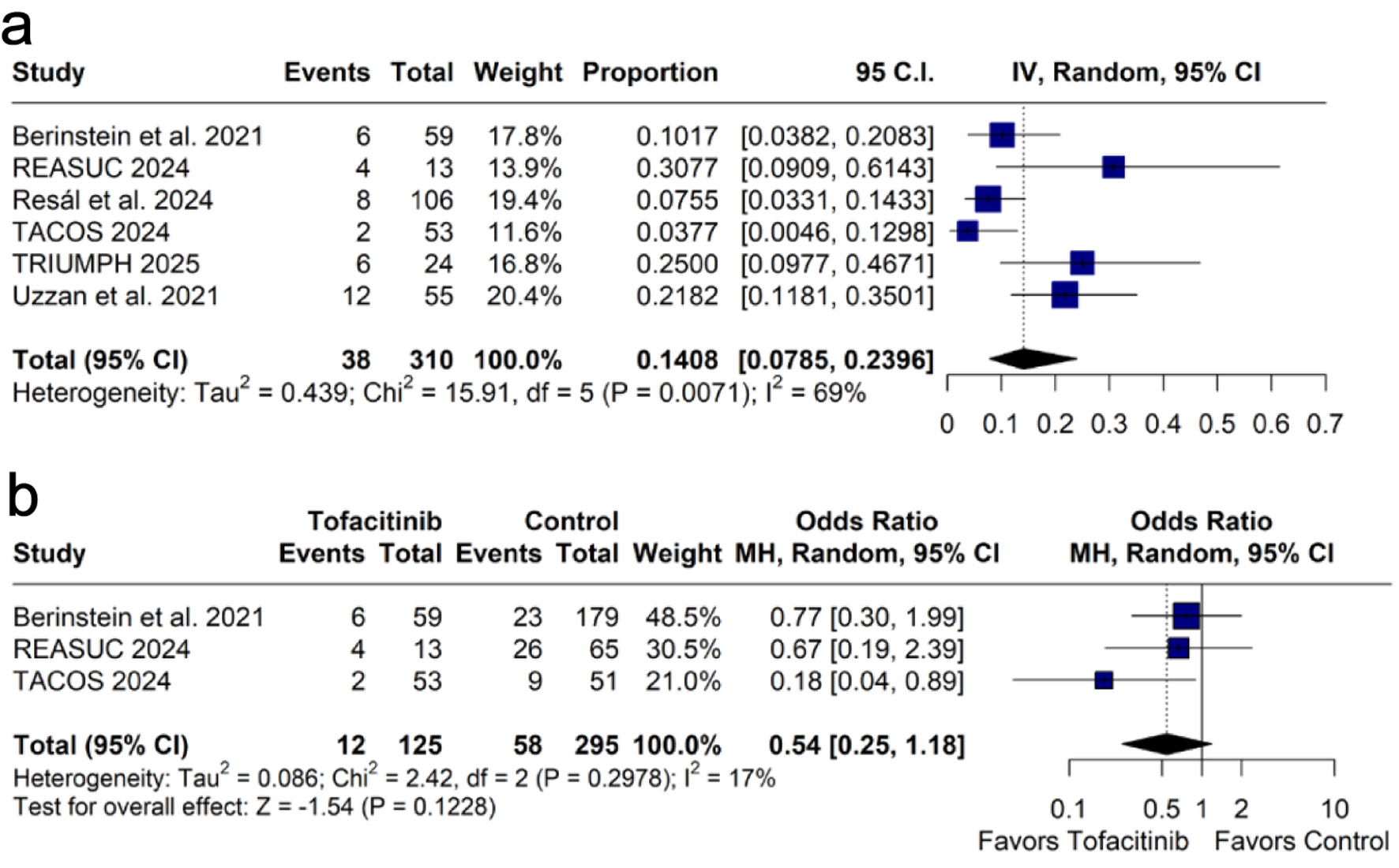

The pooled 90-day colectomy rate with tofacitinib treatment was 15.1% (k = 6 [11, 12, 16-19]; n = 291; 95% CI: 8.5-25.3%; I2 = 66%; Fig. 2a). Comparative meta-analysis showed no statistically significant difference in the 90-day colectomy rate between tofacitinib and control (k = 3 [11, 16, 17]; n = 335; OR: 0.52; 95% CI: 0.25 - 1.08; P = 0.08; I2 = 7%; Fig. 2b).

Click for large image | Figure 2. Forest plots of 90-day colectomy rates: (a) pooled rate of 90-day colectomy; (b) comparison of 90-day colectomy rates between tofacitinib and control groups. CI: confidence interval; IV: inverse variance; MH: Mantel-Haenszel. |

Secondary outcomes

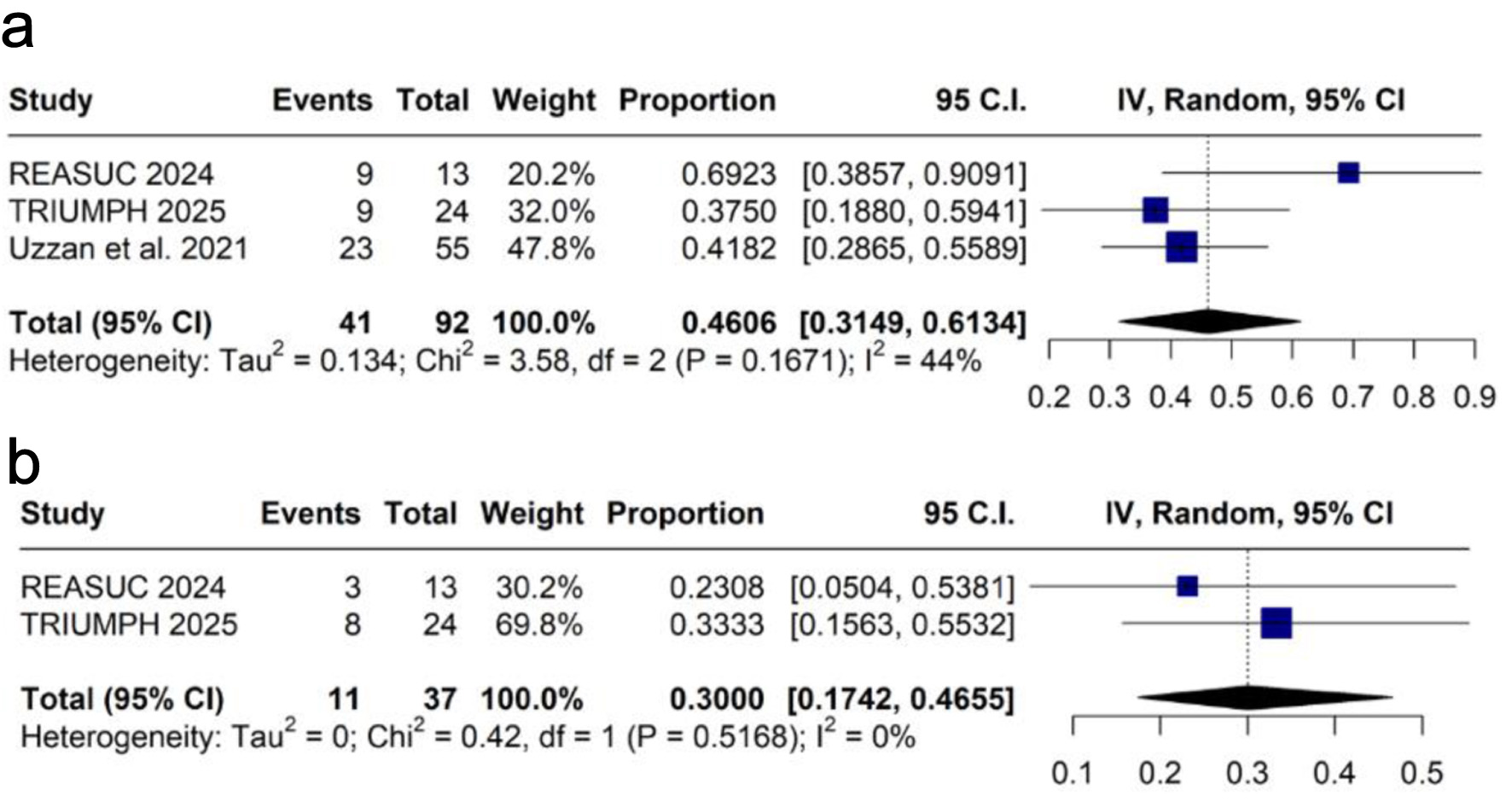

1) Clinical response

Clinical response was assessed at weeks 12 - 14, with a pooled proportion of 45.4% (k = 3 [12, 17, 19]; n = 92; 95% CI: 32.6-58.9%; I2 = 44%; Fig. 3a), and at week 52, with 30.0% (k = 2 [12, 17]; n = 37; 95% CI: 17.4-46.5%; I2 = 0%; Fig. 3b).

Click for large image | Figure 3. Forest plots of clinical response: (a) at weeks 12 - 14; (b) at week 52. CI: confidence interval; IV: inverse variance. |

2) Clinical remission

The pooled proportion of clinical remission at weeks 12 - 14 was 38.1% (k = 3 [12, 17, 19]; n = 92; 95% CI: 28.7-48.5%; I2 = 0%; Fig. 4a), and at week 52 was 27.1% (k = 2 [12, 17]; n = 37; 95% CI: 15.2-43.5%; I2 = 0%; Fig. 4b).

Click for large image | Figure 4. Forest plots of clinical remission: (a) at weeks 12 - 14; (b) at week 52. CI: confidence interval; IV: inverse variance. |

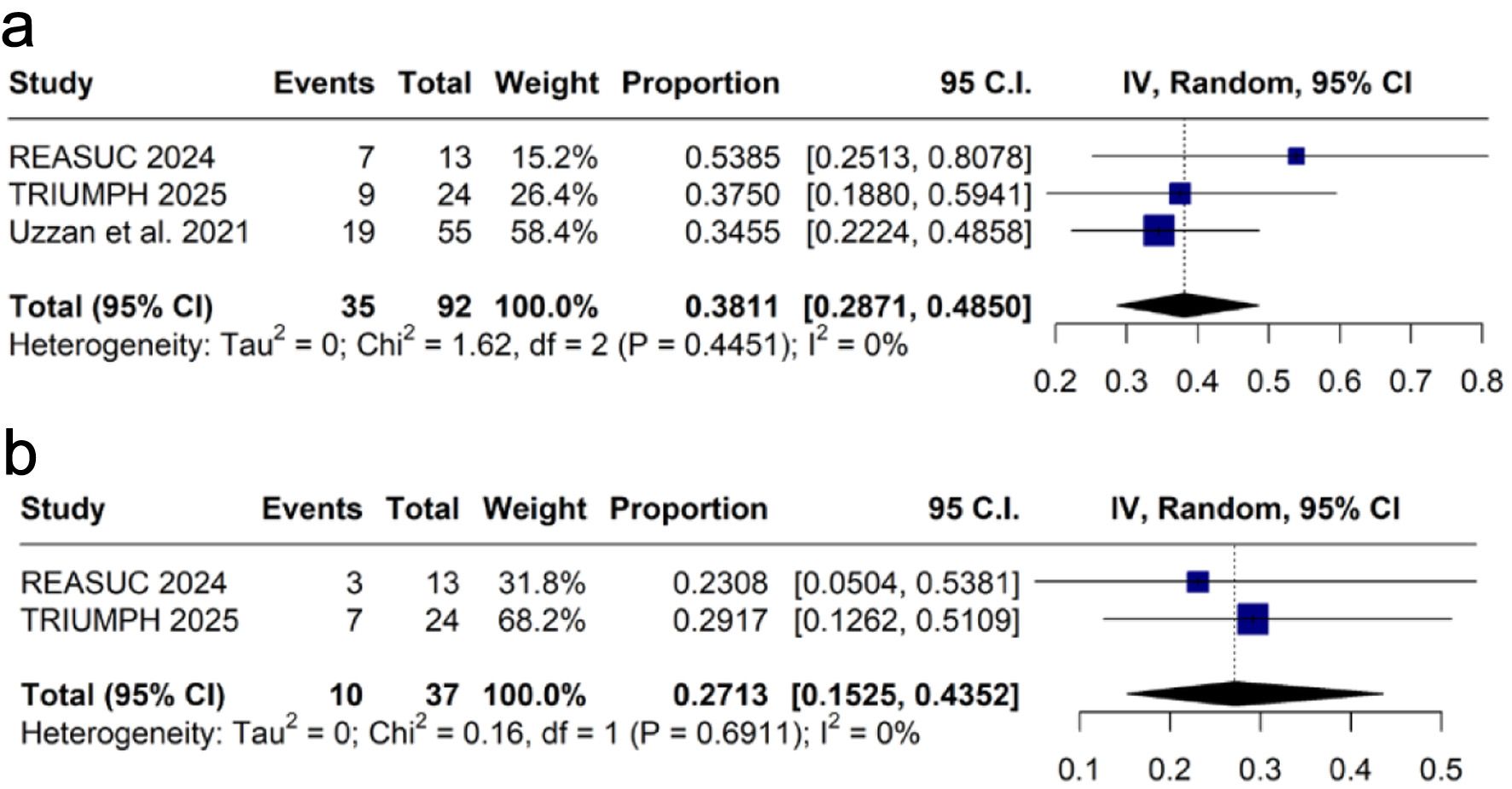

3) Steroid-free clinical remission

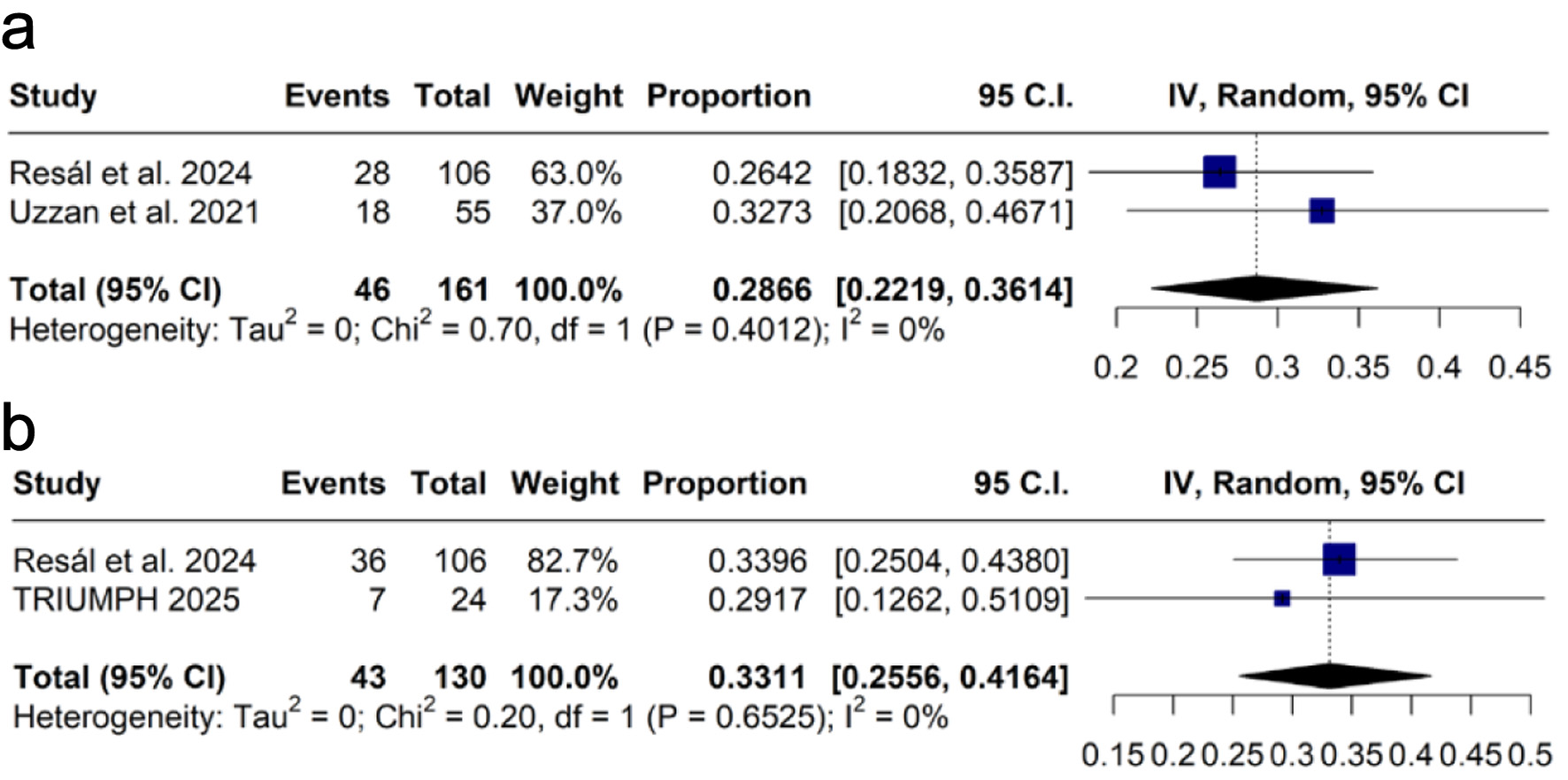

Steroid-free clinical remission was assessed at weeks 12 - 14, with a pooled proportion of 28.6% (k = 2 [18, 19]; n = 46; 95% CI: 22.2-36.1%; I2 = 0%; Fig. 5a), and at week 52, with 33.1% (k = 2 [12, 18]; n = 130, 95% CI: 25.6-41.6%; I2 = 0%; Fig. 5b).

Click for large image | Figure 5. Forest plots of steroid-free clinical remission: (a) at weeks 12 - 14; (b) at week 52. CI: confidence interval; IV: inverse variance. |

4) Safety-related outcomes

The most common AEs were Clostridioides difficile infection (k = 3 [16, 18, 19]; n = 201; 3.1%; 95% CI: 0.6-14.2%; I2 = 67%; Supplementary Figure 1, gr.elmerpub.com), followed by nausea (k = 3 [12, 17, 18]; n = 185; 2.8%; 95% CI: 0.7-10.6%; I2 = 46%; Supplementary Figure 2, gr.elmerpub.com), cardiovascular events (k = 4 [12, 16, 17, 19]; n = 132; 2.6%; 95% CI: 0.7-8.6%; I2 = 0%; Supplementary Figure 3, gr.elmerpub.com), arthralgia or myalgia (k = 3 [12, 16, 17, 19]; n = 172; 2.3%; 95% CI: 0.5-9.5%; I2 = 28%; Supplementary Figure 4, gr.elmerpub.com), herpes zoster infection (k = 4 [11, 12, 18, 19]; n = 254; 2.2%; 95% CI: 0.9-5.1%; I2 = 0%; Supplementary Figure 5, gr.elmerpub.com), venous thromboembolism (k = 4 [11, 12, 18, 19]; n = 172; 1.8%; 95% CI: 0.6-5.6%; I2 = 0%; Supplementary Figure 6, gr.elmerpub.com), and pneumonia (k = 3 [12, 18, 19]; n = 201; 1.6%; 95% CI: 0.5-4.9%; I2 = 0%; Supplementary Figure 7, gr.elmerpub.com).

Sensitivity analysis

Leave-one-out sensitivity analyses were performed in cases of significant heterogeneity. The sensitivity analysis for the 90-day colectomy rate showed that no single study had significant impact on heterogeneity (Supplementary Figure 8, gr.elmerpub.com). For clinical response at weeks 12 - 14, the study REASUC 2024 [17] was identified as the main source of heterogeneity, and its removal eliminated the heterogeneity (Supplementary Figure 9, gr.elmerpub.com). Among the AEs, the removal of Berinstein et al [16] for Clostridioides difficile infection, (Supplementary Figure 10, gr.elmerpub.com), TRIUMPH 2025 [12] for nausea (Supplementary Figure 11, gr.elmerpub.com), and REASUC 2024 [17] for arthralgia or myalgia (Supplementary Figure 12, gr.elmerpub.com) eliminated the heterogeneity. However, none of these exclusions significantly impacted the overall effect estimates.

Risk of bias

Supplementary Tables 3 and 4 (gr.elmerpub.com) present the risk of bias assessment.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, tofacitinib was associated with a low pooled 90-day colectomy rate of 15.1% in patients with ASUC. Additionally, tofacitinib showed a trend toward a reduced 90-day colectomy rate compared to the control group (P = 0.08). Additionally, tofacitinib demonstrated pooled rates of clinical response in 45.4% of patients, clinical remission in 38.1%, and steroid-free remission in 28.6% at weeks 12 - 14. At week 52, the pooled rates of clinical response, clinical remission, and steroid-free remission were 30.0%, 27.1%, and 33.1%. These findings suggest favorable efficacy for tofacitinib in this patient population.

Here, we provide the most comprehensive and up-to-date analysis of the efficacy and safety of tofacitinib in treating ASUC. Two systematic reviews on this topic were published in 2023. One included 148 adult and pediatric patients [8], showing a pooled 86% colectomy-free survival at 90 days. The other included 134 adult patients with a 79.9% pooled 90-day colectomy-free survival rate [9]. However, these reviews included low-quality uncontrolled studies, such as small case series and case reports. Since these publications, new prospective and comparative trials have been published, which we have included in our analysis.

The TACOS study [11] was a randomized placebo-controlled trial published in 2024. This is a landmark study being the first and only RCT evaluating the safety and efficacy of tofacitinib in ASUC. A total of 104 ASUC patients were randomly assigned to receive either tofacitinib (10 mg three times daily (TID) for 7 days) or placebo with both arms receiving standard of care consisting of intravenous hydrocortisone. After day 7, unblinding occurred, and in responders, tofacitinib was adjusted to 10 mg twice daily (BID), while steroid tapering was started. At day 7, 83% of patients receiving tofacitinib had clinical response vs. 58% of those receiving placebo. Those failing to initially respond received “rescue therapy” with either infliximab or colectomy. The need for rescue therapy was significantly lower in the tofacitinib group (11.3%) compared to placebo (31.3%) at day 7, as were at all other time points up until 90 days. At 90 days, two patients required colectomy, and one patient died in the tofacitinib arm, compared to eight colectomies and four deaths in the placebo arm. AEs were more common with tofacitinib [13] compared to placebo [7].

In the open-label prospective TRIUMPH trial published in 2025 [12], 24 steroid-refractory ASUC patients across five centers in Canada were treated with tofacitinib 10 mg BID. This trial included both anti-TNF exposed and naive patients who were refractory to 3 days of intravenous corticosteroids. There was no control arm in this study. Two patients required colectomy within 90 days, and six patients at 6 months follow-up. Clinical response was achieved rapidly at 2.4 days and 58% of patients achieved clinical response by day 7. At week 12, 37.5% had a clinical response and clinical remission. Overall, five patients experienced an AE. There was one stroke reported, but it was unlikely related to tofacitinib, given the patient’s underlying comorbidities.

Real-world evidence plays an important role in informing medical decision-making for patients with ASUC in the absence of controlled trials. Here, we have selected the highest quality real-world studies for inclusion [16-19]. Berinstein et al [16] conducted a case-control study comparing ASUC patients treated with various doses of tofacitinib matched 1:3 with controls that received either infliximab or cyclosporine. Both groups received concomitant intravenous corticosteroids. The 90-day colectomy rate in the tofacitinib group was 15% compared to 20.4% in the control group. The REASUC [17] study examined the efficacy of third-line therapies for steroid-refractory ASUC patients who had failed either infliximab or ciclosporin. The rate of colectomy in the tofacitinib group was 30.7% vs. 40% in the control group.

Uzzan et al [19] conducted a multicenter cohort study using both respective and prospective data on patients hospitalized with UC flare receiving tofacitinib as rescue therapy. The majority were treated with concomitant steroids (65.5%) and all but one patient had a history of anti-TNF failure. At 90 days, the colectomy free survival was 78.9%. Resal et al [18] published a multicenter cohort study examining the safety and efficacy of tofacitinib treatment in both ASUC patients and chronic steroid dependent UC patients (Of note, in our analysis we only included the subgroup of patients with ASUC). In the ASUC group, the 90-day colectomy rate (defined as week 12 in the study) was 7.5%.

Combining the results of the comparative studies [11, 16, 17], our pairwise meta-analysis showed a trend toward lower rates of 90-day colectomy in the tofacitinib group compared to the control group. Despite not reaching statistical significance (P = 0.08), there was low between-study heterogeneity (I2 = 7%). Further studies with larger sample sizes may help determine whether this trend represents a true clinical benefit.

The safety of tofacitinib has been studied in previous trials [10, 20]. Concerns for AEs, such as major adverse cardiovascular events and infectious complications, are of particular interest since patients with ASUC have a high inflammatory burden and usually require immunosuppressive therapies [1]. In our study, patients with ASUC treated with tofacitinib showed rates of cardiovascular events of 2.6%, venous thromboembolism of 1.8%, Clostridioides difficile infection of 3.1%, herpes zoster of 2.2%, and pneumonia of 1.6%. In the OCTAVE open label extension study [20], which followed patients up to 7 years, the rate of deep vein thrombus was under 1%, major adverse cardiovascular events was 4%, and herpes zoster was approximately 7%. We hypothesize that any difference reported in ASUC patients is likely due to increased inflammatory burden and disease severity since the OCTAVE trials included patients in remission on long-term treatment.

This study has several strengths. First, we used rigorous methods specified in the meta-analysis protocol. Second, this is the most comprehensive meta-analysis assessing the efficacy and safety of tofacitinib for treating patients with ASUC, with the largest proportion of patients from prospective trials and comparative studies. Third, the studies were conducted in various countries, enhancing the generalizability of our results. Finally, in addition to single-arm analysis, we also performed pairwise analysis when available.

However, our meta-analysis also has important limitations. Four of the six included studies were observational and thus at risk for confounding factors. Noteworthy, one of those studies had a matched cohort, minimizing the potential for bias. Additionally, there were several differences in study designs, definitions, and pharmacological therapies across the included studies. For example, the definition of ASUC was not standardized, but we only included studies that provided a definition consistent with our real-world experience in classifying acutely ill hospitalized patients with severe disease activity. Prospective studies comparing tofacitinib to standard treatments for ASUC are still needed.

In conclusion, tofacitinib demonstrated high clinical response and remission rates, along with a low AEs rate. Additionally, there was a non-significant trend toward a lower 90-day colectomy rate compared to the control group. However, comparative data were scarce, and further prospective comparative studies are needed to elucidate the differences between this approach and current ASUC therapies.

| Supplementary Material | ▴Top |

Supplementary Table 1. Definitions of clinical response, remission, and steroid-free clinical remission for each included study.

Supplementary Table 2. List of excluded studies at the full-text screening stage and the reasons for exclusion.

Supplementary Table 3. Risk of bias summary for randomized studies (RoB 2).

Supplementary Table 4. Risk of bias summary for non-randomized studies (ROBINS-I).

Supplementary Figure 1. Forest plot for Clostridioides difficile infection.

Supplementary Figure 2. Forest plot for nausea. CI: confidence interval; IV: inverse variance.

Supplementary Figure 3. Forest plot for cardiovascular events. CI: confidence interval; IV: inverse variance.

Supplementary Figure 4. Forest plot for arthralgia or myalgia. CI: confidence interval; IV: inverse variance.

Supplementary Figure 5. Forest plot for herpes zoster infection. CI: confidence interval; IV: inverse variance.

Supplementary Figure 6. Forest plot for venous thromboembolism. CI: confidence interval; IV: inverse variance.

Supplementary Figure 7. Forest plot for pneumonia. CI: confidence interval; IV: inverse variance.

Supplementary Figure 8. Leave-one-out analysis for 90-day colectomy rate. CI: confidence interval.

Supplementary Figure 9. Leave-one-out analysis for clinical response at weeks 12 - 14. CI: confidence interval.

Supplementary Figure 10. Leave-one-out analysis for Clostridioides difficile infection. CI: confidence interval.

Supplementary Figure 11. Leave-one-out analysis for nausea. CI: confidence interval.

Supplementary Figure 12. Leave-one-out analysis for arthralgia or myalgia. CI: confidence interval.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no competing interests or funding sources to disclose.

Informed Consent

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

Conception and design: GB and GM. Acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data: GB, GM, LD, and PS. Drafting and editing the manuscript: GB, GM, LD, and PS. Revising it critically for important intellectual content: GB, GM, LD, and PS. Final approval of the version to be published: GB and GM. Guarantor of the article: GB. All authors take responsibility for all aspects of the reliability and freedom from bias of the data presented and their discussed interpretation.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article. This systematic review and meta-analysis used publicly available data from the researched databases. No new datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Abbreviations

AEs: adverse events; ASUC: acute severe ulcerative colitis; CI: confidence interval; JAK: Janus kinase; PRISMA: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis; PROSPERO: International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews; RCT: randomized controlled trial; RR: risk ratio; STAT: signal transducers and activators of transcription; TNF: tumor necrosis factor; UC: ulcerative colitis; UCEIS: Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index of Severity

| References | ▴Top |

- Rubin DT, Ananthakrishnan AN, Siegel CA, Sauer BG, Long MD. ACG clinical guideline: ulcerative colitis in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114(3):384-413.

doi pubmed - Truelove SC, Witts LJ. Cortisone in ulcerative colitis; final report on a therapeutic trial. Br Med J. 1955;2(4947):1041-1048.

doi pubmed - Dinesen LC, Walsh AJ, Protic MN, Heap G, Cummings F, Warren BF, George B, et al. The pattern and outcome of acute severe colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4(4):431-437.

doi pubmed - Feuerstein JD, Isaacs KL, Schneider Y, Siddique SM, Falck-Ytter Y, Singh S, AGA Institute Clinical Guidelines Committee. AGA clinical practice guidelines on the management of moderate to severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(5):1450-1461.

doi pubmed - Chaaban L, Cohen B, Cross RK, Kayal M, Long M, Ananthakrishnan A, Melia J. Predicting outcomes in hospitalized patients with acute severe ulcerative colitis in a prospective multicenter cohort. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2025;31(6):1548-1555.

doi pubmed - Bourgonje AR, Posner H, Carbonnel F, Colombel JF, Kayal M. Prior anti-TNF exposure is associated with an increased risk of short- and long-term colectomy in acute severe ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2025;70(2):738-745.

doi pubmed - Moore AC, Bressler B. Acute severe ulcerative colitis: the Oxford criteria no longer predict in-hospital colectomy rates. Dig Dis Sci. 2020;65(2):576-580.

doi pubmed - Steenholdt C, Dige Ovesen P, Brynskov J, Seidelin JB. Tofacitinib for acute severe ulcerative colitis: a systematic review. J Crohns Colitis. 2023;17(8):1354-1363.

doi pubmed - Mpakogiannis K, Fousekis FS, Christodoulou DK, Katsanos KH, Narula N. The current role of tofacitinib in acute severe ulcerative colitis in adult patients: A systematic review. Dig Liver Dis. 2023;55(10):1311-1317.

doi pubmed - Sandborn WJ, Su C, Sands BE, D'Haens GR, Vermeire S, Schreiber S, Danese S, et al. Tofacitinib as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(18):1723-1736.

doi pubmed - Singh A, Goyal MK, Midha V, Mahajan R, Kaur K, Gupta YK, Singh D, et al. Tofacitinib in acute severe ulcerative colitis (TACOS): a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024;119(7):1365-1372.

doi pubmed - Narula N, Pray C, Hamam H, Peerani F, Hansen T, Bessissow T, Bressler B, et al. Tofacitinib for hospitalized acute severe ulcerative colitis management (The TRIUMPH Study). Crohns Colitis 360. 2025;7(1):otaf013.

doi pubmed - Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2021;372:n71.

doi pubmed - Sterne JAC, Savovic J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, Cates CJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898.

doi pubmed - Sterne JA, Hernan MA, Reeves BC, Savovic J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, Henry D, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919.

doi pubmed - Berinstein JA, Sheehan JL, Dias M, Berinstein EM, Steiner CA, Johnson LA, Regal RE, et al. Tofacitinib for biologic-experienced hospitalized patients with acute severe ulcerative colitis: a retrospective case-control study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19(10):2112-2120.e2111.

doi pubmed - Garcia MJ, Riestra S, Amiot A, Julsgaard M, Garcia de la Filia I, Calafat M, Aguas M, et al. Effectiveness and safety of a third-line rescue treatment for acute severe ulcerative colitis refractory to infliximab or ciclosporin (REASUC study). Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2024;59(10):1248-1259.

doi pubmed - Resal T, Bacsur P, Keresztes C, Balint A, Bor R, Fabian A, Farkas B, et al. Real-life efficacy of tofacitinib in various situations in ulcerative colitis: a retrospective worldwide multicenter collaborative study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2024;30(5):768-779.

doi pubmed - Uzzan M, Bresteau C, Laharie D, Stefanescu C, Bellanger C, Carbonnel F, Serrero M, et al. Tofacitinib as salvage therapy for 55 patients hospitalised with refractory severe ulcerative colitis: A GETAID cohort. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2021;54(3):312-319.

doi pubmed - Sandborn WJ, Lawendy N, Danese S, Su C, Loftus EV, Jr., Hart A, Dotan I, et al. Safety and efficacy of tofacitinib for treatment of ulcerative colitis: final analysis of OCTAVE Open, an open-label, long-term extension study with up to 7.0 years of treatment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022;55(4):464-478.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Gastroenterology Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.