| Gastroenterology Research, ISSN 1918-2805 print, 1918-2813 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, Gastroenterol Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://gr.elmerpub.com |

Original Article

Volume 000, Number 000, March 2025, pages 000-000

Comparative Outcomes of Transabdominal and Transperineal Approaches for Full-Thickness Rectal Prolapse Repair: A Fourteen-Year Retrospective Study

Putticha Keawmaneea, Suppadech Tunruttanakula, b , Thansit Srisombuta, Borirak Chareonsila

aDepartment of Surgery, Sawanpracharak Hospital, Muang, Nakhon Sawan 60000, Thailand

bCorresponding Author: Suppadech Tunruttanakul, Department of Surgery, Sawanpracharak Hospital, Muang, Nakhon Sawan 60000, Thailand

Manuscript submitted January 8, 2025, accepted March 6, 2025, published online March 18, 2025

Short title: Comparing Rectal Prolapse Repair

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/gr2015

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: The choice between transabdominal and transperineal approaches for full-thickness rectal prolapse repair remains controversial. This study compared the outcomes of these two approaches over a 14-year period in a real-world setting.

Methods: This retrospective cohort study was conducted at a tertiary hospital in Thailand and included data from surgeries performed between January 2010 and December 2023. All patients who underwent surgical repair were included, except those with rectal prolapse secondary to colorectal cancer or those who did not receive surgical treatment. Surgical approaches were categorized into transperineal and transabdominal repairs. Outcomes (recurrence, morbidity, fecal incontinence, and constipation) were compared using inverse probability treatment weighting of propensity scores.

Results: A total of 58 patients were included, with 33 undergoing transperineal and 25 transabdominal repairs. Thirty-day postoperative complications and recurrence rates were comparable between the two approaches, with a nonsignificant trend favoring the transabdominal approach (30-day postoperative complication and recurrence risk ratios (95% confidence interval (CI)): 0.67 (0.06, 7.65) and 0.62 (0.11, 3.53), respectively). Fecal incontinence and constipation rates were also comparable. However, among the 34 patients with at least a 1-year follow-up, the transabdominal approach showed a nonsignificant trend toward higher constipation and lower fecal incontinence (constipation and fecal incontinence risk ratios (95% CI): 2.24 (0.61, 8.19) and 0.50 (0.16, 1.60), respectively).

Conclusions: From our 14 years of experience, transperineal and transabdominal approaches for rectal prolapse repair have had comparable outcomes. The choice of approach should be based on patient conditions, surgeon expertise, and thorough discussion with all involved.

Keywords: Colorectal surgery; Comparative study; Propensity score; Rectal prolapse

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Rectal prolapse is a condition where varying degrees of the rectum protrude from the anus [1]. Complete (full-thickness) rectal prolapse is a rare condition (approximately 2.5 per 100,000 people) and is diagnosed when the entire rectal wall protrudes from the anal canal [1, 2]. Rectal prolapse can affect quality of life due to discomfort, discharge, fecal incontinence, and constipation, and sometimes presents with incarceration, requiring emergency surgical treatment [3].

Surgical treatment is usually required for high-degree prolapse [3]. However, since one of the causes of prolapse is a degenerative process due to prolonged wear and tear, patients with high-degree rectal prolapse are usually elderly and frail [2], making surgical decisions challenging. Moreover, there are several surgical options for correcting rectal prolapse [3]. Broadly, surgical correction of the rectal prolapse can be categorized into transperineal and transabdominal approaches. In brief, the transperineal approach is believed to be less invasive but has a higher recurrence rate, while the transabdominal approach is more invasive but has a lower recurrence rate [4, 5]. However, this basic theory is still controversial, and many published studies have shown conflicting results [6]. Most of the data also came from universities or large specialist institutes. In this study, we aimed to present over a decade of experience (14 years) with complete rectal prolapse repair at a tertiary hospital in an upper-middle-income country (Thailand). The primary objective was to compare the outcomes of transperineal versus transabdominal approaches, with the hope that our findings will contribute to a deeper understanding of full-thickness rectal prolapse repairs.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

Patient selection and clinical characteristics

We conducted a retrospective cohort study involving patients diagnosed with complete (full-thickness) rectal prolapse who underwent surgical correction at Sawanpracharak Hospital, a tertiary government hospital located in the lower northern region of Thailand. The study period spanned from January 1, 2010, to December 31, 2023. The selected time frame and data acquisition were based on the availability of records in the hospital’s electronic data archiving system. The study included patients with complete rectal prolapse who received surgical correction and excluded cases secondary to colorectal cancer and those who did not receive surgical treatment.

All included patients underwent a preoperative risk assessment conducted by an anesthesiologist, with additional cardiac evaluations performed by a cardiologist when necessary. The following parameters were collected: patient age, sex, body mass index, comorbidity details, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) status, surgery duration (in minutes), and estimated blood loss. Multimorbidity was defined as the presence of two or more comorbidities, in accordance with established criteria [7]. Bedridden patients were also classified as having multimorbidity. ASA status and estimated blood loss, determined through visual estimation, were assessed by the attending anesthesiologists. The urgency of surgery (nonelective/unplanned surgery) was also documented. The diagnosis of complete rectal prolapse was based on clinical assessment, with a primary focus on physical examination, confirming rectal protrusion through the anal canal [8]. In our setting, preoperative investigations were routinely conducted exclusively to rule out secondary rectal prolapse such as colorectal cancer or polyps [3, 8]. The diagnostic workup included either a barium enema or colonoscopy. Due to their unavailability, functional tests such as anorectal manometry or defecography were not performed.

The primary outcomes measured were postoperative complications within 30 days and the incidence of recurrence requiring repeat surgical intervention. Secondary outcomes included the incidence of postoperative constipation, fecal incontinence, and the length of hospital stay. Due to the rarity of rectal prolapse, our department does not have an established follow-up protocol. However, follow-up duration was collected and analyzed as part of a sensitivity analysis. To our knowledge, specific diagnostic criteria for postoperative constipation and fecal incontinence are not currently available. Therefore, we adapted the Rome IV diagnostic criteria for constipation and fecal incontinence to identify these postoperative complications [9].

Our primary focus was on the surgical approaches used for rectal prolapse repair. Given the variety of procedures performed at our institute, we categorized the surgeries into two main approaches: Transabdominal (via laparotomy or laparoscopy) and transperineal (via the perineum). Transabdominal procedures included rectopexy with or without resection (sigmoidectomy or rectosigmoidectomy). The laparoscopic repair, introduced later at our institute, was classified under the transabdominal category and specifically involved laparoscopic ventral mesh rectopexy [10]. Transperineal procedures comprised rectal mucosal excision with plication of the rectal wall (Delorme procedure), anal canal narrowing (Thiersch procedure), and perineal proctosigmoidectomy (Altemeier procedure) [3]. The choice of surgical procedure was made by the in-charge surgeon in consultation with the patient and their relatives, considering multiple factors. Since our setting is not a teaching hospital, surgeon preferences varied based on their individual training and experience. Patients and their families were actively involved in the decision-making process, choosing between the recommended abdominal or perineal approach while weighing the surgical risks and the urgency of the procedure. Our objective was to compare the outcomes of these two primary approaches: transabdominal versus transperineal.

Ethics approval

This study received approval from the Ethics Committee at Sawanpracharak Hospital (Certificate No. 186/66). Data collection commenced following ethical approval, and we strictly adhered to the confidentiality principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. All participant data were anonymized, with no identifiable information included in the analysis. The requirement for patient consent was waived due to the retrospective study design and use of deidentified data.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were applied based on the data type. Categorical data were presented as frequencies and percentages, while continuous data were presented as mean (standard deviation) or median (interquartile range), as appropriate. Fisher’s exact test, t-test, and Mann-Whitney U test were used for univariable analysis.

Inverse probability weighting with propensity score analysis

To adjust for confounders in this observational study, we employed propensity scores with inverse probability weighting. This approach was chosen because propensity score-based methods offer greater integrity for comparative (marginal effect) studies, and using inverse probability weighting helps preserve statistical efficiency in small sample sizes, particularly in studies of rare conditions [11]. The variables included in the propensity score calculation were selected based on their potential as confounders, specifically those influencing the type of surgery chosen (confounding by indication) and prognostic factors [12]. The selected variables included patient age, sex, body mass index, ASA status, and urgency of surgery. ASA status was used to represent multimorbidity and bedridden status. While operative time and estimated blood loss could also impact outcomes, they were considered mediators, as they occur after the exposure (surgical repair) [13].

We evaluated variable balance using mean standardized differences and kernel density plots, which graphically illustrated the propensity score distribution before and after weighting [14]. Transabdominal procedures were weighted by the inverse of their propensity score, while transperineal approaches were weighted by the inverse of one minus their propensity score. After weighting, binary outcomes such as complications, recurrence, fecal incontinence, and constipation were analyzed using binary regression (generalized linear models for the binomial family). Length of hospital stay was analyzed using linear regression after weighting. Missing values were addressed using mean imputation, replacing missing values with the mean of the variable.

A sensitivity analysis was planned to assess outcome integrity by repeating the analysis under two conditions: 1) including only patients with a follow-up period longer than 1 year (excluding those with less than 1 year of follow-up) [15]; and 2) using multimorbidity instead of ASA III status for propensity score calculation. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.050. All analyses were performed using STATA (StataCorp., Stata Statistical Software: Version 16, StataCorp LLC).

| Results | ▴Top |

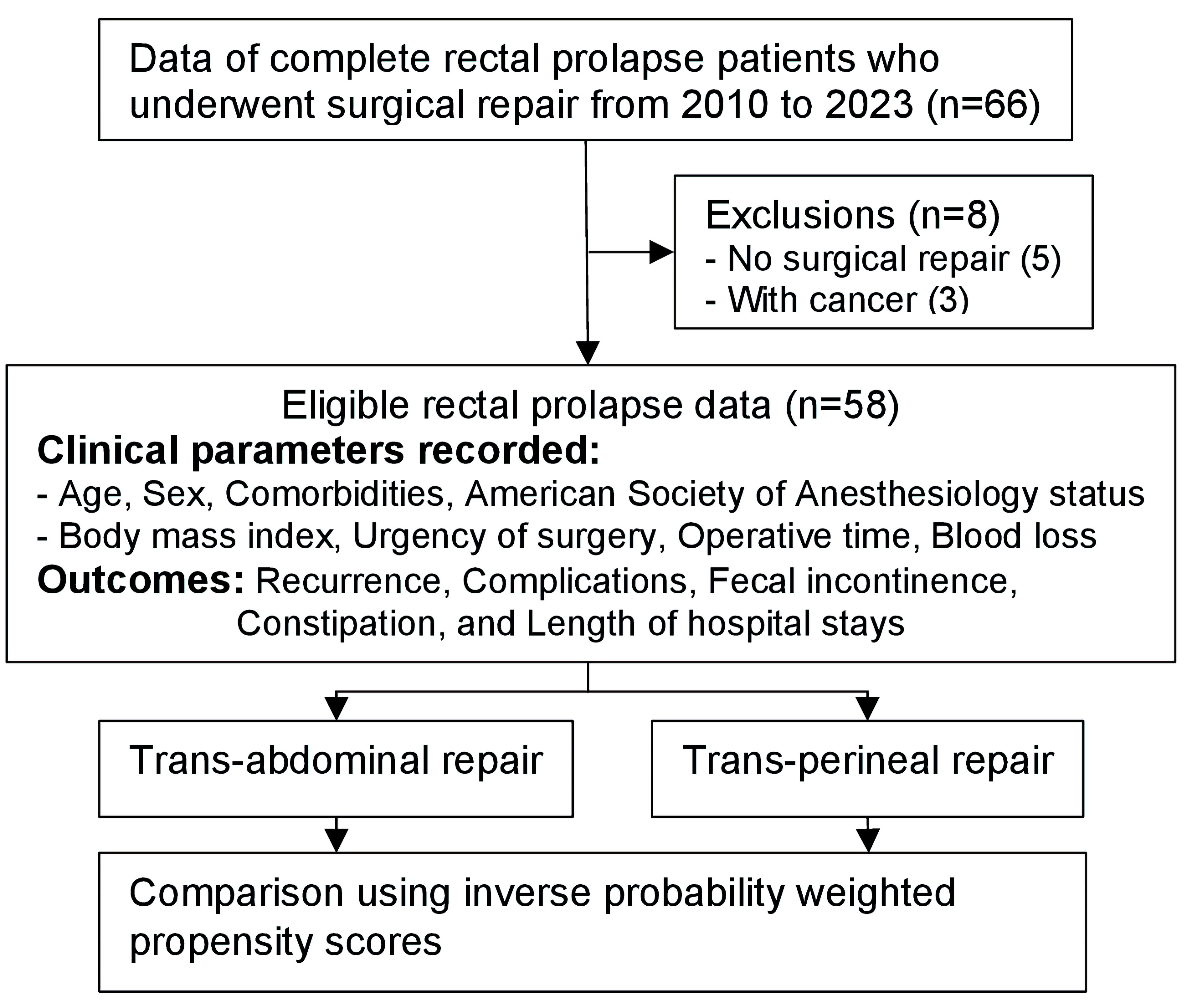

The participant flow is illustrated in Figure 1. During the study period, 66 patients with complete rectal prolapse were identified. Eight patients were excluded: five who did not undergo surgical repair and three whose prolapse was secondary to rectal cancer, leaving 58 eligible patients for analysis. The only missing data were for body mass index, as measurement was not possible for some bedridden or semi-bedridden patients (nine transperineal and two transabdominal). Mean imputation using a body mass index of 21.0 kg/m2 (the mean) was applied.

Click for large image | Figure 1. The study participants’ flow. |

Baseline characteristics of all patients are summarized in Table 1. The cohort included 33 transperineal repairs and 25 transabdominal repairs, with five (20%) of the latter performed using a laparoscopic approach. The transperineal repairs consisted of seven mucosal excisions with plication of the rectal wall, seven anal canal narrowings, and 19 perineal proctosigmoidectomies. The transabdominal repairs included 12 rectopexies, six sigmoidectomies with rectopexy, two sigmoidectomies or low anterior resections, and five laparoscopic ventral mesh rectopexies. The patients were predominantly elderly and female. Surgeons tended to select the transperineal approach for patients with multimorbidity (P = 0.028) and those requiring urgent (unplanned) surgery (P = 0.004). The transperineal approach was associated with a significantly shorter operative time by approximately 20 min (P = 0.007), with comparable blood loss between the two groups (P = 0.818).

Click to view | Table 1. Baseline Characteristic of all Patients |

Outcomes were similar between the two approaches in the univariable analysis, with comparable complication rates. Three complications were identified: one case of prolonged 6-month anal pain in the transabdominal group (following sigmoidectomy with rectopexy) and two complications in the transperineal group (both following the Altemeier procedure): an acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease requiring prolonged intubation and a ureter injury necessitating percutaneous nephrostomy followed by surgical reconstruction. No deaths occurred among the eligible patients. However, one death from pneumonia following rectal prolapse surgery was recorded but excluded from the study because the prolapse was secondary to rectal cancer.

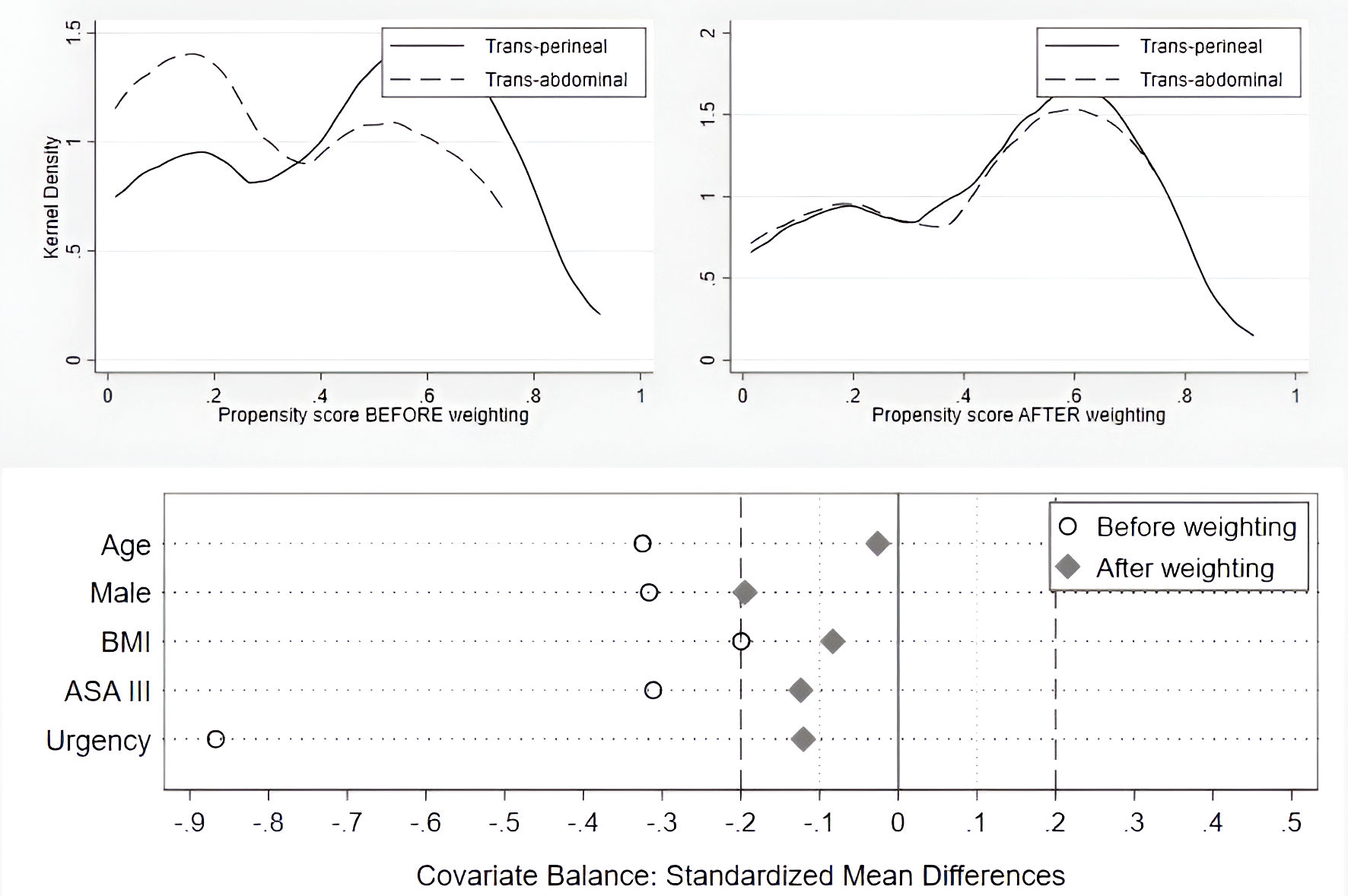

Comparative outcomes using propensity score weighting are presented in Table 2. Covariate balance was assessed using mean standardized differences and kernel density plots, as shown in Figure 2. After weighting, the mean standardized differences were reduced but remained slightly elevated (above 10%), though within the acceptable range of 10-25% [16]. The kernel density plot showed improved overlap of propensity score distributions after weighting compared to before weighting.

Click to view | Table 2. Comparative Outcomes Between Transperineal and Transabdominal Complete Rectal Prolapse Repair With Inverse Probability Weighting Propensity Score Analysis |

Click for large image | Figure 2. Covariate balance evaluation before and after propensity score weighting using inverse probability weighting: Kernel density plot (above) and mean standardized differences (below). “Urgency” refers to any surgical procedure for rectal prolapse performed on a nonelective basis. ASA: American society of anesthesiology; BMI: body mass index. |

Regarding the main outcomes, both approaches had similar complication and recurrence rates, with risk ratios (95% confidence interval (CI)) of 0.67 (0.06, 7.65) and 0.62 (0.11, 3.53), respectively. These results suggest a trend toward lower complication and recurrence rates with the transabdominal approach. The incidence of constipation and fecal incontinence was also comparable, though fecal incontinence tended to be lower in the transabdominal group (risk ratio (95% CI): 0.59 (0.23, 1.57)). The length of hospital stay was similar between the two groups, with a difference of approximately 0.02 days.

Sensitivity analyses, detailed in Table 2, supported these findings. When excluding patients with less than 1 year of follow-up (18 transperineal vs. 16 transabdominal, 24 exclusions), the outcomes remained comparable between the two groups. However, the trend favoring the transabdominal approach for lower complications and recurrence disappeared. Additionally, the transabdominal approach showed a nonsignificant trend toward higher constipation rates (risk ratio (95% CI): 2.24 (0.61, 8.19)) but continued to suggest a lower rate of fecal incontinence (risk ratio (95% CI): 0.50 (0.16, 1.60)). In the second sensitivity analysis, which replaced ASA III status with the multimorbidity variable (two or more comorbidities), the outcome comparisons were consistent with the full model (58 patients, irrespective of complete 1-year follow-up).

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Our study results showed comparable outcomes regarding recurrence and early complications between abdominal and perineal complete rectal prolapse repair. For recurrence, our main results aligned with an observational study and a meta-analysis of clinical trials [15, 17]. However, some studies suggested a lower recurrence rate with the abdominal approach, and our results also showed a trend favoring a lower recurrence rate for this procedure [18, 19]. When accounting for adequate follow-up time, the trend of reduced recurrence was diminished.

Studies, including ours, showed comparable early complications between the two techniques [19-21]. Regarding late complications, our results were consistent with various published studies indicating that the abdominal approach was associated with less fecal incontinence [15], though this finding was not statistically significant. When patients were adequately followed up (at least 1 year), the transabdominal approach was also associated with a trend of increasing constipation (though not statistically significant), which was consistent with other studies [15].

Overall, based on our findings and previously published studies, transabdominal rectal prolapse repair may be associated with lower recurrence and comparable early complications. However, it might offer less fecal incontinence at the cost of higher constipation.

Transperineal rectal prolapse repairs also have beneficial properties. Their main advantage is that they are less invasive procedures that can be performed under regional anesthesia, especially for very frail or bedridden patients [21]. Our department’s surgeons followed this practice, as reflected in our data, where patients with multimorbidity were more likely to undergo the transperineal approach. Many studies, including ours, revealed acceptable results with potentially comparable recurrence rates [15, 17, 21].

However, rectal prolapse is a rare condition. During the 10-year cohort, our institute surgically repaired this condition in only 58 cases. With this rarity, achieving a learning curve for specific rectal prolapse repair procedures is challenging [22], even in referral institutes, as referring such patients is often impractical due to their age and need for assistance [23]. This limitation in the learning curve was reflected in our data: although the transperineal approach is less invasive, unusual complications can occur due to a lack of familiarity with the procedure, as seen in one case of ureteral injury during a transperineal proctosigmoidectomy in our data.

Following this direction, and regarding clinical implications, the choice of rectal prolapse repair should be based on the specific condition of each patient. For example, in frail, bedridden, or less-prepared patients (urgent cases), the transperineal approach might be more suitable, as it is less invasive and offers acceptable (sometimes comparable) outcomes. On the other hand, for healthier patients, the transabdominal approach may be more appropriate, as it is associated with a lower recurrence rate. Additionally, the recently introduced laparoscopic approach, which reduces the invasiveness of the transabdominal technique, has shown promising results in some published studies [21, 24, 25]. Furthermore, regarding clinical applications based on specific presentations, rectal prolapse patients with significant preoperative constipation may benefit from the perineal approach, as it is associated with less postoperative constipation and improved bowel movement frequency [15, 26], potentially due to a reduction in rectal capacity and compliance [27]. On the other hand, patients whose primary symptom is fecal incontinence may achieve greater benefit from the abdominal approach, as it is generally associated with lower rates of postoperative incontinence [25, 28]. Nevertheless, both surgical approaches have been reported to improve symptoms of constipation and fecal incontinence to varying degrees [6, 15, 28]. Further research, particularly on long-term functional outcomes, is needed. Until more conclusive data are available, surgeons should base their decisions on experience, proficiency, and patient-specific factors when selecting the most appropriate surgical technique.

Our study had strengths, reflecting real-world practice in a regional service hospital over a long period (14 years). We believe that our results add valuable knowledge regarding rectal prolapse repair methods and may indirectly assist surgeons in regional service areas in selecting the optimal approach.

Our study, however, had some limitations that need to be declared. First, our data had a limited sample size due to the rarity of the condition. Only 58 eligible patients were included in our final analysis, which may limit various aspects of the outcomes, particularly the generalizability to broader applications. However, our cohort covered a period of 14 years, and we believe that our results provide insight into rectal prolapse repairs. Second, a large proportion of our patients did not meet the adequate follow-up period. To our knowledge, no specific follow-up period criteria have been established for rectal prolapse. However, a large study on rectal prolapse revealed that the median time to recurrence after surgery was 21.9 months [29], and one meta-analysis suggested that adequate follow-up should be at least 1 year [15]. We then conducted a sensitivity analysis regarding this issue. Although the sensitivity analysis results were comparable to the full model, it detected a shifting trend, suggesting that the transabdominal approach might not be superior regarding the recurrence rate. While transabdominal repair showed a trend toward lower fecal incontinence, when patients were adequately followed up, the trend toward higher constipation was also observed in the transabdominal group. These changing trends required adequate follow-up time to be revealed. Nevertheless, rectal prolapse patients are prone to loss to follow-up, as they are typically extremely elderly and require assistance from caregivers. During patient data collection, we attempted to assess patient status and found that a significant proportion of patients had passed away, likely due to the extended inclusion period of the study (14 years) and the nature of the disease. Consequently, complete and adequate follow-up for all patients was not feasible. Third, while rectal prolapse repair surgeries are generally categorized into transabdominal and transperineal approaches, many technical details can impact outcomes. For example, considerations include the use of mesh, whether to resect parts of the sigmoid colon or rectum, the various methods of rectal fixation or rectopexy [1, 4, 6], and specific details of various procedures, such as the instruments used for exposure, among others. All of these factors can influence outcomes, particularly recurrence rates. These variations were often not recorded and, therefore, could not be evaluated. Moreover, comparing procedures with vastly different levels of invasiveness posed a challenge, ranging from minimally invasive techniques performed under local anesthesia, such as the Thiersch procedure, to highly invasive procedures, such as colorectal resection. Therefore, our study provides a broad overview of rectal prolapse repair rather than an in-depth analysis of specific techniques. Fourth, regarding the diagnosis of constipation and fecal incontinence using the Rome IV criteria, to our knowledge, no established criteria exist specifically for postoperative constipation or fecal incontinence. Since the Rome IV criteria are designed for functional conditions, it may be more appropriate to use scoring systems such as the Agachan-Wexner or Jorge-Wexner scores, which are more commonly utilized in rectal prolapse studies [9, 30, 31]. Lastly, there were limitations regarding the study methodology. Retrospective data collection and observational studies have inherent limitations regarding bias control, especially in outcome clarification [32]. The attending physician may have recorded results favoring their preferred approach, particularly in relation to fecal incontinence and constipation outcomes. Missing data are another limitation of retrospective studies. Although propensity score analysis is designed to address unbalanced confounders, it cannot account for unknown or unmeasured confounders. Thus, our results should be interpreted alongside findings from larger, higher-level evidence-based studies (e.g., meta-analyses).

In conclusion, transabdominal rectal prolapse repair was associated with a trend toward lower recurrence and lower fecal incontinence compared to transperineal repair. If patients had adequate 1-year follow-up, transabdominal repair possibly showed higher constipation. However, our comparative results did not reach statistical significance, and statistically, both techniques had comparable recurrence, early, and long-term complications. Surgeons should choose the approach according to patients’ status, with acceptable results from both approaches.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

The authors received no financial support.

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

The requirement for patient consent was waived due to the retrospective study design and use of deidentified data.

Author Contributions

All authors (PK, ST, TS, and BC) made substantial contributions to this manuscript. All authors conceived and designed the study. PK and ST were responsible for the statistical analysis. All authors participated in drafting the manuscript, critically revising it, and approving the final version.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to restrictions (they are containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants).

Abbreviations

ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; CI: confidence interval

| References | ▴Top |

- Bordeianou L, Hicks CW, Kaiser AM, Alavi K, Sudan R, Wise PE. Rectal prolapse: an overview of clinical features, diagnosis, and patient-specific management strategies. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18(5):1059-1069.

doi pubmed - Kairaluoma MV, Kellokumpu IH. Epidemiologic aspects of complete rectal prolapse. Scand J Surg. 2005;94(3):207-210.

doi pubmed - Oruc M, Erol T. Current diagnostic tools and treatment modalities for rectal prolapse. World J Clin Cases. 2023;11(16):3680-3693.

doi pubmed - Joubert K, Laryea JA. Abdominal approaches to rectal prolapse. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2017;30(1):57-62.

doi pubmed - Fleming FJ, Kim MJ, Gunzler D, Messing S, Monson JR, Speranza JR. It's the procedure not the patient: the operative approach is independently associated with an increased risk of complications after rectal prolapse repair. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14(3):362-368.

doi pubmed - Gallo G, Martellucci J, Pellino G, Ghiselli R, Infantino A, Pucciani F, Trompetto M. Consensus Statement of the Italian Society of Colorectal Surgery (SICCR): management and treatment of complete rectal prolapse. Tech Coloproctol. 2018;22(12):919-931.

doi pubmed - Harrison C, Fortin M, van den Akker M, Mair F, Calderon-Larranaga A, Boland F, Wallace E, et al. Comorbidity versus multimorbidity: Why it matters. J Multimorb Comorb. 2021;11:2633556521993993.

doi pubmed - Cannon JA. Evaluation, diagnosis, and medical management of rectal prolapse. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2017;30(1):16-21.

doi pubmed - Drossman DA, Chang L, Chey WD, Lembo AJ, Simren M, Whitehead WE, eds. Rome IV: Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders - Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction. Raleigh, NC: Rome Foundation. 2016.

- Ahmad NZ, Stefan S, Adukia V, Naqvi SAH, Khan J. Laparoscopic ventral mesh rectopexy: functional outcomes after surgery. Surg J (N Y). 2018;4(4):e205-e211.

doi pubmed - Franchetti Y. Use of propensity scoring and its application to real-world data: advantages, disadvantages, and methodological objectives explained to researchers without using mathematical equations. J Clin Pharmacol. 2022;62(3):304-319.

doi pubmed - Sendor R, Sturmer T. Core concepts in pharmacoepidemiology: confounding by indication and the role of active comparators. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2022;31(3):261-269.

doi pubmed - Shiba K, Kawahara T. Using propensity scores for causal inference: pitfalls and tips. J Epidemiol. 2021;31(8):457-463.

doi pubmed - Austin PC. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat Med. 2009;28(25):3083-3107.

doi pubmed - Pellino G, Fuschillo G, Simillis C, Selvaggi L, Signoriello G, Vinci D, Kontovounisios C, et al. Abdominal versus perineal approach for external rectal prolapse: systematic review with meta-analysis. BJS Open. 2022;6(2):zrac018.

doi pubmed - Stuart EA, Lee BK, Leacy FP. Prognostic score-based balance measures can be a useful diagnostic for propensity score methods in comparative effectiveness research. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(8 Suppl):S84-S90.e81.

doi pubmed - Chung JS, Ju JK, Kwak HD. Comparison of abdominal and perineal approach for recurrent rectal prolapse. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2023;104(3):150-155.

doi pubmed - Riansuwan W, Hull TL, Bast J, Hammel JP, Church JM. Comparison of perineal operations with abdominal operations for full-thickness rectal prolapse. World J Surg. 2010;34(5):1116-1122.

doi pubmed - Emile SH, Khan SM, Garoufalia Z, Silva-Alvarenga E, Gefen R, Horesh N, Freund MR, et al. A network meta-analysis of surgical treatments of complete rectal prolapse. Tech Coloproctol. 2023;27(10):787-797.

doi pubmed - Mustain WC, Davenport DL, Parcells JP, Vargas HD, Hourigan JS. Abdominal versus perineal approach for treatment of rectal prolapse: comparable safety in a propensity-matched cohort. Am Surg. 2013;79(7):686-692.

pubmed - Young MT, Jafari MD, Phelan MJ, Stamos MJ, Mills S, Pigazzi A, Carmichael JC. Surgical treatments for rectal prolapse: how does a perineal approach compare in the laparoscopic era? Surg Endosc. 2015;29(3):607-613.

doi pubmed - Nacion AJD, Park YY, Kim HS, Yang SY, Kim NK. Surgical treatment of rectal prolapse: a 10-year experience at a single institution. J Minim Invasive Surg. 2019;22(4):164-170.

doi pubmed - Finn CB, Wirtalla C, Mascuilli T, Krumeich LN, Wachtel H, Fraker D, Kelz RR. Simulated data-driven hospital selection for surgical treatment of well-differentiated thyroid cancer in older adults. Surgery. 2023;173(1):207-214.

doi pubmed - Hajibandeh S, Hajibandeh S, Arun C, Adeyemo A, McIlroy B, Peravali R. Meta-analysis of laparoscopic mesh rectopexy versus posterior sutured rectopexy for management of complete rectal prolapse. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2021;36(7):1357-1366.

doi pubmed - Emile SH, Elfeki H, Shalaby M, Sakr A, Sileri P, Wexner SD. Outcome of laparoscopic ventral mesh rectopexy for full-thickness external rectal prolapse: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression analysis of the predictors for recurrence. Surg Endosc. 2019;33(8):2444-2455.

doi pubmed - Olatunbode O, Rangarajan S, Russell V, Viswanath Y, Reddy A. A quantitative study to explore functional outcomes following laparoscopic ventral mesh rectopexy for rectal prolapse. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2022;104(6):449-455.

doi pubmed - Ris F, Colin JF, Chilcott M, Remue C, Jamart J, Kartheuser A. Altemeier's procedure for rectal prolapse: analysis of long-term outcome in 60 patients. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14(9):1106-1111.

doi pubmed - Al Zangana I, Al-Taie RH, Al-Badri S, Ismail M. Rectal prolapse surgery: balancing effectiveness and safety in abdominal and perineal approaches. Cureus. 2024;16(9):e69868.

doi pubmed - Hong KD, Hyun K, Um JW, Yoon SG, Hwang DY, Shin J, Lee D, et al. Clinical outcomes of surgical management for recurrent rectal prolapse: a multicenter retrospective study. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2022;102(4):234-240.

doi pubmed - Agachan F, Chen T, Pfeifer J, Reissman P, Wexner SD. A constipation scoring system to simplify evaluation and management of constipated patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39(6):681-685.

doi pubmed - de la Portilla F, Calero-Lillo A, Jimenez-Rodriguez RM, Reyes ML, Segovia-Gonzalez M, Maestre MV, Garcia-Cabrera AM. Validation of a new scoring system: Rapid assessment faecal incontinence score. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;7(9):203-207.

doi pubmed - Talari K, Goyal M. Retrospective studies - utility and caveats. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2020;50(4):398-402.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Gastroenterology Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.