| Gastroenterology Research, ISSN 1918-2805 print, 1918-2813 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, Gastroenterol Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://gr.elmerpub.com |

Original Article

Volume 18, Number 3, June 2025, pages 108-118

Statins and the Risk of Colorectal Cancer in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Joelle Sleimana, f , Malek Kreidiehb, Un Jung Leec, Peter Khourid, Brendan Plann-Curleye, Cristina Sisonc, Liliane Deebb

aDepartment of Internal Medicine, Staten Island University Hospital, Northwell Health, Staten Island, NY, USA

bDivision of Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, Staten Island University Hospital, Northwell Health, Staten Island, NY, USA

cBiostatistics Unit, Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research, Northwell Health, Manhasset, NY, USA

dDepartment of Internal Medicine, SUNY Downstate Health Sciences University, Brooklyn, NY, USA

eNorthwell, New Hyde Park, NY and Medical Library, Staten Island University Hospital, Staten Island, NY, USA

fCorresponding Author: Joelle Sleiman, Department of Internal Medicine, Staten Island University Hospital, Northwell Health, Staten Island, NY, USA

Manuscript submitted February 20, 2025, accepted May 24, 2025, published online June 4, 2025

Short title: Statins and CRC Risk in IBD Patients

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/gr2028

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Statins are reported to reduce colorectal cancer (CRC) risk in the general population, but their effect on individuals with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) remains uncertain. We aimed to evaluate the relationship between statin use and CRC risk in patients with IBD.

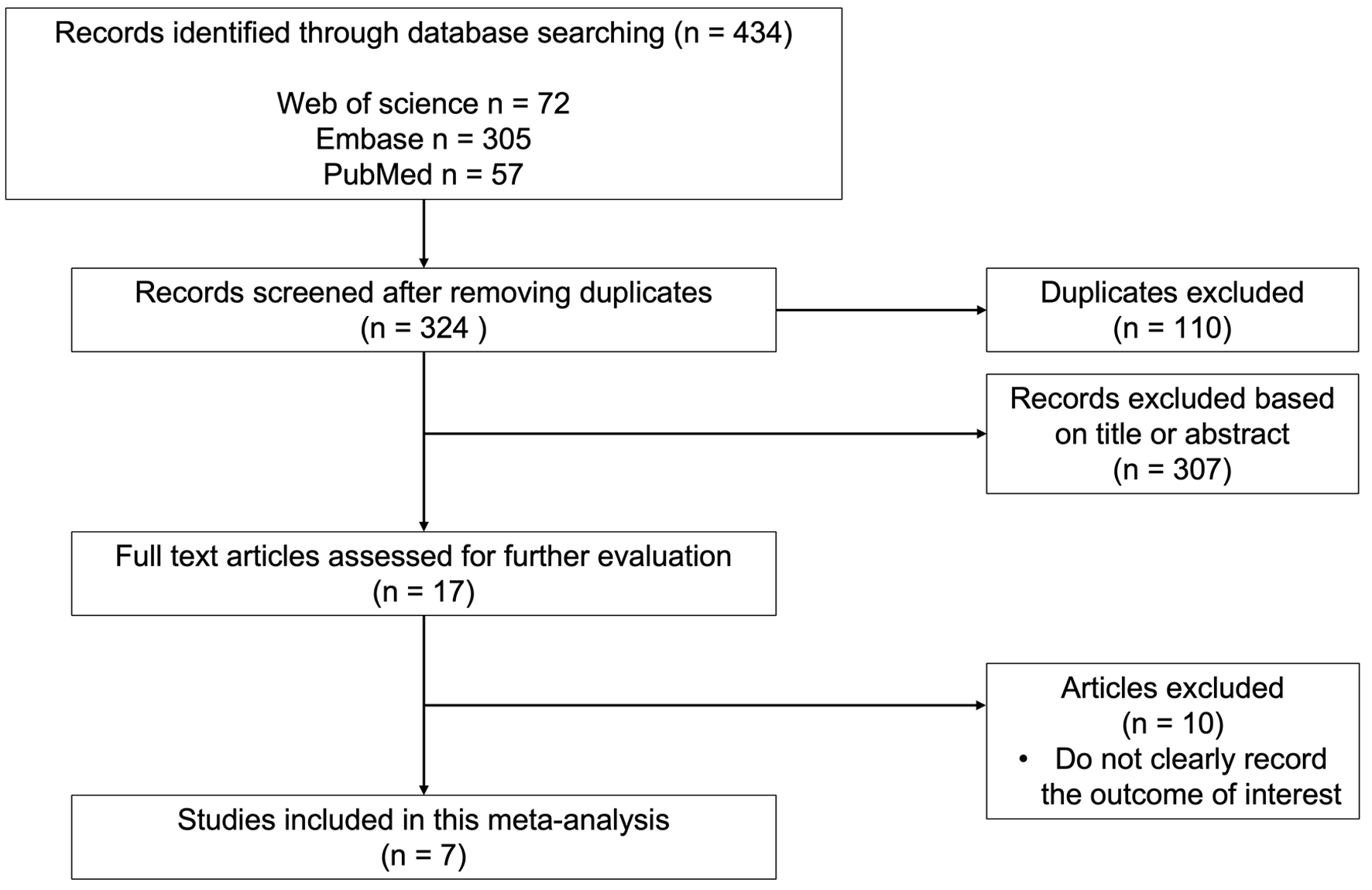

Methods: A comprehensive review of the literature was conducted on PubMed, Web of Science, and EMBASE to evaluate the association between statin use and the development of CRC in patients with IBD. After deduplication, there were 324 studies screened, and those reporting odds ratios (ORs) or hazard ratios (HRs) for CRC risk in IBD patients using statins were included. The primary endpoints included the development of CRC (OR) and time to CRC (HR). A meta-analysis utilizing fixed or random-effects models, heterogeneity tests, and a funnel plot was performed in R (version 4.3.0) with alpha of 0.05.

Results: This meta-analysis included seven studies involving 59,596 patients: three for OR (11,116 patients) and four for HR (48,480 patients). The pooled OR was 0.22 (95% confidence interval (CI): 0.01 - 7.81), suggesting 78% lower odds of CRC in statin users, though not statistically significant (P = 0.21), with potential publication bias. The pooled HR was 0.77 (95% CI: 0.63 - 0.94), indicating a significant 23% reduction in CRC hazard for statin users (P < 0.05), with low publication bias.

Conclusion: Our meta-analysis showed that statin use is associated with a reduced risk of CRC in IBD, significant in HR-based but not in OR-based analysis. Large randomized controlled trials are needed to clarify the duration of statin use and their chemopreventive effects, independent of factors such as targeted therapy for chronic mucosal inflammation.

Keywords: Statins; Colorectal cancer; Inflammatory bowel disease; Odds ratio; Hazard ratio

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic gastrointestinal disease characterized by chronic inflammation of the digestive tract in a relapsing and remitting manner [1]. The two primary forms of IBD are ulcerative colitis (UC), which impacts solely the colon, and Crohn’s disease (CD), which may affect the whole gastrointestinal system [2]. Patients with IBD face a higher risk of developing colorectal cancer (CRC). The chronic inflammation of the mucosa in IBD patients triggers and promotes tumorigenesis, resulting in an inflammation, dysplasia, and carcinoma sequence rather than the adenoma carcinoma sequence typically observed in sporadic cases of CRC. The likelihood of developing CRC in this group varies based on the duration of the disease, age at diagnosis, and extent of inflammation [3]. Given that chronic inflammation may play an important role in the pathogenesis of CRC in this specific population, controlling this inflammation could decrease the potential risk of developing CRC; hence, it is important to develop chemopreventive agents to control mucosal inflammation and potentially prevent CRC development in this high-risk population [4].

Statins, known as 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase inhibitors, are lipid-lowering medications prescribed worldwide for their effectiveness in reducing mortality from cardiovascular disease. In addition to their role in inhibiting cholesterol biosynthesis, statins also exhibit anti-inflammatory, pro-apoptotic, anti-proliferative, and anti-neoplastic properties [5]. Given their modulation of these pathways, research has focused on the association between statins and CRC, exploring the potential of statins as chemopreventive agents for CRC.

Several meta-analyses and systematic reviews have shown that statins lower the risk of CRC development in the general population [6-9]. Recent studies have explored the relationship between statin use and CRC development in patients with IBD, a high-risk population for CRC. However, this benefit in this specific population is still under investigation and remains inconclusive to this day. To our knowledge, the literature lacks high-impact studies, such as meta-analyses and randomized controlled trials (RCTs), that focus specifically on the effect of statins on CRC development in IBD patients. This underscores the importance of summarizing the evidence to gain a clearer understanding of the role of statins in preventing the development of CRC in patients with IBD.

The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to offer a thorough summary and further assess the relationship between statin therapy and the likelihood of developing CRC in patients with IBD.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

Systematic search

Two investigators (BPC and JS) conducted a systematic literature search for all relevant articles regarding the effects of statins on CRC development in patients with IBD. The databases PubMed, EMBASE, and Web of Science were searched from their inception up to September 4, 2024, utilizing the following primary keywords: “Inflammatory Bowel Diseases” OR “Inflammatory Bowel Disease” OR IBD OR IBDs OR “Ulcerative Colitis” OR UC OR “Crohn Disease” OR “Crohn’s Disease” OR “Colitis, Ulcerative” OR “ulcerative colitis” OR “chronic colitis” OR “inflammatory colitis” AND colon OR colorectal OR rectal OR anal OR carcinoma OR tumor OR neoplasia OR dysplasia OR adenoma OR cancer OR neoplasm OR carcinoma OR tumor OR tumour OR adenoma OR “Colorectal Neoplasms” OR “colon cancer” OR “Colorectal cancer” OR “colon neoplasm” OR “colorectal neoplasm” AND “Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA Reductase Inhibitors” OR “HMG CoA” OR statin OR “Hypercholesterolemia drug therapy” OR “hypocholesterolemic agent” OR Lipitor OR fluvastatin OR lescol OR lovastatin OR Altoprev OR pitavastatin OR Livalo OR pravastatin OR rosuvastatin OR crestor OR simvastatin OR zocor. Supplementary Material 1 (gr.elmerpub.com) shows the librarian’s complete search strategy.

Eligibility criteria

A total of 324 studies were screened after deduplication. Included studies were full-text articles that assessed the relationship between statin use and CRC in patients with IBD, providing either an odds ratio (OR) or a hazard ratio (HR) along with the relevant 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). Studies were excluded if they failed to meet the inclusion criteria outlined above, or if they were classified as reviews, letters, editorials, conference abstracts, case reports, or animal trials.

Data extraction

The primary endpoints were the development of CRC (OR) and time to CRC (HR). The data gathered from each study include the first author’s name, year of study, study design, study region, total patient counts for both statin and non-statin groups, duration of statin use (if available), follow-up period, risk estimates (OR/HR), and the corresponding 95% CIs. HRs were derived from the multivariable model. Any disagreements regarding study selection and data extraction were resolved through discussions among the co-authors until a consensus was reached.

Statistical analysis

A meta-analysis was conducted to estimate the overall effect of the primary outcome, OR or HR. A test for heterogeneity between studies under the null hypothesis of no heterogeneity was performed using the DerSimonian-Laird method. A random-effects model was used to pool the effect size if there was a considerable between-study heterogeneity. If between-study heterogeneity was minimal, we employed a fixed-effects model to pool the effect size. Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic, which indicates the proportion of total variation among studies attributed to heterogeneity rather than random chance. An I2 value of 50% or greater was deemed as substantial heterogeneity. A funnel plot was created to evaluate publication bias. The level of significance was set at 5%. All analyses were performed using R language (version 4.3.0).

| Results | ▴Top |

Search results

Figure 1 presents a detailed flow chart summarizing the study selection process. A total of 434 articles were found in the initial search (PubMed: n = 57; EMBASE: n = 305; Web of Science: n = 72). Upon eliminating duplicates and examining the titles and abstracts, 417 were deemed ineligible. After conducting a full-text screening of the remaining 17 articles, seven studies were suitable for the meta-analysis. The studies included in the meta-analysis were published between 2005 and 2023.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Detailed flow diagram of study selection process. |

Study characteristics and quality assessment

All seven studies included in the analysis were retrospective cohort studies. Two studies were conducted in the United States of America, two in Israel, one in Sweden, one in China, and one in South Korea. Table 1 [10-16] displays the characteristics of all included studies.

Click to view | Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Included Studies Investigating CRC Development in Patients Using Statins |

Overall analysis

Seven studies involving 59,596 patients were eligible for this meta-analysis: three studies for OR (11,116 patients) and four studies for HR (48,480 patients).

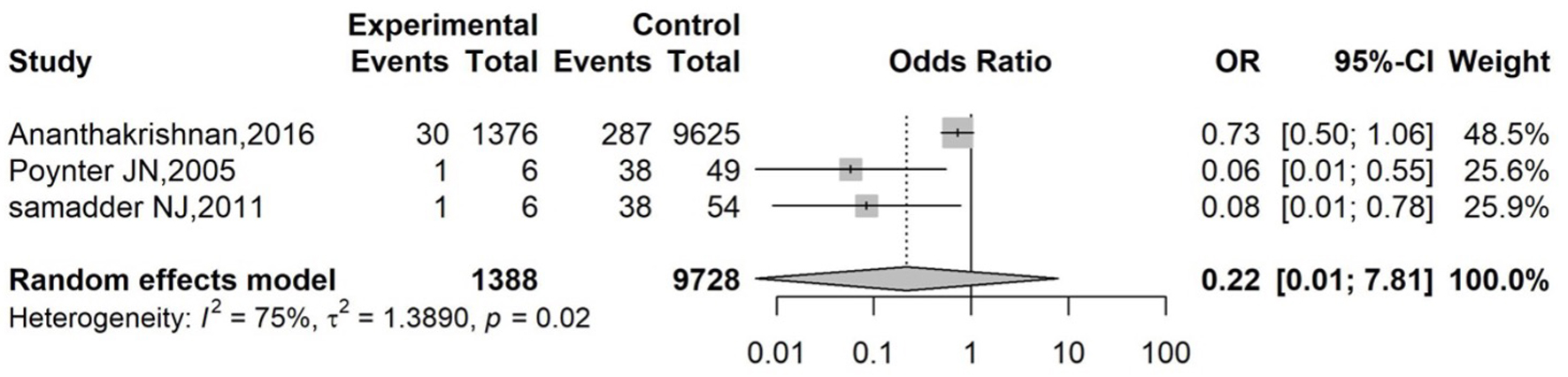

OR

The OR of each study with its associated 95% CI, the heterogeneity test, and the overall OR for all studies is reported in Figure 2. The pooled effect size, based on the random-effects model (P = 0.02 and I2 = 75%), is OR = 0.22 (95% CI: 0.01 - 7.81). The pooled effect indicates that the odds of developing CRC in patients exposed to statins was 78% lower than in those who were not exposed to statins. However, the result was not significant (P = 0.21).

Click for large image | Figure 2. Forest plot of overall effect for OR. Forest plot of pooled ORs and 95% CIs from three studies evaluating the association between statin use and colorectal cancer risk in IBD patients. The diamond represents the overall random-effects model (OR: 0.22; 95% CI: 0.01 - 7.81; P = 0.02; I2 = 75%). CI: confidence interval; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; OR: odds ratio. |

The presence of publication bias, as indicated by the asymmetry of the funnel plot, is illustrated in Figure 3. The presence of two studies with high standard errors in the lower left section of the funnel plot indicates a potential publication bias. Egger’s regression test is commonly used to assess asymmetry in a funnel plot. However, it could not be performed as it requires at least 10 studies.

Click for large image | Figure 3. Funnel plot to evaluate for publication bias (odds ratio). Funnel plot assessing publication bias among studies included in the odds ratio analysis. Each dot represents an individual study. |

HR

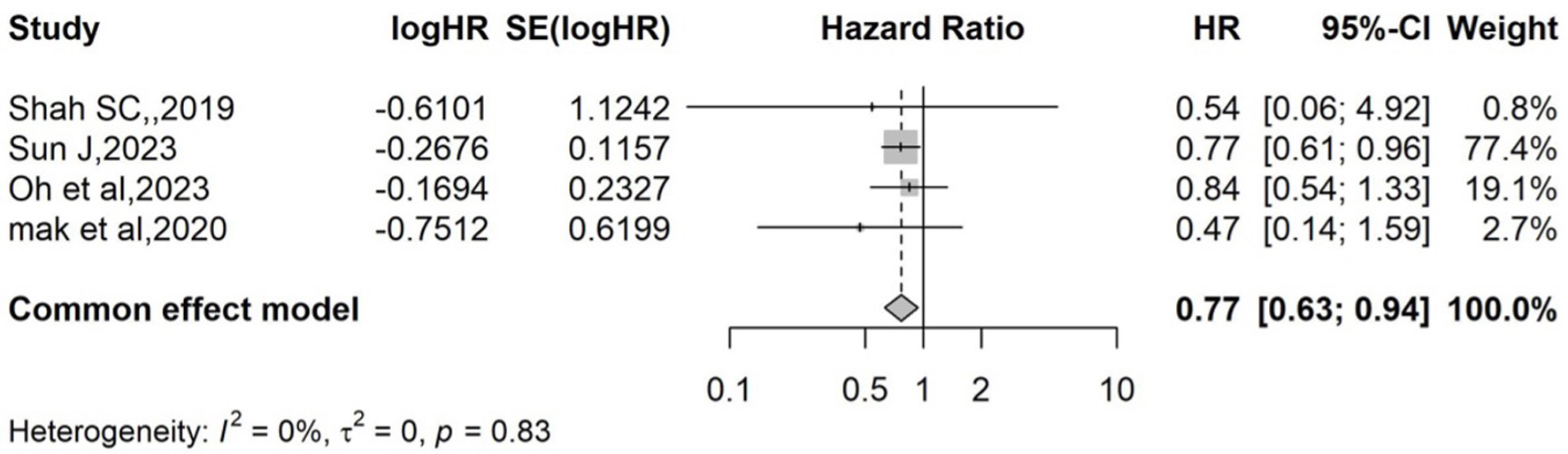

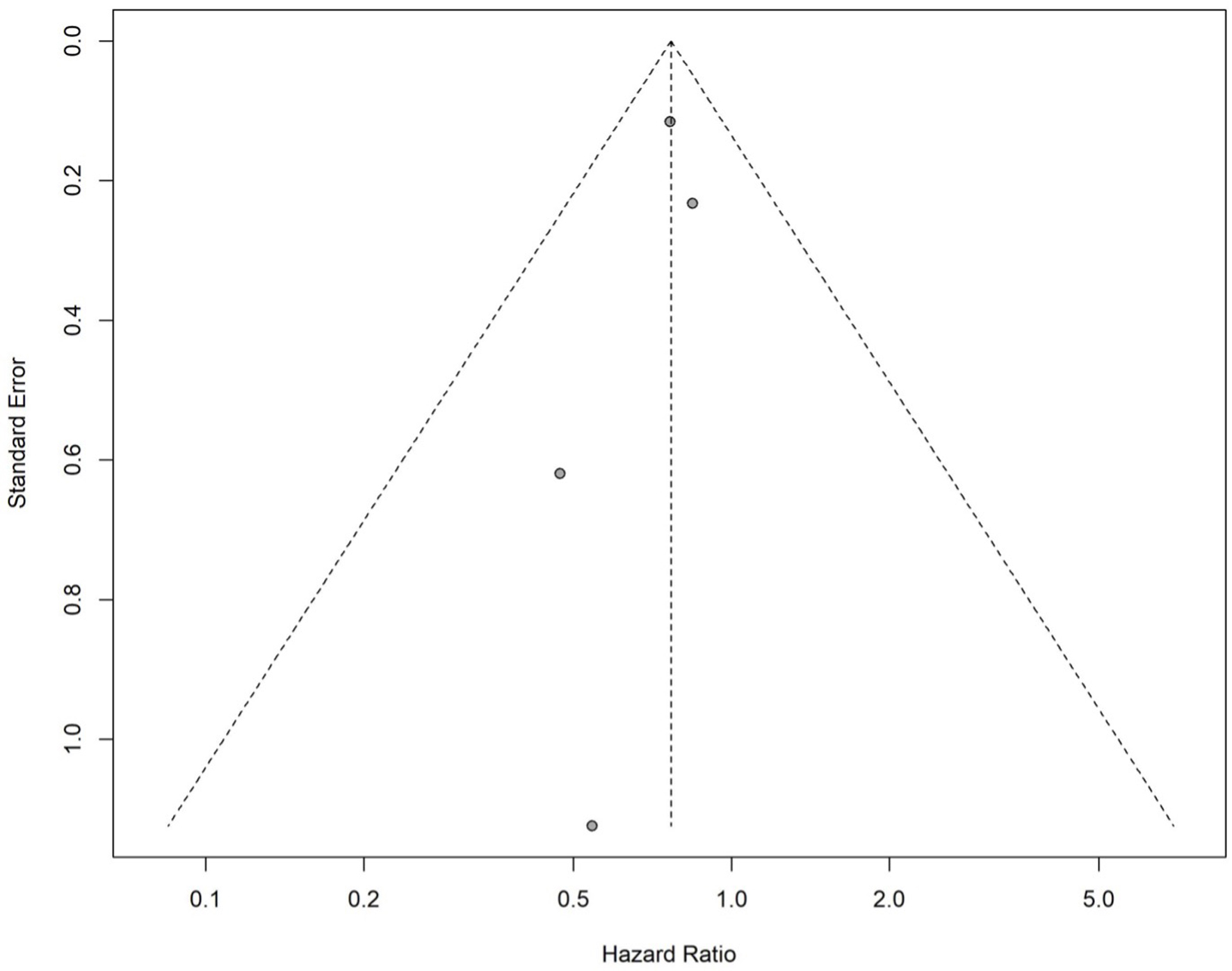

The HR of each study with its associated 95% CI, the heterogeneity test, and the overall HR for all studies is reported in Figure 4. The pooled effect size, based on the common-effect model (P = 0.78 and I2 = 0%), is HR = 0.77 (95% CI: 0.63 - 0.94). The pooled HR indicates that the likelihood of developing CRC is 23% lower in those with statin exposure than in those without statin exposure. This association was statistically significant (P < 0.05). Figure 5 shows a symmetric funnel plot, which suggests no evidence of publication bias. Egger’s regression test, used to assess symmetry, could not be conducted because the test requires at least 10 studies.

Click for large image | Figure 4. Forest plot of overall effect for HR. Forest plot displaying individual and pooled HRs with 95% CIs for the association between statin use and colorectal cancer risk in IBD patients. The pooled effect size, based on the common-effect model (P = 0.78 and I2 = 0%), is HR = 0.77 (95% CI: 0.63 - 0.94). CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease. |

Click for large image | Figure 5. Funnel plot to evaluate for publication bias (hazard ratio). Funnel plot assessing publication bias in studies reporting hazard ratios for colorectal cancer risk in inflammatory bowel disease patients on statins. Each dot represents a study. |

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analyses were conducted based on IBD type - CD and UC - to further investigate the association between statin use and CRC development. These analyses aimed to determine whether the protective effect of statins varied across different types of IBD.

UC

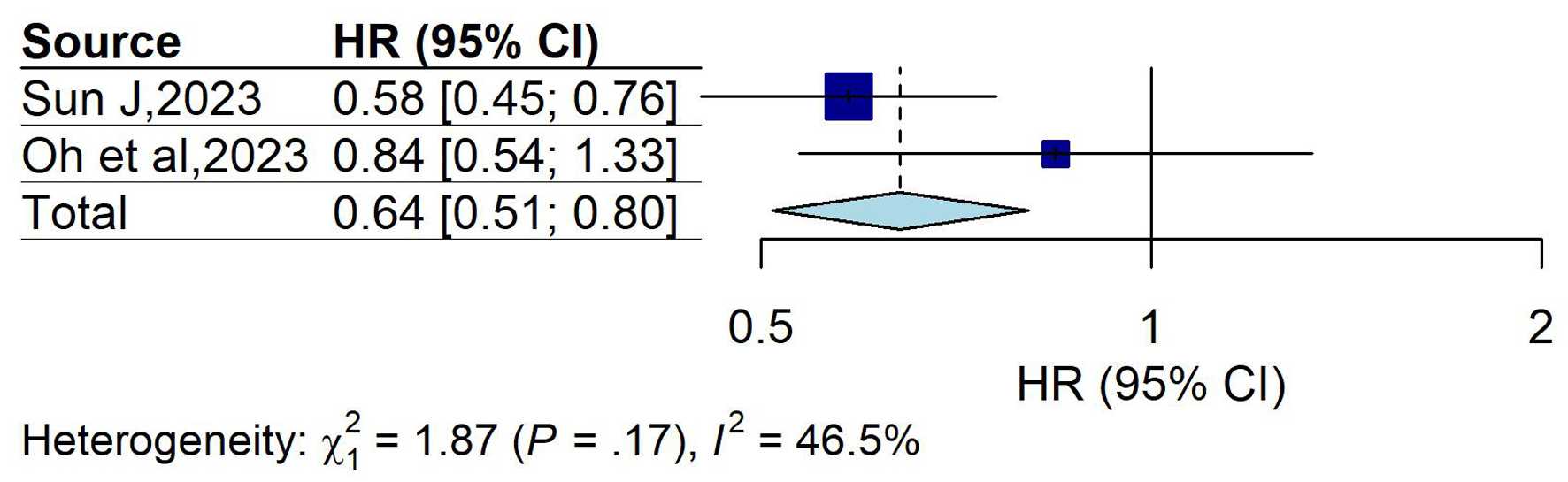

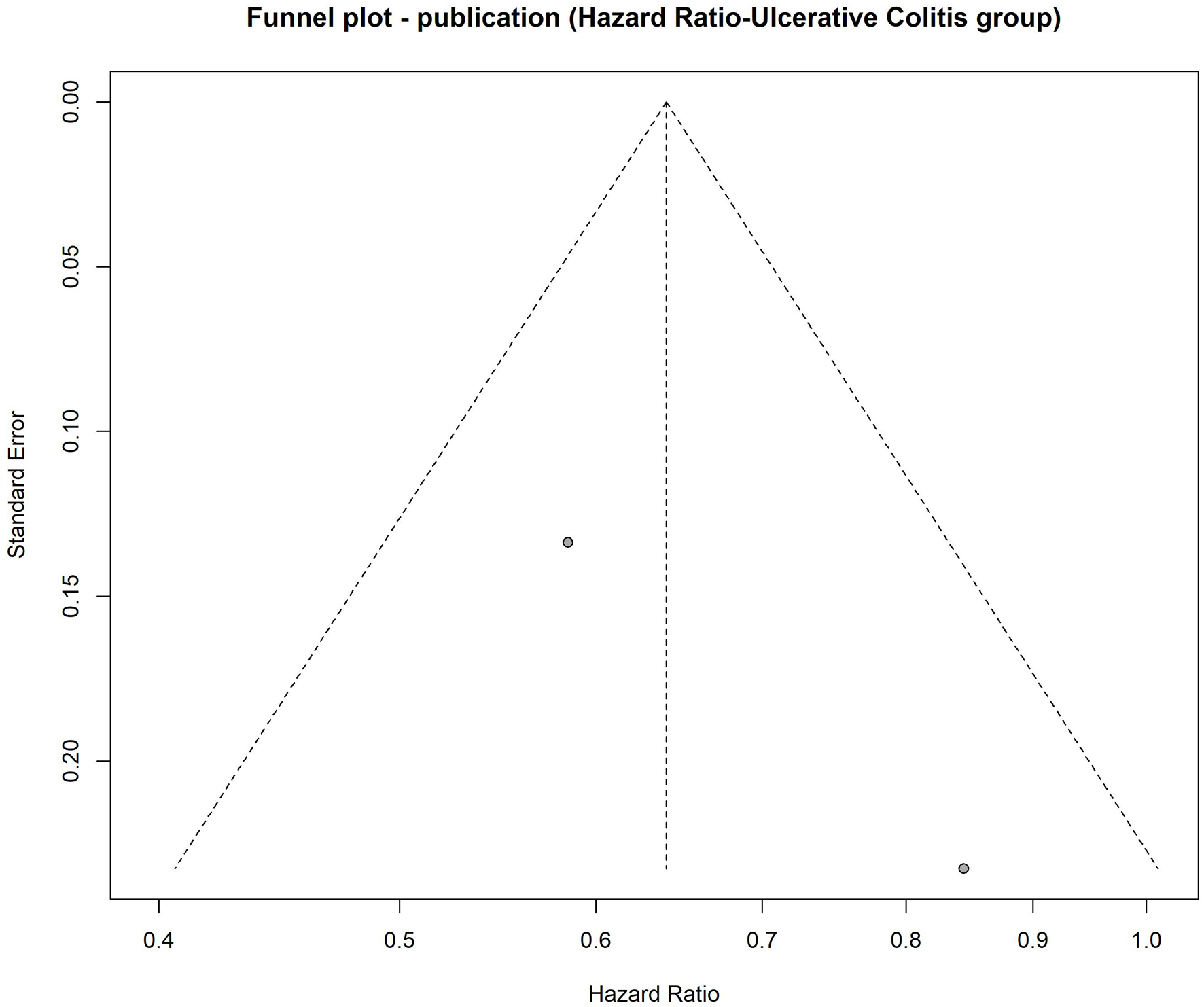

The subgroup analysis based on ORs could not be performed for patients with UC, as only one study was available in this subgroup (OR = 1.01; 95% CI: 0.65 - 1.56; P = 0.98). Alternatively, the subgroup analysis based on HRs included two studies. The pooled effect size, calculated using a common-effect model (P = 0.17; I2 = 46.5%), was HR = 0.64 (95% CI: 0.51 - 0.80), indicating a statistically significant 36% reduction in CRC risk among patients with UC exposed to statins (P < 0.05) (Fig. 6). The funnel plot appeared symmetric, suggesting no evidence of publication bias (Fig. 7). Egger’s regression test could not be conducted due to the inclusion of fewer than 10 studies.

Click for large image | Figure 6. Forest plot of overall effect (HR) in ulcerative colitis group. Forest plot showing pooled HRs with 95% CIs for the association between statin use and colorectal cancer risk in patients with ulcerative colitis. The overall HR was 0.64 (95% CI: 0.51 - 0.80), suggesting a protective effect. Moderate heterogeneity was observed (I2 = 46.5%; P = 0.17). CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio. |

Click for large image | Figure 7. Funnel plot to evaluate publication bias for hazard ratio in ulcerative colitis group. Funnel plot assessing publication bias among studies evaluating the association between statin use and colorectal cancer risk in ulcerative colitis patients. |

CD

The subgroup analyses for patients with CD could not be pooled, as only one study was available for each effect measure group. The single OR estimate was OR = 0.36 (95% CI: 0.16 - 0.81; P = 0.01), suggesting a statistically significant reduction in CRC risk among statin users. The single HR estimate was HR = 2.00 (95% CI: 0.96 - 4.15; P = 0.06), which did not reach statistical significance. Due to the inclusion of only one study per outcome, heterogeneity could not be assessed.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Our meta-analysis showed that using statins decreases the risk of developing CRC in patients with IBD. Both HR and OR analyses demonstrated a decreased risk of developing CRC in patients on statins. However, the HR analysis was statistically significant, while the OR analysis was not. The HR analysis was based on a higher number of patients (48,480 patients for HR versus 11,116 patients for OR). In addition, the HR analysis included studies that reported adjusted HRs and considered the time-to-development of CRC, as well as other confounding factors such as the duration of statin use and immunomodulator use, which could have impacted CRC development, thereby enhancing the reliability of those studies. Additionally, in subgroup analysis by IBD type, statin use was associated with a significantly reduced risk of CRC in patients with UC (HR = 0.64; 95% CI: 0.51 - 0.80). These findings are promising and could be helpful in chemoprevention against CRC in patients with IBD.

IBD and CRC

The relationship between IBD and malignancy risk is intricate. Several large population-based studies and systematic reviews have shown that the overall risk of malignancy in IBD patients is comparable to that of the general population [10, 17-19]. However, CRC remains a significant exception. Several studies have reported elevated rates of CRC in patients with IBD. In fact, IBD patients are 2 - 6 times more likely to develop CRC than the general population. This association highlights the increased risk of CRC development in individuals with IBD [20]. Two Scandinavian population-based cohort studies involving 96,447 patients with UC and 47,035 patients with CD showed that both UC and CD had a higher incidence of CRC compared to the reference group. The HR for UC was 1.66 (95% CI: 1.57 - 1.76), and 1.4 for CD (95% CI 1.27 - 1.53) [21, 22]. Another population-based study also showed that the risk for CRC was increased by 1.9-fold in IBD patients compared to the control population [11]. Cohort studies spanning from 1955 to 1989 revealed a relative risk of 4.1 (95% CI: 2.7 - 5.8) for CRC in patients with UC and a standardized incidence ratio (SIR) of 2.5 (95% CI: 1.3 - 4.3) for those with CD between 1965 and 1983 [23, 24]. Another cohort covering the years 1977 to 1989 reported a risk ratio of 1.8 (95% CI: 1.3 - 2.4) for CRC in UC patients [25]. A Canadian study found incidence rate ratios for CRC of 2.75 (95% CI: 1.91 - 3.97) for UC, 2.64 (95% CI: 1.69 - 4.12) for CD, and 2.71 (95% CI: 2.04 - 3.59) for IBD in general [26]. A meta-analysis by Eaden et al based on 116 studies reported that the incidence of CRC in UC patients was 4 to 10 times greater than that of sporadic CRC [27]. This increased risk of CRC emphasizes the importance of chemoprevention strategies in this high-risk population.

Risk factors for CRC in IBD patients

In patients with IBD, CRC develops within a chronically inflamed mucosal condition. These patients are at an increased risk of CRC due to chronic mucosal inflammation, as sustained mucosal injury results in repeated cycles of epithelial damage and regeneration, promoting dysplasia and neoplastic transformation [28]. Several studies proposed that chronic mucosal inflammation is a risk factor for developing microsatellite instability-high cancers in IBD patients, indicating that the biological behavior of IBD-associated cancers might differ from sporadic CRC [11, 29-32]. This risk is even higher in patients with pancolitis. Karlen et al showed that 94% of UC patients who developed cancer had total colitis, and 74% of those who developed rectal cancer also had pancolitis [23]. Additional studies have reported that the duration, extent, severity, and young age at diagnosis of UC are also key risk factors for increased risk of CRC in UC patients [33]. Other risk factors for CRC development were also described, including concomitant primary sclerosing cholangitis, pseudopolyps, and the duration of IBD [34-36].

Mechanisms of action of statins and cancer prevention

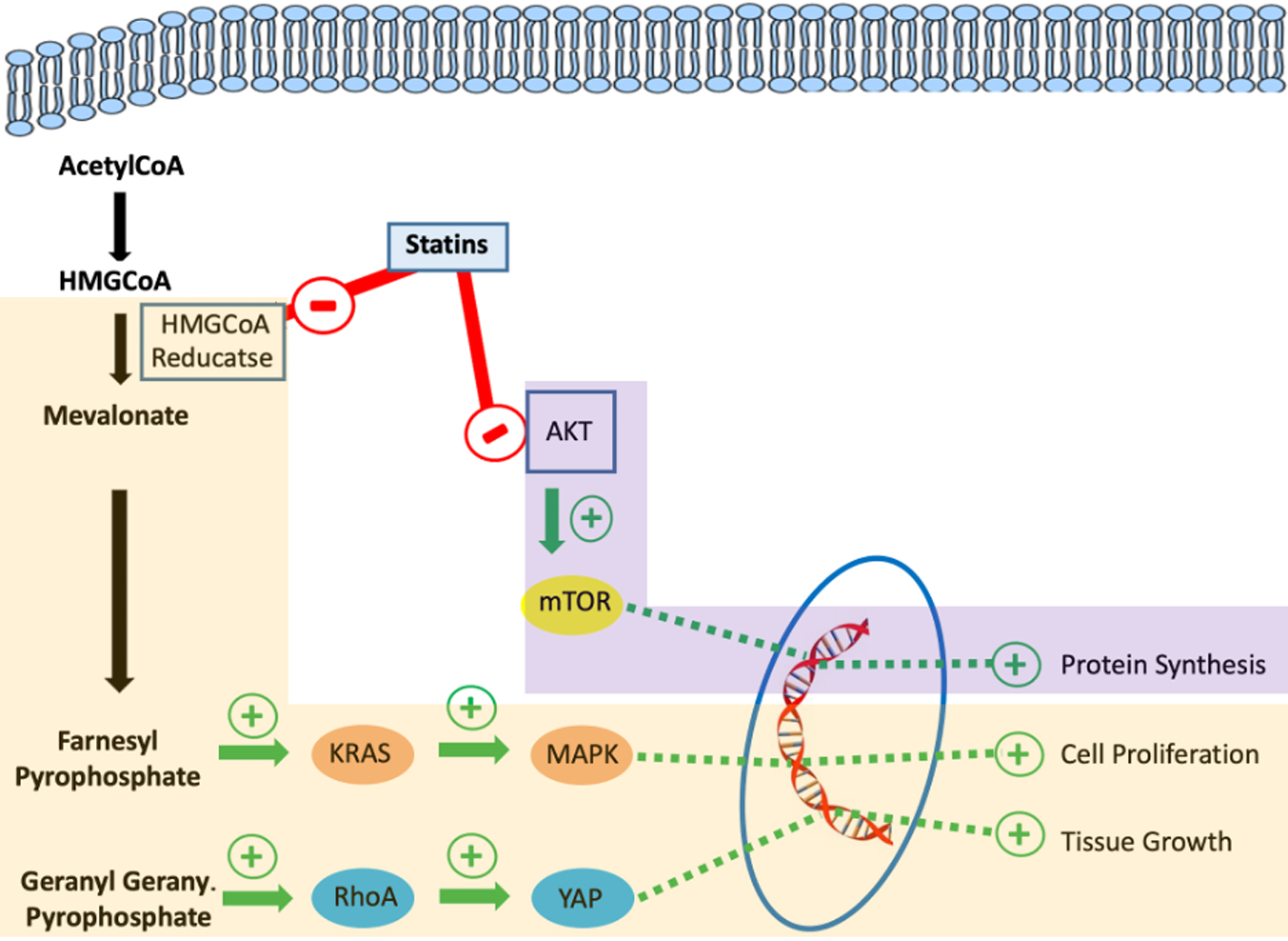

Statins are lipid-lowering medications used to treat hypercholesterolemia globally. Recently, they have shown anti-tumor effects by inhibiting cell proliferation and activating apoptosis. This may occur through 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibition and other non-HMG-CoA-related effects [5].

HMG-CoA reductase is the key rate-limiting enzyme in the mevalonate pathway, and by inhibiting HMG-CoA to mevalonate conversion, statins lower mevalonate and its downstream products, including Ras and Rho proteins, which are overexpressed in CRC and linked to tumor invasion [37]. These mevalonate pathway products are essential for cellular functions such as maintaining membrane integrity, regulating cell signaling, facilitating protein synthesis, and promoting cell cycle progression. Disrupting these processes in cancer cells could impact tumor initiation, growth, and metastasis [38].

Other mechanisms of action of statins, independent of HMG-CoA reductase, have also been described and may play a role in cancer prevention. These effects may include inhibiting cell adhesion and angiogenesis, providing antioxidant benefits, and reducing inflammation. The downregulation and inhibition of matrix metalloproteinases, key enzymes in the degradation of the extracellular matrix, decrease the risk of invasion and metastasis of cancerous cells [39, 40]. Statins also induce the inhibition of downstream signaling pathways in the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) system, ultimately affecting mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) expression, which is responsible for regulating cell growth [41]. Statin can also induce apoptosis through its increased expression of the p53 tumor suppressor protein, which reduces cellular proliferation and induces apoptosis [42]. These pro-apoptotic and anti-inflammatory effects of statins support the potential protective effect of statins against CRC. Suggested cellular mechanisms of action through which statins reduce the risk of cancers are depicted in Figure 8.

Click for large image | Figure 8. Suggested cellular mechanisms of action through which statins reduce the risk of cancer development. |

Statins and CRC in the general population

Despite the mechanistic rationale, studies evaluating the effect of statins on CRC risk in the general population have yielded mixed results [37]. Several cohort studies have shown a non-statistically significant benefit of statin use on the risk of developing CRC [43-46]. Other population-based studies described a significantly reduced relative risk of CRC [12, 47, 48]. Lee et al in two large prospective cohort studies showed that statins reduce the risk of rectal cancer but not colon cancer [49]. Multiple comprehensive meta-analyses showed that statin use was generally associated with a modest reduction in CRC risk. This effect was more pronounced and statistically significant in observational studies (cohort and case-control studies) compared to RCTs, where the reduction did not reach statistical significance [8, 9, 50, 51]. Similarly, a recent 2019 meta-analysis of 59 studies, including both RCTs and observational studies, found that statin use was associated with a reduced risk of CRC in observational studies (pooled relative risk = 0.92; 95% CI: 0.88 - 0.95); however, this association was not significant in RCTs (pooled relative risk = 0.92; 95% CI: 0.81 - 1.05) [6]. The discrepancy may be attributable to the relatively short follow-up periods in most RCTs (approximately 5 years), which may be insufficient to capture long-latency outcomes, such as cancer incidence, in an average-risk population.

Statins and CRC in IBD patients

Among IBD patients, studies investigating the potential benefit of statins on CRC are more limited. Up till today, a total of nine cohorts have analyzed the chemopreventive effect of statins, specifically in IBD patients, and two of them were abstracts with insufficient data to be included in the analysis. To our knowledge, this meta-analysis is the only one in the literature to include all available data and to be specifically conducted in an IBD population.

Poynter et al were the first to investigate the effect of statins on CRC in the IBD population. Statin use in the general population was associated with a significantly lower risk of CRC (OR: 0.53; 95% CI: 0.38 - 0.74). Upon examining the relationship between statin use and the risk of CRC among 55 patients with IBD, a protective effect of statins in this subgroup was also observed (OR: 0.06; 95% CI: 0.006 - 0.55) [12]. A few years later, a study by Samadder et al demonstrated that statin use significantly reduced CRC risk overall (OR: 0.49, 95% CI: 0.39 - 0.62), particularly IBD-associated CRC (OR: 0.10; 95% CI: 0.01 - 1.31), with simvastatin showing the most pronounced effect [11]. Later, Ananthakrishnan et al analyzed data from two tertiary referral centers and included 11,001 IBD patients. Among statin users, 30 patients (2%) developed CRC during a 9-year follow-up compared to 287 statin non-users (3%). Statin use showed a significant and independent inverse association with CRC (OR: 0.42; 95% CI: 0.28 - 0.62) [13].

Another cohort study by Shah et al, involving 642 IBD patients, showed that the statin exposed group had a lower risk of CRC development compared to the non-exposed group (1.8% vs. 2.9% respectively); however, this was not statistically significant (HR: 0.56; 95% CI: 0.06 - 4.92) [14].

Mak et al also evaluated CRC occurrence in 2,103 IBD patients (857 with CD and 1,246 with UC). Forty-eight patients (2.3%) developed cancer, and 222 patients (10.6%) received statins. Multivariable analysis showed reduced cancer risk in statin users; however, it was not statistically significant (HR: 0.48; 95% CI: 0.14 - 1.59) [15]. More recently, Oh et al, in a nationwide population-based study, evaluated the chemopreventive effects of statins, metformin, and aspirin on various malignancies, including sporadic CRC in patients with UC. Statins showed a dose-dependent chemopreventive effect for all malignancies in UC patients (HR: 0.764; 95% CI: 0.645 - 0.905; P = 0.002), whereas metformin and aspirin did not (P > 0.05). However, when analyzing the risk of CRC in UC patients using statins, there was no difference between statin users and non-users (35% in both groups) with an HR of 0.844 (95% CI: 0.535 - 1.332), which was not statistically significant [10]. Another recent IBD conducted by Sun et al included a cohort of 5,273 statin users and 5,273 non-statin users, which showed an incidence of CRC in 70 statin users compared to 90 non-statin users, with an HR of 0.76 (95% CI: 0.61 - 0.96). Statin users also had reduced risks of CRC-related mortality (HR: 0.56; 95% CI: 0.37 - 0.83) and all-cause mortality (HR: 0.63; 95% CI: 0.57 - 0.69) [16].

An abstract of a retrospective study involving 2,978 patients aimed to identify the risk factors associated with CRC in patients with CD and UC. Statins were associated with a lower risk of developing CRC in both UC and CD patients. However, the results were not statistically significant, with an OR of 0.854 (95% CI: 0.176 - 2.639) in CD patients and an OR of 0.645 (95% CI: 0.140 - 2.973) in UC patients. These findings were excluded from our analysis due to unavailable data on the number of patients using statins and the proportion of those who developed CRC, thereby preventing their inclusion in the analysis [52]. Another abstract of a 2020 meta-analysis examined the association between statin use and CRC risk in both non-IBD and IBD populations. Among non-IBD patients, statin use showed a significant reduction in CRC risk (OR: 0.80; 95% CI: 0.73 - 0.88), with no evidence of publication bias. For IBD patients, five observational studies (including one unpublished abstract) were analyzed, involving 15,342 IBD patients, to show that statin use was also associated with a significant CRC risk reduction (OR: 0.40; 95% CI: 0.19 - 0.86; P = 0.019), though publication bias was detected in these findings [53]. Another abstract of a 2020 meta-analysis also aimed to assess the role of statins in IBD patients for CRC prevention. Three retrospective studies were included, involving 11,703 patients with IBD. A pooled analysis revealed a significant 60% reduction in the odds of CRC associated with statin use (OR: 0.41; 95% CI: 0.28 - 0.60). There was no evidence of publication bias [54]. However, the findings of both meta-analyses are outdated, with small sample sizes of IBD patients and incomplete inclusion of available data up to the present day.

Limitations

Our meta-analysis has certain limitations. First, all included studies were retrospective observational in nature, which introduces potential for selection bias, confounding factors, and inconsistent documentation of medication use. Additionally, variability among the included studies, such as differences in study design, patient populations, interventions, and outcome measures, limits the generalizability and interpretability of pooled estimates. Funnel plots were used to explore the potential for publication bias; however, given the small number of studies included in each meta-analysis (n = 3 and n = 4), the interpretability of these plots is limited. Therefore, conclusions regarding publication bias should be drawn with caution. Lastly, the limited number of studies and the lack of access to individual patient data limit the ability to perform detailed subgroup analyses based on IBD type (UC vs. CD), statin type, or treatment duration, as well as to adjust for confounding variables. These limitations highlight the need for further investigation in future prospective studies.

Conclusion and future directions

Our meta-analysis suggests a potential protective association between statin use and the risk of CRC in patients with IBD. This association was statistically significant in the HR-based analysis using a larger dataset, but not in the OR-based analysis, likely due to the variability and heterogeneity among included studies.

While the findings are promising, they rely on observational data, making large-scale prospective studies and RCTs necessary to validate these results and determine the optimal timing for initiation, precise dosages, and duration to achieve clinical benefits. This validation is essential before safely incorporating statins into the therapeutic options for CRC chemoprevention in IBD patients.

| Supplementary Material | ▴Top |

Suppl 1. Librarian’s complete search strategy.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

The authors declare no grants or financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. No funding, support, or involvement from pharmaceutical companies or other commercial entities was received for the conduct of this study.

Informed Consent

Informed consent and IRB approval were not required for this study, as it is a meta-analysis based on previously published data.

Author Contributions

Joelle Sleiman and Brendan Plann-Curley conducted the literature search. Joelle Sleiman, Un Jung Lee, and Cristina Sison conducted the study design and statistical analysis. Joelle Sleiman, Malek Kreidieh, Peter Khouri, and Liliane Deeb drafted the manuscript and its critical revision.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

CD: Crohn’s disease; CI: confidence interval; CRC: colorectal cancer; HR: hazard ratio; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; OR: odds ratio; RCT: randomized controlled trial; SIR: standardized incidence ratio; UC: ulcerative colitis

| References | ▴Top |

- Zhang YZ, Li YY. Inflammatory bowel disease: pathogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(1):91-99.

doi pubmed - Bruner LP, White AM, Proksell S. Inflammatory bowel disease. Prim Care. 2023;50(3):411-427.

doi pubmed - Shah SC, Itzkowitz SH. Colorectal Cancer in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Mechanisms and Management. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(3):715-730.e713.

doi pubmed - Quaglio AEV, Grillo TG, De Oliveira ECS, Di Stasi LC, Sassaki LY. Gut microbiota, inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2022;28(30):4053-4060.

doi pubmed - Lochhead P, Chan AT. Statins and colorectal cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11(2):109-118.

doi pubmed - Jeong GH, Lee KH, Kim JY, Eisenhut M, Kronbichler A, van der Vliet HJ, Hong SH, et al. Effect of statin on cancer incidence: an umbrella systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med. 2019;8(6):819.

doi pubmed - Benjamin DJ, Haslam A, Prasad V. Cardiovascular/anti-inflammatory drugs repurposed for treating or preventing cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Cancer Med. 2024;13(5):e7049.

doi pubmed - Liu Y, Tang W, Wang J, Xie L, Li T, He Y, Deng Y, et al. Association between statin use and colorectal cancer risk: a meta-analysis of 42 studies. Cancer Causes Control. 2014;25(2):237-249.

doi pubmed - Lytras T, Nikolopoulos G, Bonovas S. Statins and the risk of colorectal cancer: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of 40 studies. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(7):1858-1870.

doi pubmed - Oh EH, Kim YJ, Kim M, Park SH, Kim TO, Park SH. Risk of malignancies and chemopreventive effect of statin, metformin, and aspirin in Korean patients with ulcerative colitis: a nationwide population-based study. Intest Res. 2025;23(2):129-143.

doi pubmed - Samadder NJ, Mukherjee B, Huang SC, Ahn J, Rennert HS, Greenson JK, Rennert G, et al. Risk of colorectal cancer in self-reported inflammatory bowel disease and modification of risk by statin and NSAID use. Cancer. 2011;117(8):1640-1648.

doi pubmed - Poynter JN, Gruber SB, Higgins PD, Almog R, Bonner JD, Rennert HS, Low M, et al. Statins and the risk of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(21):2184-2192.

doi pubmed - Ananthakrishnan AN, Cagan A, Cai T, Gainer VS, Shaw SY, Churchill S, Karlson EW, et al. Statin use is associated with reduced risk of colorectal cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(7):973-979.

doi pubmed - Shah SC, Glass J, Giustino G, Hove JRT, Castaneda D, Torres J, Kumar A, et al. Statin exposure is not associated with reduced prevalence of colorectal neoplasia in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gut Liver. 2019;13(1):54-61.

doi pubmed - Mak JWY, So J, Tang W, Yip TCF, Leung WK, Li M, Lo FH, et al. Cancer risk and chemoprevention in Chinese inflammatory bowel disease patients: a population-based cohort study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2020;55(3):279-286.

doi pubmed - Sun J, Halfvarson J, Bergman D, Ebrahimi F, Roelstraete B, Lochhead P, Song M, et al. Statin use and risk of colorectal cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. EClinicalMedicine. 2023;63:102182.

doi pubmed - Burisch J, Jess T, Martinato M, Lakatos PL, EpiCom E. The burden of inflammatory bowel disease in Europe. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7(4):322-337.

doi pubmed - Katsanos KH, Tatsioni A, Pedersen N, Shuhaibar M, Ramirez VH, Politi P, Rombrechts E, et al. Cancer in inflammatory bowel disease 15 years after diagnosis in a population-based European Collaborative follow-up study. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5(5):430-442.

doi pubmed - Greuter T, Vavricka S, Konig AO, Beaugerie L, Scharl M, on behalf of Swiss IBDnet, an official working group of the Swiss Society of Gastroenterology. Malignancies in inflammatory bowel disease. Digestion. 2020;101(Suppl 1):136-145.

doi pubmed - Keller DS, Windsor A, Cohen R, Chand M. Colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: review of the evidence. Tech Coloproctol. 2019;23(1):3-13.

doi pubmed - Olen O, Erichsen R, Sachs MC, Pedersen L, Halfvarson J, Askling J, Ekbom A, et al. Colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: a Scandinavian population-based cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10218):123-131.

doi pubmed - Olen O, Erichsen R, Sachs MC, Pedersen L, Halfvarson J, Askling J, Ekbom A, et al. Colorectal cancer in Crohn's disease: a Scandinavian population-based cohort study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(5):475-484.

doi pubmed - Karlen P, Lofberg R, Brostrom O, Leijonmarck CE, Hellers G, Persson PG. Increased risk of cancer in ulcerative colitis: a population-based cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(4):1047-1052.

doi pubmed - Ekbom A, Helmick C, Zack M, Adami HO. Increased risk of large-bowel cancer in Crohn's disease with colonic involvement. Lancet. 1990;336(8711):357-359.

doi pubmed - Mellemkjaer L, Olsen JH, Frisch M, Johansen C, Gridley G, McLaughlin JK. Cancer in patients with ulcerative colitis. Int J Cancer. 1995;60(3):330-333.

doi pubmed - Bernstein CN, Blanchard JF, Kliewer E, Wajda A. Cancer risk in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Cancer. 2001;91(4):854-862.

doi pubmed - Eaden JA, Abrams KR, Mayberry JF. The risk of colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis. Gut. 2001;48(4):526-535.

doi pubmed - Murata M. Inflammation and cancer. Environ Health Prev Med. 2018;23(1):50.

doi pubmed - Fleisher AS, Esteller M, Harpaz N, Leytin A, Rashid A, Xu Y, Liang J, et al. Microsatellite instability in inflammatory bowel disease-associated neoplastic lesions is associated with hypermethylation and diminished expression of the DNA mismatch repair gene, hMLH1. Cancer Res. 2000;60(17):4864-4868.

pubmed - Cawkwell L, Sutherland F, Murgatroyd H, Jarvis P, Gray S, Cross D, Shepherd N, et al. Defective hMSH2/hMLH1 protein expression is seen infrequently in ulcerative colitis associated colorectal cancers. Gut. 2000;46(3):367-369.

doi pubmed - Svrcek M, El-Bchiri J, Chalastanis A, Capel E, Dumont S, Buhard O, Oliveira C, et al. Specific clinical and biological features characterize inflammatory bowel disease associated colorectal cancers showing microsatellite instability. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(27):4231-4238.

doi pubmed - Schulmann K, Mori Y, Croog V, Yin J, Olaru A, Sterian A, Sato F, et al. Molecular phenotype of inflammatory bowel disease-associated neoplasms with microsatellite instability. Gastroenterology. 2005;129(1):74-85.

doi pubmed - Watanabe T, Konishi T, Kishimoto J, Kotake K, Muto T, Sugihara K, Japanese Society for Cancer of the C, et al. Ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer shows a poorer survival than sporadic colorectal cancer: a nationwide Japanese study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17(3):802-808.

doi pubmed - Baars JE, Looman CW, Steyerberg EW, Beukers R, Tan AC, Weusten BL, Kuipers EJ, et al. The risk of inflammatory bowel disease-related colorectal carcinoma is limited: results from a nationwide nested case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(2):319-328.

doi pubmed - Wang R, Leong RW. Primary sclerosing cholangitis as an independent risk factor for colorectal cancer in the context of inflammatory bowel disease: a review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(27):8783-8789.

doi pubmed - Trivedi PJ, Crothers H, Mytton J, Bosch S, Iqbal T, Ferguson J, Hirschfield GM. Effects of primary sclerosing cholangitis on risks of cancer and death in people with inflammatory bowel disease, based on sex, race, and age. Gastroenterology. 2020;159(3):915-928.

doi pubmed - Demierre MF, Higgins PD, Gruber SB, Hawk E, Lippman SM. Statins and cancer prevention. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5(12):930-942.

doi pubmed - Wong WW, Dimitroulakos J, Minden MD, Penn LZ. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors and the malignant cell: the statin family of drugs as triggers of tumor-specific apoptosis. Leukemia. 2002;16(4):508-519.

doi pubmed - Zhu Z, Cao Y, Liu L, Zhao Z, Yin H, Wang H. Atorvastatin regulates the migration and invasion of prostate cancer through the epithelial-mesenchymal transformation and matrix metalloproteinase pathways. Investig Clin Urol. 2022;63(3):350-358.

doi pubmed - Mannello F, Tonti GA. Statins and breast cancer: may matrix metalloproteinase be the missing link. Cancer Invest. 2009;27(4):466-470.

doi pubmed - Fliedner SM, Engel T, Lendvai NK, Shankavaram U, Nolting S, Wesley R, Elkahloun AG, et al. Anti-cancer potential of MAPK pathway inhibition in paragangliomas-effect of different statins on mouse pheochromocytoma cells. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e97712.

doi pubmed - Parrales A, Thoenen E, Iwakuma T. The interplay between mutant p53 and the mevalonate pathway. Cell Death Differ. 2018;25(3):460-470.

doi pubmed - Singh H, Mahmud SM, Turner D, Xue L, Demers AA, Bernstein CN. Long-term use of statins and risk of colorectal cancer: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(12):3015-3023.

doi pubmed - Friis S, Poulsen AH, Johnsen SP, McLaughlin JK, Fryzek JP, Dalton SO, Sorensen HT, et al. Cancer risk among statin users: a population-based cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2005;114(4):643-647.

doi pubmed - Blais L, Desgagne A, LeLorier J. 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors and the risk of cancer: a nested case-control study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(15):2363-2368.

doi pubmed - Graaf MR, Beiderbeck AB, Egberts AC, Richel DJ, Guchelaar HJ. The risk of cancer in users of statins. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(12):2388-2394.

doi pubmed - Hoffmeister M, Chang-Claude J, Brenner H. Individual and joint use of statins and low-dose aspirin and risk of colorectal cancer: a population-based case-control study. Int J Cancer. 2007;121(6):1325-1330.

doi pubmed - Hachem C, Morgan R, Johnson M, Kuebeler M, El-Serag H. Statins and the risk of colorectal carcinoma: a nested case-control study in veterans with diabetes. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(5):1241-1248.

doi pubmed - Lee JE, Baba Y, Ng K, Giovannucci E, Fuchs CS, Ogino S, Chan AT. Statin use and colorectal cancer risk according to molecular subtypes in two large prospective cohort studies. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2011;4(11):1808-1815.

doi pubmed - Bardou M, Barkun A, Martel M. Effect of statin therapy on colorectal cancer. Gut. 2010;59(11):1572-1585.

doi pubmed - Bonovas S, Filioussi K, Flordellis CS, Sitaras NM. Statins and the risk of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of 18 studies involving more than 1.5 million patients. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(23):3462-3468.

doi pubmed - Ghimire S, Gondal A, Talluri S, Budhathoki R, Sharma S, Khan HM, Georgetson MJ. S0774 risk factors for colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: observations from a single center. Am J Gastroenterol 2020;115:S395-S395.

doi - Singh KN, Yakubov S, Nadeem AJ. S0265 statin use reduces the risk of colorectal cancer: an updated meta-analysis and systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol 2020;115:S129-S129.

doi - Radadiya D, Devani K, Dziadkowiec KN, Charilaou P, Reddy C. S0739 chemoprevention of colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease with statin: a meta-analysis of available literature. Am J Gastroenterol 2020;115:S371-S372.

doi

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Gastroenterology Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.