| Gastroenterology Research, ISSN 1918-2805 print, 1918-2813 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, Gastroenterol Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://gr.elmerpub.com |

Original Article

Volume 18, Number 3, June 2025, pages 129-138

Impact of Hospital Teaching Status on Outcomes of Acute Cholangitis: A Propensity-Matched Analysis of Hospitalizations in the United States

Karan J. Yagnika, l, Raj Patelb, Sneh Sonaiyac, Charmy Parikhd, Pranav Patele, Yash Shahf, Umar Hayatg, Dushyant Singh Dahiyah, Dhruvil Radadiyai, Hareesha Rishab Bharadwajj, Doantrang Dua, Ben Terranyk, Dharmesh Kaswalak, Bradley Confere, Harshit S. Kharae

aDepartment of Medicine, Rutgers School of Medicine/Monmouth Medical Center, Long Branch, NJ 07740, USA

bDepartment of Medicine, St. Mary Medical Center, Langhorne, PA 19047, USA

cDepartment of Medicine, Kirk Kerkorian School of Medicine at UNLV, Las Vegas, NV 89102, USA

dDepartment of Medicine, Mercy Catholic Medical Center, Darby, PA 19023, USA

eDepartment of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Geisinger Health, Danville, PA 17822, USA

fDepartment of Medicine, Trinity Health Oakland/Wayne State University, Pontiac, MI 48341, USA

gDepartment of Medicine, Geisinger Health, Wikes Barre, PA 18765, USA

hDepartment of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Motility, University of Kansas School of Medicine, Kansas City, KS 66103, USA

iDepartment of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Cedar Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA 90048, USA

jFaculty of Biology Medicine and Health, The University of Manchester, UK

kDepartment of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Monmouth Medical Center, NJ 07740, USA

lCorresponding Author: Karan J. Yagnik, Department of Internal Medicine, Robert Wood Johnson Barnabas Health/Monmouth Medical Center, Long Branch, NJ 07740, USA

Manuscript submitted March 28, 2025, accepted May 15, 2025, published online June 4, 2025

Short title: Acute Cholangitis: Teaching vs. Non-Teaching

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/gr2038

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Acute cholangitis (AC) is a serious condition caused by partial or complete obstruction of the common bile duct (CBD), leading to biliary tract infection. We aimed to evaluate whether teaching hospitals with trainees and non-teaching hospitals impact the outcome of AC in the United States.

Methods: This study utilized the National Inpatient Sample database to analyze adult hospitalizations (> 18 years old) with a primary diagnosis of AC in the USA from 2016 to 2020. A multivariate logistic regression along with Chi-square and t-tests was performed using SAS 9.4 software to analyze inpatient AC-associated mortality, inflation-adjusted total hospitalization costs (THC), and length of stay (LOS) in US teaching and non-teaching hospitals during the study period.

Results: This study included a total of 30,300 patients, out of whom 23,535 (about 78%) were managed in teaching hospitals and 6,765 (about 22%) were managed in non-teaching hospitals. Primary outcomes showed a significant increase in mortality for patients managed in teaching hospitals (2.77% vs. 2.08%, P = 0.01) in comparison to non-teaching hospitals, hospital LOS was slightly higher in teaching hospitals (5 days (interquartile range (IQR): 3 - 6) vs. 4 days (IQR: 3 - 8)) and so did hospital cost ($15,259 vs. $14,506) in comparison to non-teaching hospitals. Secondary outcomes showed that patients in teaching hospitals had higher incidence of septic shock (16.06% vs. 12.53%, P < 0.0001), intensive care unit (ICU) admissions (6.61% vs. 5.07%, P = 0.0002), and intubation (5.30% vs. 3.46%, P < 0.0001) in comparison to non-teaching hospitals.

Conclusion: Our study found higher mortality rates for AC patients in teaching hospitals compared to non-teaching hospitals. Teaching hospitals also had higher rates of septic shock, ICU admission, and intubation, with no difference in endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) use. These differences could be due to several factors, such as greater resident and fellow autonomy in teaching hospitals and a potentially more proactive approach by physicians in non-teaching hospitals. Additionally, teaching hospitals often manage more complex, higher-acuity cases, which could contribute to worse outcomes.

Keywords: Acute cholangitis; Teaching hospitals; Outcomes; Hospital mortality; Hospital charges; Hospital length of stay; National Inpatient Sample database

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Acute cholangitis (AC) also referred as ascending cholangitis is a potentially life-threatening condition caused by partial or complete obstruction of the common bile duct (CBD), leading to infection of the biliary tract and characterized by abdominal pain, fever, and jaundice. Obstruction primarily occurs due to gallstones. In certain cases, benign biliary strictures and malignancy may be culprit. Due to its severity and the risk of rapid clinical deterioration, AC requires immediate medical attention and prompt treatment. Current mortality rate in AC varies between 2% and 10% [1-3]. Delays in management can result in septic shock, which is the most common cause of death in AC [4, 5]. Treatment typically involves supportive care, administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics, and timely biliary drainage, which should be performed urgently (within 24 h) or early (within 24 - 48 h) via endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) [6, 7].

In the United States, hospitals are typically categorized into teaching and non-teaching institutions, based on their involvement in medical education. Teaching hospitals serve as training grounds for medical students, residents, subspecialty fellows, and other healthcare trainees, providing them with hands-on experience under the guidance of academic physicians. The effect of a hospital’s teaching status on patient safety and care outcomes remains uncertain [8]. While some studies have suggested that teaching hospitals offer higher quality care and better patient outcomes compared to non-teaching hospitals, more recent research indicates that teaching status may have little to no significant impact on overall clinical outcomes [8-13]. However, outcomes may vary depending on specific disease and patient characteristics [9]. Additionally, certain studies have noted that teaching hospitals might experience higher rates of iatrogenic injuries, although the reasons for this discrepancy remain unclear [14].

Previously, multiple studies have been done to compare the outcomes of upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding in teaching and non-teaching hospitals [15-17]. It has been studied about the impact of timing of ERCP, racial, and ethnic disparities on the outcomes of AC in the USA [6, 18, 19]. Lack of study to compare outcomes in teaching and non-teaching hospitals for AC has prompted us to do first ever study to evaluate the impact of the teaching status of healthcare institutions on the disease-specific outcomes of AC in the United States.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

Study design, database description, and data availability

This retrospective, cross-sectional study utilized the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) to analyze hospitalizations in the United States from 2016 to 2020. The NIS, a component of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) maintained by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), is one of the largest publicly available, all-payer databases. Derived from billing data submitted by hospitals to statewide data organizations, the NIS provides a weighted dataset representing over 35 million hospital admissions annually, covering 97% of the US population. It approximates a 20% stratified sample of discharges from US community hospitals, allowing for the generation of national estimates. The dataset includes key information such as patient demographics, hospital characteristics (e.g., size and location), primary discharge diagnosis, and procedures performed during hospital stays. Since October 2015, the NIS has been coded using the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification/Procedure Coding System (ICD-10-CM/PCS). As a publicly accessible, de-identified database, it does not require Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval for use.

Study population and variables

This study included all adults (aged > 18 years) admitted to US hospitals with a primary diagnosis of AC from 2016 to 2020, identified using ICD-10 codes from the NIS database. Patients under 18 years of age were excluded. The study population was divided into two subgroups based on the NIS classification of hospital type: 1) teaching hospitals: hospitals with one or more Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)-approved residency programs, membership in the Council of Teaching Hospitals (COTH), or a ratio of full-time equivalent interns and residents to beds of 0.25 or higher; and 2) non-teaching hospitals: hospitals not meeting the criteria for teaching hospitals.

Outcomes were categorized into two groups: 1) primary outcomes: in-hospital mortality, hospital length of stay (LOS), and total hospitalization costs (THC), adjusted for inflation to 2020 values using the AHRQ Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) 2020 Index for inpatient hospital care as a reference; and 2) secondary outcomes: incidence of septic shock, ICU admission, requirement for intubation, central venous catheter (CVC) placement, ERCP utilization, and associated conditions such as choledocholithiasis, gallstone pancreatitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), and biliary stricture.

All primary and secondary outcomes were compared between teaching and non-teaching hospitals, with trends analyzed over the 2016 - 2020 period.

In addition, hospitalization trend in relation to patient demographics, insurance status, median household income, hospital location (four main regions based upon the United States Census Bureau), presence of other comorbidities (congestive heart failure (CHF), hypertension (HTN), diabetes mellitus, alcohol abuse, and liver cirrhosis) was analyzed.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute). Weighted values provided by HCUP were applied to generate nationally representative estimates. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the study population, and Chi-square and t-tests were conducted to assess differences in categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Descriptive statistics were presented as the mean with standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and as counts with percentages for categorical variables. Associations between demographic variables, comorbidity profiles, hospital characteristics, and both primary and secondary outcomes were assessed using the Mantel-Haenszel design-adjusted Chi-square test, which accounts for the stratified survey design. Differences in median age, median LOS, and median THC were analyzed using a weighted regression model. Trends over time were analyzed using Chi-square tests for trend or t-tests, as appropriate. Multivariable logistic regression was employed to calculate odds for other outcomes.

Propensity score matching (1:1) was performed to adjust for baseline differences, including patient demographics, insurance types, median household income quartiles, comorbidities, and hospital characteristics. Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported. A P-value of ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

Ethical considerations

As the NIS database is de-identified and does not contain patient or hospital-specific information, our study is exempt from Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval based on our institution’s guidelines for HCUP-NIS database research. This study was carried out in compliance with ethical principles governing human research and the Helsinki Declaration.

| Results | ▴Top |

Patient characteristics and hospital characteristics

A total of 30,300 patients diagnosed with AC and treated in the United States from 2016 to 2020 were included in this study. Of these, 23,535 (about 78%) were treated in teaching hospitals, while 6,765 (about 22%) received care in non-teaching hospitals.

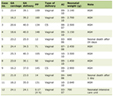

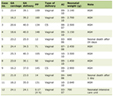

Over the 5-year period, trends for teaching hospitals showed that approximately half of the patients were female and over 65% were Caucasian. The mean age in this group was 70 ± 36 years. Similarly, trends for non-teaching hospitals indicated that nearly half of the patients were female and more than 70% were Caucasian. The mean age in this group was 71 ± 35 years. Baseline patient characteristics for non-teaching and teaching hospitals during 2016 - 2020 are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Click to view | Table 1. Baseline Patient Characteristics of Acute Cholangitis in Non-Teaching Hospitals |

Click to view | Table 2. Baseline Patient Characteristics of Acute Cholangitis in Teaching Hospitals |

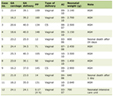

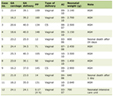

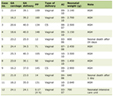

Comparison showed more female patients in non-teaching hospitals (51.19% vs. 48.89%, P = 0.008), more Caucasian in non-teaching patients (77.86% vs. 72.71%), but more African American (4.61% vs. 3.61%) as well as other population in teaching hospitals (22.67% vs. 18.52%) (P < 0.0001). Patients admitted in non-teaching hospitals had more comorbidities like CHF and HTN, while teaching hospitals had more patients with alcohol use disorder and liver cirrhosis. A comparison of baseline patient characteristics between the two groups is summarized Table 3.

Click to view | Table 3. Baseline Patients Characteristics Comparisona for Non-Teaching vs. Teaching Hospitals in Patients With Acute Cholangitis |

Primary outcomes

Inpatient mortality

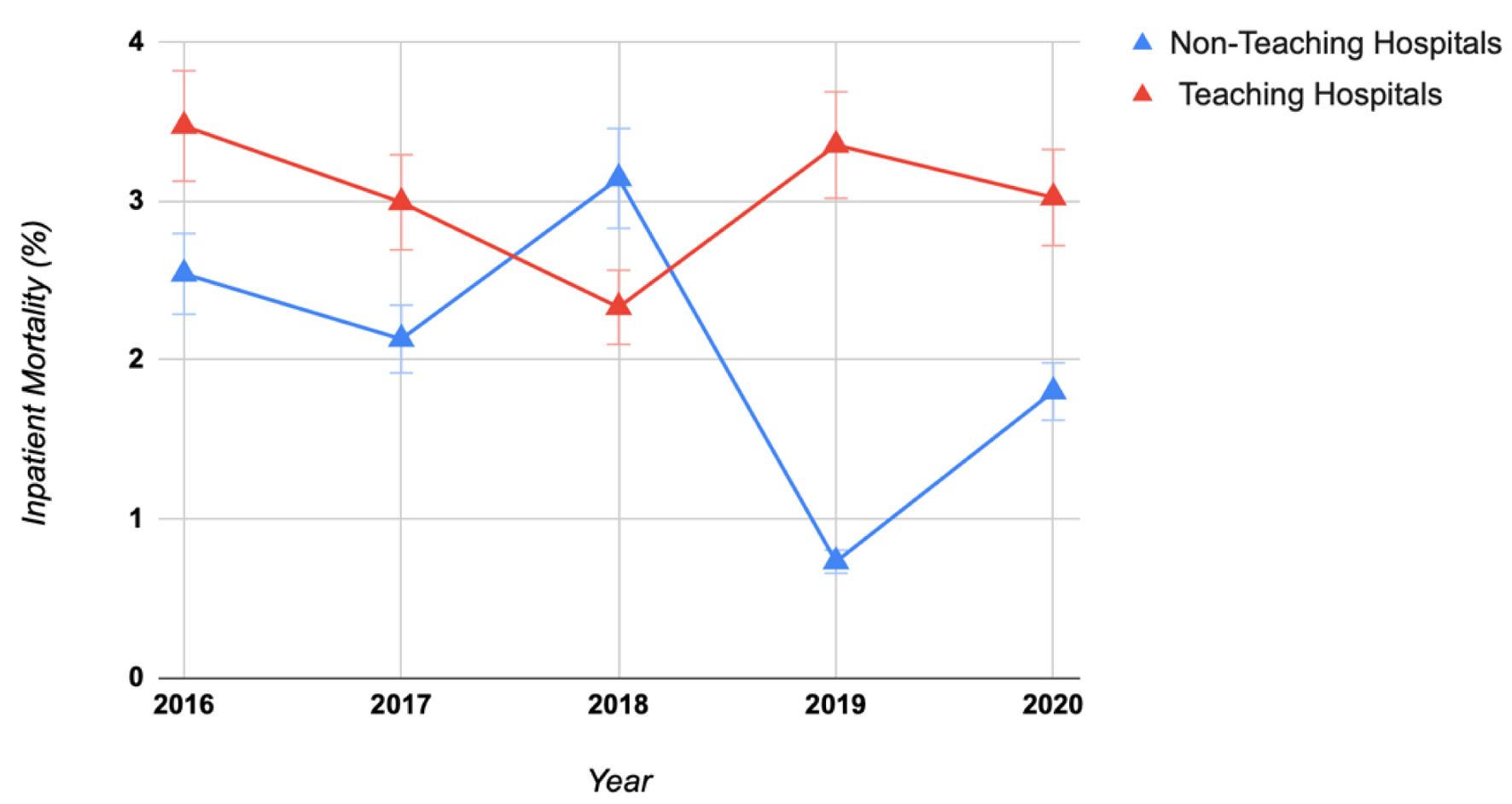

Inpatient mortality remained relatively stable over the 5-year period for teaching hospitals, with some variability between years. In contrast, non-teaching hospitals experienced a decline in inpatient mortality during the same timeframe. A comparison revealed significantly higher mortality rates in teaching hospitals compared to non-teaching hospitals (2.77% vs. 2.08%, P = 0.01) during the study period (Fig. 1).

Click for large image | Figure 1. Comparison of inpatient mortality in acute cholangitis in teaching vs. non-teaching hospitals. National Inpatient Sample database (2016 - 2020). |

Hospital LOS

Hospital LOS for teaching hospitals remained consistent at 6 - 7 days, while LOS decreased over time for non-teaching hospitals. On average, LOS was slightly longer in teaching hospitals compared to non-teaching hospitals (6.38 ± 16.12 vs. 5.54 ± 10.87 days).

THC

THC increased in teaching hospitals, rising from $20,287 to $23,390 between 2016 and 2020. In contrast, THC decreased in non-teaching hospitals, declining from $19,993 to $18,763 during the same period. Overall, THC was higher in teaching hospitals compared to non-teaching hospitals ($21,251 vs. $18,547).

Secondary outcomes

Teaching hospitals had a higher incidence of septic shock (16.06% vs. 12.53%, P < 0.0001), ICU admissions (6.61% vs. 5.07%, P = 0.0002), and intubation (5.30% vs. 3.46%, P < 0.0001) in comparison to non-teaching hospitals. However, there was no significant difference between two groups for the CVC placement (2.23% vs. 2.31%, P = 0.768) and ERCP performed (2.61% vs. 2.46%, P = 0.5771).

Moreover, non-teaching hospitals had significantly higher numbers of gallstone than teaching hospitals (16.22% vs. 14.45%, P = 0.0051). Teaching hospitals had higher rates of patients with PSC (0.08% vs. 0%, P = 0.0253). There was no difference between patients with biliary stricture.

Primary and secondary outcomes are reported in Figure 2 and Tables 4-6.

Click for large image | Figure 2. Primary and secondary outcomes of acute cholangitis: comparative analysis between teaching and non-teaching hospitals. National Inpatient Sample database (2016 - 2020). CVC: central venous catheter; ERCP: endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; Gall Pan: gallstone pancreatitis; ICU: intensive care unit; PSC: primary sclerosing cholangitis. |

Click to view | Table 4. Primary and Secondary Outcomes Variables for Patients With Acute Cholangitis in Non-Teaching vs. Teaching Hospitalsa |

Click to view | Table 5. Primary and Secondary Outcome Trends in Acute Cholangitis in Non-Teaching Hospitals |

Click to view | Table 6. Primary and Secondary Outcome Trends in Acute Cholangitis in Teaching Hospitals |

Furthermore, we did subgroup analysis for only patients who underwent ERCP in both groups. Results showed that incidences of inpatients mortality (3.49% vs. 0%, P = 0.0260) and septic shock (15.12% vs. 6.06%, P = 0.0238) were higher in teaching hospitals; however, there were no significant difference for ICU admissions, CVC placement, and intubations (Table 7).

Click to view | Table 7. Primary and Secondary Outcomes Variables for Patients Who Underwent ERCP in Non-Teaching vs. Teaching Hospitalsa |

Additionally, we calculated the complication rates of ERCP procedure in both groups. We found that patients who underwent ERCP in teaching hospitals had higher rates of post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP) (4.65% vs. 0%, P = 0.0136) and cholecystitis (24.42% vs. 18.18%, P = 0.0065) than with non-teaching group; however, there was no difference for ERCP-associated bleeding and bowel perforation between two groups (Table 8).

Click to view | Table 8. Comparison of ERCP Complicationsa for Non-Teaching vs. Teaching Hospitals in Patients With Acute Cholangitis |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

This is the first study to see hospital teaching status effect on outcomes in AC. Main highlights of this study are teaching hospitals have significantly higher rates of inpatient mortality, septic shock, ICU admission, and intubation than non-teaching hospitals, although the differences are relatively small. Consequently, LOS and THC are also higher in teaching hospitals than in non-teaching hospitals. Higher mortality and complications such as septic shock could be attributed to more complex cases treated in the teaching hospitals [20]. Many of these teaching hospitals are affiliated with universities and often serve as tertiary referral centers. As publicly funded facilities rely heavily on government, Medicare and Medicaid subsidies for graduate medical education and patient quality care. These hospitals frequently treat underserved, high-risk populations and manage high-acuity cases [21-24]. Our study also found that teaching hospitals have a higher portion of Medicaid and self-payers compared to non-teaching hospitals. Many high-risk cases that cannot be managed at non-teaching hospitals, especially those located in underserved areas, are often referred to these tertiary centers, either from emergency departments or after unsuccessful attempts at procedures like ERCP drainage, or when more complex interventions are required.

Higher rates of complications such as septic shock, ICU requirement, and intubation in teaching hospitals could be linked to the presence of inexperienced trainees and the attenuated role of senior physicians in these settings [25]. Frequent rotations of interns, residents, and fellows across different services may result in delay in familiarizing with protocols, delayed order entries or inexperience leading to the premature initiation of procedures like intubation, particularly during night shifts. Additionally, resident work hour limitations and shift changes may impact patient care [12, 22]. Although some studies suggest that duty hour restrictions are associated with a reduction in overall mortality [12].

Furthermore, teaching hospitals have more LOS and THC than non-teaching hospitals, partially due to factors mentioned above, and several studies have consistently shown that costs are higher at teaching hospitals [20, 26-29]. This is likely due to their capacity to provide specialized care, perform advanced procedures, utilize cutting-edge diagnostic tools, lead in medical education and research, and care for underserved populations [13, 30]. Additionally, trainees often order extra tests, procedures, or consultations for educational purposes, which may not always be necessary for every patient [25]. These factors can contribute to both higher THC and extended LOS in teaching hospitals. Similar findings have been reported for outcomes related to variceal and non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeds [15, 16]. Sharbatji et al found no significant difference in outcomes for teaching and non-teaching hospitals, although LOS, THC, and endoscopy rates were notably higher for the teaching hospitals [17]. On the other hand, for hip fracture admissions, outcomes were better at teaching hospitals [27]. Additionally, a study by Chaudhry et al showed worse outcomes including mortality, shock, sepsis, and ICU admission in teaching hospitals [31]. These disparities were thought to be due to higher-acuity of cases as well as transfer of complex cases to teaching hospitals, which also serve as tertiary centers. However, non-GI studies showed either better outcomes in teaching hospitals [32] or no significant difference in two hospital status [9, 11]. This further raises a question regarding outcomes disparities between two settings for the GI emergencies. It is possible that many non-teaching hospitals do not have advance GI specialists, hence, all these high-acuity cases were being transferred to the referral centers, many of which also act as teaching hospitals. However, due to limitation of NIS database study, we cannot categorized those cases.

Our study has found an overall decrease in inpatient mortality from 2016 to 2020, largely due to advances in therapeutic endoscopy like balloon enteroscopy-guided biliary drainage or endoscopic ultrasound guided-biliary drainage. These innovations have improved the management of AC caused by choledocholithiasis, reducing the need for invasive procedures. As a result, the overall incidence of septic shock, ICU admission, and requirement of intubation and pressors has decreased especially in non-teaching hospitals. However, in teaching hospitals, septic shock and pressor requirements have increased, possibly due to higher-acuity cases. The reason for this disparity remains unclear.

Strength and limitations

Strength of our study is providing first ever information on outcomes of the AC based upon hospital teaching status. It has also provided an overall trend and outcomes of AC during the period of 2016 - 2020, using an NIS database. The primary strength of the NIS database is its large sample size, representing a significant portion of US hospital discharges. Apart from these, data variety, standardization of data, accessibility, and information regarding cost and charges are available. Outcomes are reported using multivariable logistic regression to calculate odds. Propensity score matching (1:1) was performed to adjust for baseline differences, including demographics, comorbidities, and hospital characteristics. While this study provides insight about trends and outcomes of AC in US hospitals over 5 years, it is not without limitations.

The NIS database records hospitalizations rather than individual patient data, which may lead to either an underestimation of prevalence by missing cases of AC in non-hospitalized patients or an overestimation by including multiple hospitalizations for the same patient. Additionally, as a retrospective study, this analysis is subject to the inherent limitations and biases associated with such studies. Since NIS data are based on hospitalizations diagnosed with AC rather than unique patients, important clinical details, such as the underlying cause, bacterial pathogens, timing of antibiotic administration, disease severity scores and clinical granularity, and availability of ERCP and ICU, are not available, limiting our ability to analyze prognostic factors influencing mortality. Lastly, as an administrative database reliant on coding, the potential for coding errors cannot be ruled out.

Conclusion

Our study found higher mortality rates for AC patients in teaching hospitals compared to non-teaching hospitals. Teaching hospitals also had higher rates of septic shock, ICU admission, and intubation, although ERCP use was similar across both the hospital types. These differences could be due to several factors, such as greater resident and fellow autonomy in teaching hospitals and a potentially more proactive approach by physicians in non-teaching hospitals. Additionally, teaching hospitals often manage more complex, higher-acuity cases, which could contribute to worse outcomes. While we used propensity matching to control for these confounders, complete adjustment might not have been possible. Hence, further research with randomized controlled prospective design is needed to understand reasons behind these disparities in outcomes of AC based upon hospital teaching status.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

Authors have no financial interests to disclose.

Conflict of Interest

Authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Informed Consent

This is an NIS database-based study. NIS does not have any patient identifying data so no informed consent is required.

Author Contributions

Karan J. Yagnik: conceptualization, data curation, writing original draft, project administration, and visualization. Raj Patel: methodology, software, formal analysis, resources, and data curation. Sneh Sonaiya: writing original draft and project administration. Charmy Parikh: writing original draft. Pranav Patel: review and editing, and validation. Yash Shah: review and editing. Umar Hayat: writing original draft. Dushyant Singh Dahiya: review and editing. Dhruvil Radadiya: review and editing. Hareesha Rishab Bharadwaj: review and editing, and supervision. Doantrang Du: review and editing, and validation. Ben Terrany: review and editing. Dharmesh Kaswala: review and editing, project administration, and supervision. Bradely Confer: review and editing, project administration, and supervision. Harshit S. Khara: review and editing, project administration, supervision, and validation.

Data Availability

We utilized the NIS database from 2016 to 2020 for our analysis. The NIS database is available at: https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp.

Abbreviations

AC: acute cholangitis; ACGME: Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education; AHRQ: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; CBD: common bile duct; CHF: congestive heart failure; COTH: Council of Teaching Hospitals; CVC: central venous catheter; ERCP: endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; HCUP: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project; HTN: hypertension; ICD-10-CM/PCS: International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification/Procedure Coding System; ICU: intensive care unit; IRB: Institutional Review Board; LOS: length of stay; MEPS: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey; NIS: National Inpatient Sample; OR: odds ratio; PCS: primary sclerosing cholangitis; SD: standard deviation; THC: total hospitalization costs; USA: United States of America

| References | ▴Top |

- Navaneethan U, Jayanthi V, Mohan P. Pathogenesis of cholangitis in obstructive jaundice-revisited. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2011;57(1):97-104.

pubmed - Yildiz BD, Ozden S, Saylam B, Martli F, Tez M. Simplified scoring system for prediction of mortality in acute suppurative cholangitis. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2018;34(7):415-419.

doi pubmed - Aboelsoud M, Siddique O, Morales A, Seol Y, Al-Qadi M. Early biliary drainage is associated with favourable outcomes in critically-ill patients with acute cholangitis. Prz Gastroenterol. 2018;13(1):16-21.

doi pubmed - Kimura Y, Takada T, Kawarada Y, Nimura Y, Hirata K, Sekimoto M, Yoshida M, et al. Definitions, pathophysiology, and epidemiology of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis: Tokyo Guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2007;14(1):15-26.

doi pubmed - Touzani S, El Bouazzaoui A, Bouyarmane F, Faraj K, Houari N, Boukatta B, Kanjaa N. Factors associated with mortality in severe acute cholangitis in a Moroccan intensive care unit: a retrospective analysis of 140 cases. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2021;2021:4583493.

doi pubmed - Parikh MP, Wadhwa V, Thota PN, Lopez R, Sanaka MR. Outcomes associated with timing of ERCP in acute cholangitis secondary to choledocholithiasis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2018;52(10):e97-e102.

doi pubmed - Buxbaum JL, Buitrago C, Lee A, Elmunzer BJ, Riaz A, Ceppa EP, Al-Haddad M, et al. ASGE guideline on the management of cholangitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;94(2):207-221.e214.

doi pubmed - International Working Party to Promote and Revitalise Academic Medicine. Academic medicine: the evidence base. BMJ. 2004;329(7469):789-792.

doi pubmed - Papanikolaou PN, Christidi GD, Ioannidis JP. Patient outcomes with teaching versus nonteaching healthcare: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2006;3(9):e341.

doi pubmed - Clark J, Tugwell P. Does academic medicine matter? PLoS Med. 2006;3(9):e340.

doi pubmed - Au AG, Padwal RS, Majumdar SR, McAlister FA. Patient outcomes in teaching versus nonteaching general internal medicine services: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):517-523.

doi pubmed - Shetty KD, Bhattacharya J. Changes in hospital mortality associated with residency work-hour regulations. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(2):73-80.

doi pubmed - Shelton J, Kummerow K, Phillips S, Arbogast PG, Griffin M, Holzman MD, Nealon W, et al. Patient safety in the era of the 80-hour workweek. J Surg Educ. 2014;71(4):551-559.

doi pubmed - John J, Seifi A. Incidence of iatrogenic pneumothorax in the United States in teaching vs. non-teaching hospitals from 2000 to 2012. J Crit Care. 2016;34:66-68.

doi pubmed - Patel P, Rotundo L, Orosz E, Afridi F, Pyrsopoulos N. Hospital teaching status on the outcomes of patients with esophageal variceal bleeding in the United States. World J Hepatol. 2020;12(6):288-297.

doi pubmed - Asotibe JC, Shaka H, Akuna E, Shekar N, Shah H, Ramirez M, Sherazi SAA, et al. Outcomes of non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleed stratified by hospital teaching status: insights from the national inpatient sample. Gastroenterology Res. 2021;14(5):268-274.

doi pubmed - Sharbatji M, Anand Sachin P, Abhishek R, Ali S, Ur Rahman A. Outcomes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding at united states teaching and non-teaching hospitals: a national inpatient sample analysis. Cureus. 2024;16(6):e61793.

doi pubmed - Wang M, Wadhwani SI, Cullaro G, Lai JC, Rubin JB. Racial and ethnic disparities among patients hospitalized for acute cholangitis in the United States. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2023;57(7):731-736.

doi pubmed - Seo YJ, Hadaya J, Sareh S, Aguayo E, de Virgilio CM, Benharash P. National trends and outcomes in timing of ERCP in patients with cholangitis. Surgery. 2020;168(3):426-433.

doi pubmed - Iezzoni LI, Shwartz M, Moskowitz MA, Ash AS, Sawitz E, Burnside S. Illness severity and costs of admissions at teaching and nonteaching hospitals. JAMA. 1990;264(11):1426-1431.

pubmed - Shahian DM, Liu X, Meyer GS, Torchiana DF, Normand SL. Hospital teaching intensity and mortality for acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia. Med Care. 2014;52(1):38-46.

doi pubmed - Mueller SK, Lipsitz S, Hicks LS. Impact of hospital teaching intensity on quality of care and patient outcomes. Med Care. 2013;51(7):567-574.

doi pubmed - Rich EC, Liebow M, Srinivasan M, Parish D, Wolliscroft JO, Fein O, Blaser R. Medicare financing of graduate medical education. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(4):283-292.

doi pubmed - Fishman LE, Bentley JD. The evolution of support for safety-net hospitals. Health Aff (Millwood). 1997;16(4):30-47.

doi pubmed - Ayanian JZ, Weissman JS. Teaching hospitals and quality of care: a review of the literature. Milbank Q. 2002;80(3):569-593.

doi pubmed - Mechanic R, Coleman K, Dobson A. Teaching hospital costs: implications for academic missions in a competitive market. JAMA. 1998;280(11):1015-1019.

doi pubmed - Taylor DH, Jr., Whellan DJ, Sloan FA. Effects of admission to a teaching hospital on the cost and quality of care for Medicare beneficiaries. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(4):293-299.

doi pubmed - Whittle J, Lin CJ, Lave JR, Fine MJ, Delaney KM, Joyce DZ, Young WW, et al. Relationship of provider characteristics to outcomes, process, and costs of care for community-acquired pneumonia. Med Care. 1998;36(7):977-987.

doi pubmed - Zimmerman JE, Shortell SM, Knaus WA, Rousseau DM, Wagner DP, Gillies RR, Draper EA, et al. Value and cost of teaching hospitals: a prospective, multicenter, inception cohort study. Crit Care Med. 1993;21(10):1432-1442.

doi pubmed - Singh S, Purohit T, Aoun E, Patel Y, Carleton N, Mitre M, Morrissey S, et al. Comparison of the outcomes of endoscopic ultrasound based on community hospital versus tertiary academic center settings. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59(8):1925-1930.

doi pubmed - Yazdanpanah O, Mahadevan A, Sharma A, Benjamin DJ, Kalebasty AR. A comparative study of spinal cord compression management in metastatic prostate cancer: Teaching versus non-teaching hospitals in the United States. Cancer Med. 2024;13(1):e6845.

doi pubmed - Pant S, Patel S, Golwala H, Patel N, Pandey A, Badheka A, Agnihotri K, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve replacement complication rates in teaching vs non-teaching centers in the United States. J Invasive Cardiol. 2016;28(2):67-70.

pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Gastroenterology Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.