| Gastroenterology Research, ISSN 1918-2805 print, 1918-2813 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, Gastroenterol Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://gr.elmerpub.com |

Original Article

Volume 000, Number 000, November 2025, pages 000-000

Metabolic Regulatory Mechanism of Gastric Motility by Acetylcholine

Jun Young Leea, i, Hyo-Yung Yunb, i, Dae Hoon Kimb, i, Seung Myoung Sonc, Woong Choid, Hun Sik Kimd, Ki Bae Kime, Seung Heun Kangf, Hahn Jin Jungf, Dong Wook Leef, Wen-Xie Xug, Kyung-Kuk Hwanga, Sang Jin Leeh, Young Chul Kimh, j, Jang-Whan Baea, j

aDepartment of Internal Medicine, College of Medicine, Chungbuk National University (CBNU), Chungbuk 28644, Korea

bDepartment of Surgery, CBNU, Chungbuk 28644, Korea

cDepartment of Pathology, CBNU, Cheongju, Chungbuk 28644, Korea

dDepartment of Pharmacology, College of Medicine, CBNU, Chungbuk 28644, Korea

eDepartment of Internal Medicine, CBNU, Chungbuk 28644, Korea

fDepartment of ENT, CBNU, Chungbuk 28644, Korea

gDepartment of Physiology, College of Medicine, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China

hDepartment of Physiology, College of Medicine, CBNU, Chungbuk 28644, Korea

iThese authors contributed equally to this work.

jCorresponding Authors: Jang-Whan Bae, Department of Internal Medicine, College of Medicine, Chungbuk National University, Cheongju 28644, Korea; Young Chul Kim, Department of Physiology, College of Medicine, Chungbuk National University, Cheongju 28644, Korea

Manuscript submitted July 15, 2025, accepted October 16, 2025, published online November 17, 2025

Short title: Metabolic Regulation by ATP of Stomach

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/gr2063

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Acetylcholine (ACh), a crucial neurotransmitter for gastric contractions, induces triphasic contraction in stomach. However, the precise mechanism of ACh-induced phasic contractions (AiPCs) remains unclear. Recent data suggest the chloride channel (Cl- channel) may be the principal channel for AiPC in the stomach. Previous studies demonstrated that the opening of the ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channel inhibits AiPC. However, it has not been studied whether inhibition of energy metabolism can regulate AiPC in gastric smooth muscles via this channel. This study investigated whether AiPC in gastric smooth muscle are mediated by chloride channels and modulated by KATP channels under conditions of energy metabolism inhibition.

Methods: Isolated gastric smooth muscle strips from mice and humans were used to record isometric contraction. The subunits of Cl- and KATP channels were evaluated by Western blot.

Results: Niflumic acid and 4,4′-diisothiocyanatostilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid (DIDS), known to block the Cl- channel, inhibited AiPC in gastric smooth muscles of mice. Sodium cyanide (NaCN) and dextro-mannitol, which inhibit energy metabolism, reduced AiPC in gastric smooth muscles of mice. NaCN also lowered AiPC in gastric smooth muscles of humans and vasomotion in human arterial smooth muscles. By Western blot, subunits of the KATP and Cl- channels were identified in gastric smooth muscles of mice and arterial smooth muscles of humans.

Conclusions: This is the first study to demonstrate that suppression of energy metabolism reduces AiPC through activation of KATP channels in both murine and human gastric smooth muscle, linking metabolic state to excitatory neurotransmission. Vasomotions in arterial smooth muscles of humans are also decreased by inhibition of energy metabolism.

Keywords: Gastric motility; Calcium-activated chloride channels; ATP-sensitive potassium channels; Acetylcholine-induced phasic contraction; Energy metabolism

| Introduction | ▴Top |

The gastrointestinal (GI) tract stores and transports ingested food to absorb nutrients through the constant contraction and relaxation of GI smooth muscles. The motility of the GI tract is regulated by both the central nervous system and the enteric nervous system [1]. The enteric nervous system comprises millions of neurons and interstitial cells of Cajal (ICCs), which are distributed along the GI wall [2]. ICC within the GI smooth muscle generate spontaneous contractions through pacemaker potentials, which produce slow waves [3, 4]. Through these spontaneous contractions and regulation by the central and enteric nervous systems, the GI tract facilitates peristalsis.

Several mechanisms regulate the spontaneous contractions of the GI tract. Among them, acetylcholine (ACh) plays an essential role as a prominent excitatory neurotransmitter in the GI tract, eliciting a typical three-stage contraction response [5, 6]. These stages include initial contraction, tonic contraction, and phasic contraction which overlaps with tonic contraction. Initial contraction involves the generation of inositol triphosphate within the cell after ACh binds to the cell membrane, which then releases calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR). Tonic contraction is likely associated with phosphorylation processes, among other complex mechanisms. ACh-induced phasic contractions (AiPCs) are known to depend on calcium from external sources, although the specific ion channels responsible for these contractions in humans and mice have not been conclusively identified. Previous studies have reported that nonselective cation channels (NSCCs) contribute to AiPC in smooth muscles of the guinea pig stomach, dog stomach, and rabbit colon [7-9]. Subsequent research has suggested that calcium-activated chloride channels (CaCCs), found in the digestive tract, might play a role [8, 9].

CaCCs function as anion channels in most tissues, opening to allow chloride ions to exit the cell and increase cellular excitability. They are crucial in the development of therapeutic agents for conditions like asthma, hypertension, and pulmonary arterial hypertension [8-11]. In the GI tract, CaCCs critically support the generation of slow waves in Cajal cells [8, 9, 12-14]. Sanders et al (2012) demonstrated that niflumic acid (NFA) and 4,4′-diisothiocyanatostilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid (DIDS) inhibit CaCC in mouse and human Cajal cells, thereby preventing slow wave generation [13]. Previously, Hotta et al (2005) found that DIDS showed inhibitory effects on slow potential and membrane potential induced by ACh [8]. This paper examines the effects of these inhibitors at the tissue level using mouse gastric smooth muscle. In addition, the impairment of murine gastric contraction Ano1 knockout was also reported [9]. Potassium channels (K+ channels) are instrumental in this process. Types of potassium channels in smooth muscles include voltage-gated, calcium-dependent, and ATP-sensitive potassium channels (KATP channels) [14].

KATP channels, initially discovered in the heart and later found essential for regulating insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells [15], open in response to decreased ATP levels and increased ADP levels within the cell. This triggers potassium to exit the cell, diminishing cellular excitability. Drugs such as glibenclamide bind directly to the sulfonylurea receptor (SUR) structure on KATP channels to inhibit them. In the human pancreas, KATP channels comprise Kir6.2 and four SUR1 subunits [16]. Binding of sulfonylurea drugs to the SUR1 structure blocks KATP channels, promoting insulin secretion as though ATP levels were elevated.

In addition to acting on channels, drugs that modulate energy metabolism by mitochondria can change intracellular ATP levels, potentially influencing AiPC in gastric smooth muscle cells. Vasomotion, the rhythmic spontaneous contractions of vascular smooth muscles, plays a crucial role in regulating tissue oxygen supply and may offer protection in pathological conditions such as hypoxia [17]. Our previous study showed that vasomotion in human vascular smooth muscle is suppressed by KATP channel openers and reactivated by glibenclamide [18-20]. This study explores whether inhibiting energy metabolism could reduce spontaneous contractions as a strategy to control vasomotion.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

Tissue preparation for isometric contraction

Mouse gastric antral tissues were extracted and utilized for the experiments. All animal experiments were conducted following ethical approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Chungbuk National University (CBNUA-1419-20-02; CBNUA-1583-21-01; CBNUA-1978-22-02). Human gastric smooth muscle and gastroepiploic artery tissues were obtained from patients undergoing gastric resection surgery at Chungbuk National University Hospital. Tissues from all patients used in the experiments were obtained following approval from the Institutional Review Board for clinical trials and relevant information regarding the experimental procedures (CBNUH2014-12-012) [14, 18, 19, 21-24].

The extracted mouse gastric tissues and human gastric tissues were rinsed in Krebs-Ringer bicarbonate (KRB) solution and pinned with experimental pins onto Sylgard plates to maintain their original shape and length. Mucosal, submucosal, and serosal tissues were removed in KRB solution, and the circular smooth muscle layer was dissected. Mouse gastric smooth muscles were cut to dimensions of 0.1 cm width × 1 cm length, while human gastric smooth muscles were cut to 0.3 cm width × 1.5 cm length, and fixed on a vertical isometric chamber (25 mL). One end of the muscle was fully secured to the fixed end of the measurement device, and the other end was hung on a ring-shaped loop attached to an isometric force transducer (52-9545, Harvard Instruments, London, UK) to measure tension changes [14, 18, 19, 21-24]. The tension transducer was connected to a PowerLab-Data Acquisition System, Charter v5.5 & LabChart Pro software (ADinstruments, Dunedin, New Zealand), and recorded tensions were measured and recorded on an IBM-compatible computer. Data were displayed on a digital oscilloscope and a computer monitor, and data were analyzed using Origin software and pClamp 2023b [14, 18, 19, 21-24].

Human vascular tissues were similarly divided into segments of 1 cm in length after removing connective tissue, and mounted in a ring shape on a tension recording hook to measure the onset of phasic contractions. Each tissue was allowed to recover for 1.5 - 2.0 h and subsequently subjected to stepwise electrical stimulation to induce stable tension. High K+ (50 mM) solution was repetitively administered two times for human vascular tissues and 3 - 4 times for mouse gastric tissues to achieve consistent contraction conditions and measure stable tensions [14, 18, 19, 21-24].

Western blots

Tissues were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen until whole tissue samples were collected, then homogenized in a homogenization buffer (Merck, Burlington, MA, USA) containing 0.01% (v/v) protease inhibitor cocktail. Protein content was measured using a Bradford protein assay tube (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) with bovine serum albumin (BSA) as the standard. Equivalent amounts of solubilized protein were separated by 8% sodium dodecyl-sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) at 100 V for 90 min and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) at 0.25 A for 2 h at 4 °C.

Polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes were blocked overnight at 4 °C with 5% skim milk in tris-buffered saline (TBS) buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl), followed by incubation for 1 h at room temperature with anti-Kir6.1 (invitrogen, CA, USA), anti-Kir6.2 (Millipore, CA, USA), anti-SUR2B antibody (Millipore, CA, USA), anti-SUR2A antibody (Millipore, CA, USA), and anti-TMEM16A antibody (abcam, Dallas, TX, USA), diluted in TBS buffer containing 1% skim milk and 0.1% Tween-20. After washing three times with TBS buffer containing 0.1% Tween-20, membranes were incubated at room temperature for 1 h with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:5,000) diluted in TBS containing 1% skim milk. The secondary antibody used was anti-mouse IgG (FC) secondary antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Membranes were then treated with ECL (ELPIS) reagent for 1 min and subsequently imaged using a Lass 3000 imager (Fujifilm, Minato-ku, Tokyo, Japan) to detect the reaction [14, 22, 23].

Reagents

We used a KRB solution containing NaCl 122 mM, KCl 4.7 mM, MgCl2 1 mM, CaCl2 2 mM, NaHCO3 15 mM, KH2PO4 0.93 mM, and glucose 11 mM (pH 7.3 - 7.4, bubbled with 5% CO2/95% O2). For the high K+ (50 mM) solution, equimolar Na+ was replaced with potassium. The experimental solution was pre-warmed to 36 °C and continuously bubbled with 5% CO2/95% O2 prior to replacement. Tension responses to high K+ stimulation were recorded for 10 min, and measurements were taken at the 10-min mark. BayK 8644 was administered 12 - 20 min before each experiment to stabilize responses before recording. The reagent used in the experiment was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and an equal amount of DMSO was administered to the control group during the experiment. All reagents used in this study were purchased from Merck (Burlington, MA, USA) [14, 18, 19, 21-24].

Statistical analysis

The data are expressed as means ± standard deviation of the mean (e.g., mean ± SD). Student’s t-test was employed to assess statistical significance. P-values less than 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant as P < 0.05. Experimental number (n) means individual independent experiment. Analysis of each contraction of gastric muscle and artery was performed as follows: Each contractile response was detected and analyzed when each response reached steady state. ACh-induced tri-phasic contraction was compared to that from spontaneous basal contraction. In the case of pretreatment experiment, the effects of each additive treatment were compared to that of steady state of pretreated contraction. In the case of vasomotion analysis, the same analysis was applied.

| Results | ▴Top |

Spontaneous contractions and AiPC in mouse gastric smooth muscle

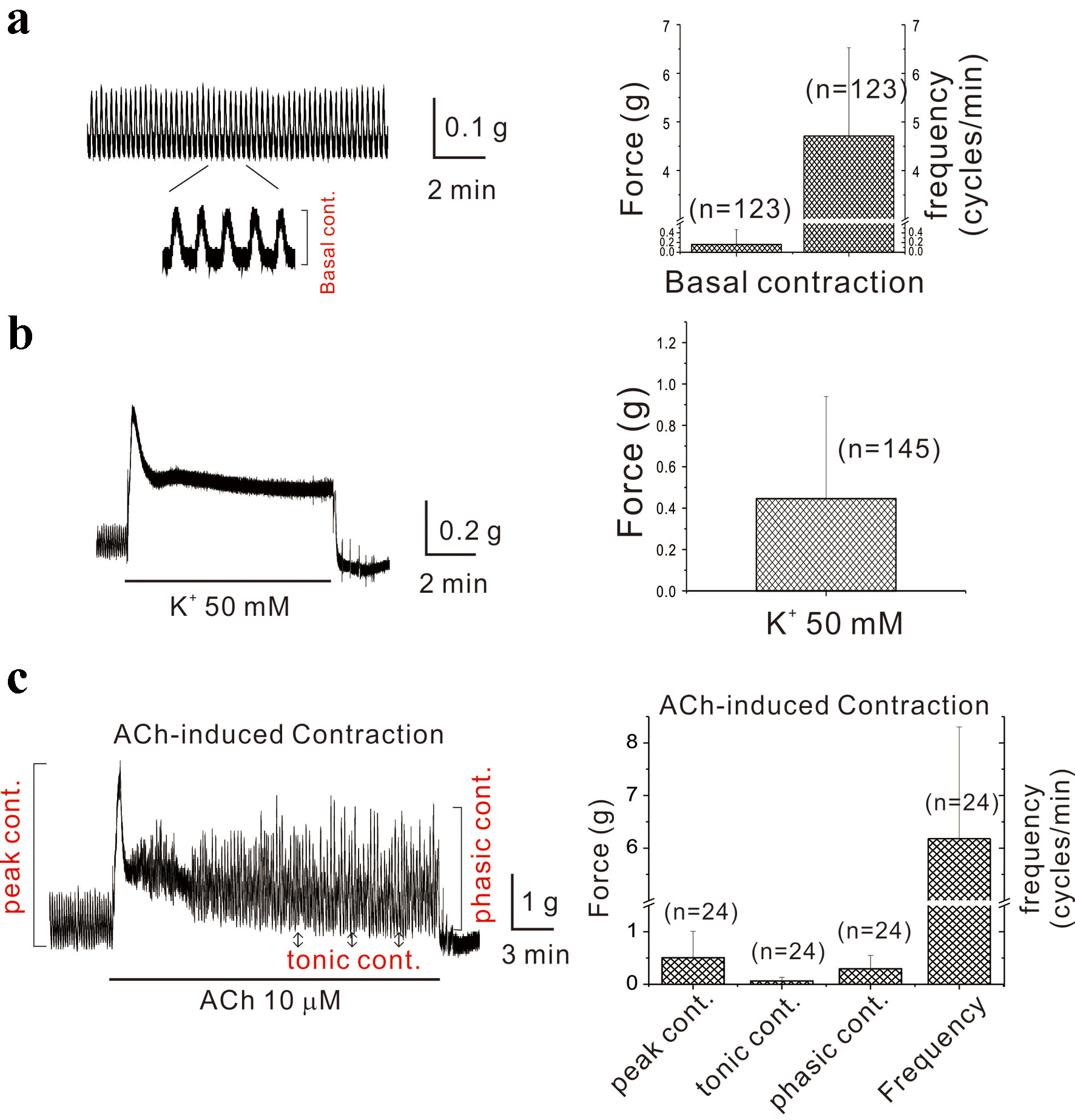

As depicted in Figure 1a, spontaneous contractions in mouse gastric smooth muscle displayed tensions of 0.20 ± 0.31 g and frequencies of 4.70 ± 1.82 cycles/min (n = 123). The muscle exhibited tonic contractions of 0.45 ± 0.49 g upon application of 50 mM K+ (n = 145, Fig. 1b). Administration of ACh resulted in AiPC. Following the administration of ACh (10 µM), depicted in Figure 1c, initial contractions were noted, succeeded by a combination of tonic and phasic contractions. Each component of AiPC was indicated in right panel of c (red color). These initial and tonic contractions were 0.50 ± 0.50 g and 0.06 ± 0.07 g, respectively, while phasic contractions were 0.30 ± 0.26 g (n = 24).

Click for large image | Figure 1. Spontaneous contractions of mouse gastric smooth muscle and acetylcholine-induced periodic contractions. (a) Spontaneous contraction of mouse gastric smooth muscle is demonstrated with an observed force of 0.2 g and a frequency of 4.7 cycles/min (n = 123). The component of basal contraction is indicated as expanded trace. In (b), gastric smooth muscle exhibited a tonic contraction (0.45 g) induced by 50 mM K+ (n = 145). The administration of ACh resulted in AiPC. Immediately following ACh administration (10 µM), as shown in (c), initial contractions were noted, accompanied by overlapping tonic and phasic contractions. The initial and tonic contractions measured 0.50 and 0.06 g, respectively, while phasic contractions were 0.30 g (n = 24). The components of initial, tonic, and phasic contractions are indicated in left panel of (c). ACh: acetylcholine; AiPC: acetylcholine-induced phasic contractions. |

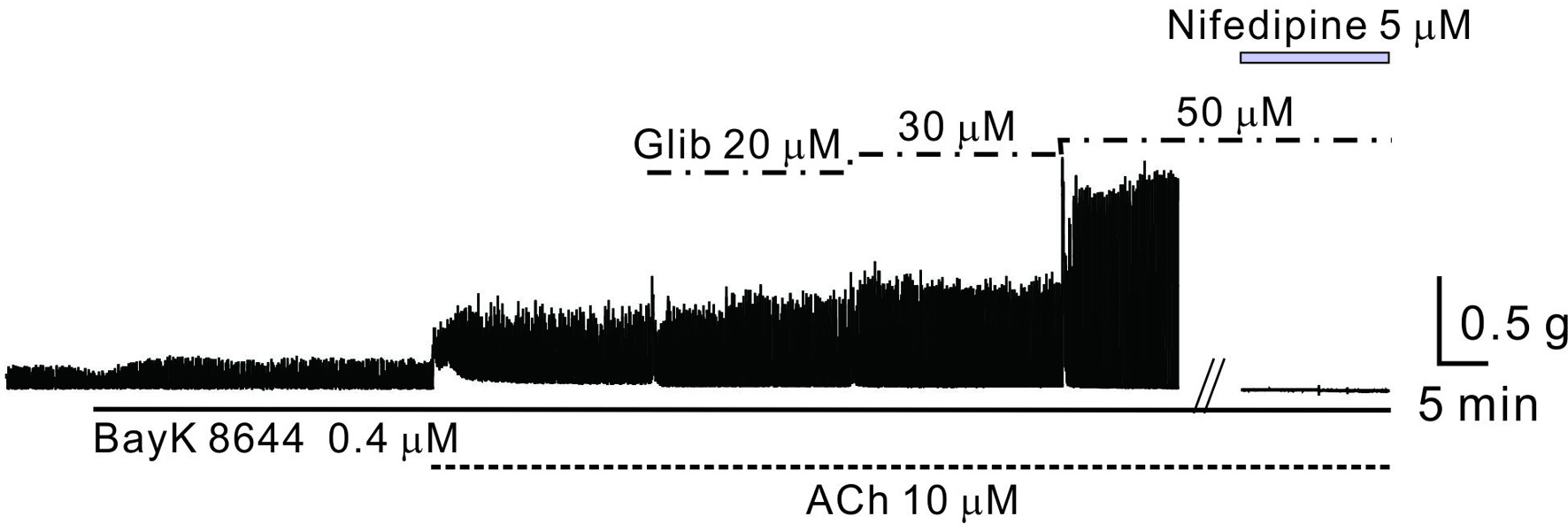

Administration of BayK 8644 followed by ACh, KATP channel blocker, and calcium channel blocker in mouse gastric smooth muscle

Smooth muscle contraction is driven by calcium influx, and to enhance contractility, we verified the response after pretreatment with BayK 8644, a dihydropyridine-sensitive voltage-dependent L-type calcium channel agonist. Following this pretreatment and induction of AiPC, significant enhancement in contractility was observed with glibenclamide administration. This response ceased with nifedipine, a membrane voltage-dependent calcium channel blocker (Fig. 2). Although unreported, the potentiation of AiPC by glibenclamide was minimal in the absence of BayK 8644 pretreatment. This implies that KATP channel activity level may correlate with intracellular calcium levels.

Click for large image | Figure 2. The role of Ca2+ and ATP-sensitive potassium channels in AiPC of mouse gastric smooth muscle. The effects of glibenclamide on AiPC in the presence of BayK 8644 and ACh were examined. AiPC was induced by ACh in the presence of BayK 8644 and significantly amplified following the application of glibenclamide (50 - 80 µM). ACh: acetylcholine; AiPC: acetylcholine-induced phasic contractions. |

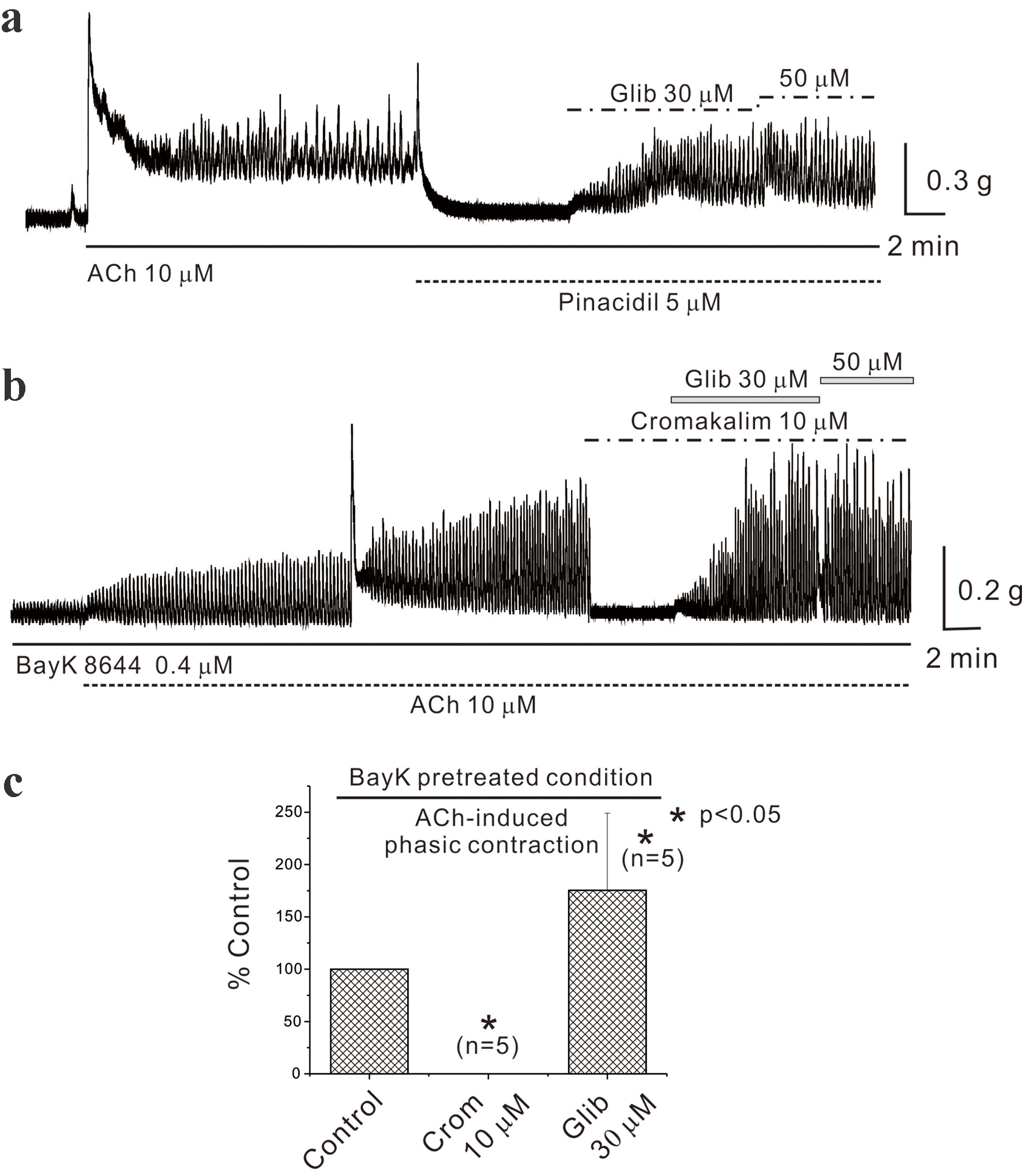

Effects of KATP channel opener and blocker on AiPC in mouse gastric smooth muscle

AiPC was recorded during the administration of drugs targeting KATP channels. As illustrated in Figure 3a, AiPC decreased with the administration of the KATP channel opener pinacidil (5 µM) and was reinstated by the blocker glibenclamide. Subsequent experiments involved pretreatment with BayK 8644. Figure 3b shows that AiPC was completely abolished following the administration of another KATP channel opener, cromakalim (10 µM), and was restored with subsequent glibenclamide treatment. The data are summarized in Figure 3c.

Click for large image | Figure 3. Effects of ATP-sensitive potassium channel opener and blocker in mouse gastric smooth muscle. (a) It demonstrates the inhibition of AiPC by pinacidil (5 µM) and its restoration by glibenclamide in mouse gastric smooth muscle. (b) Cromakalim also inhibited AiPC in the presence of BayK 8644 in a glibenclamide-sensitive manner. Data were summarized in (c) (n = 5). Asterisks show a statistical significance (*P < 0.05). ACh: acetylcholine; AiPC: acetylcholine-induced phasic contractions. |

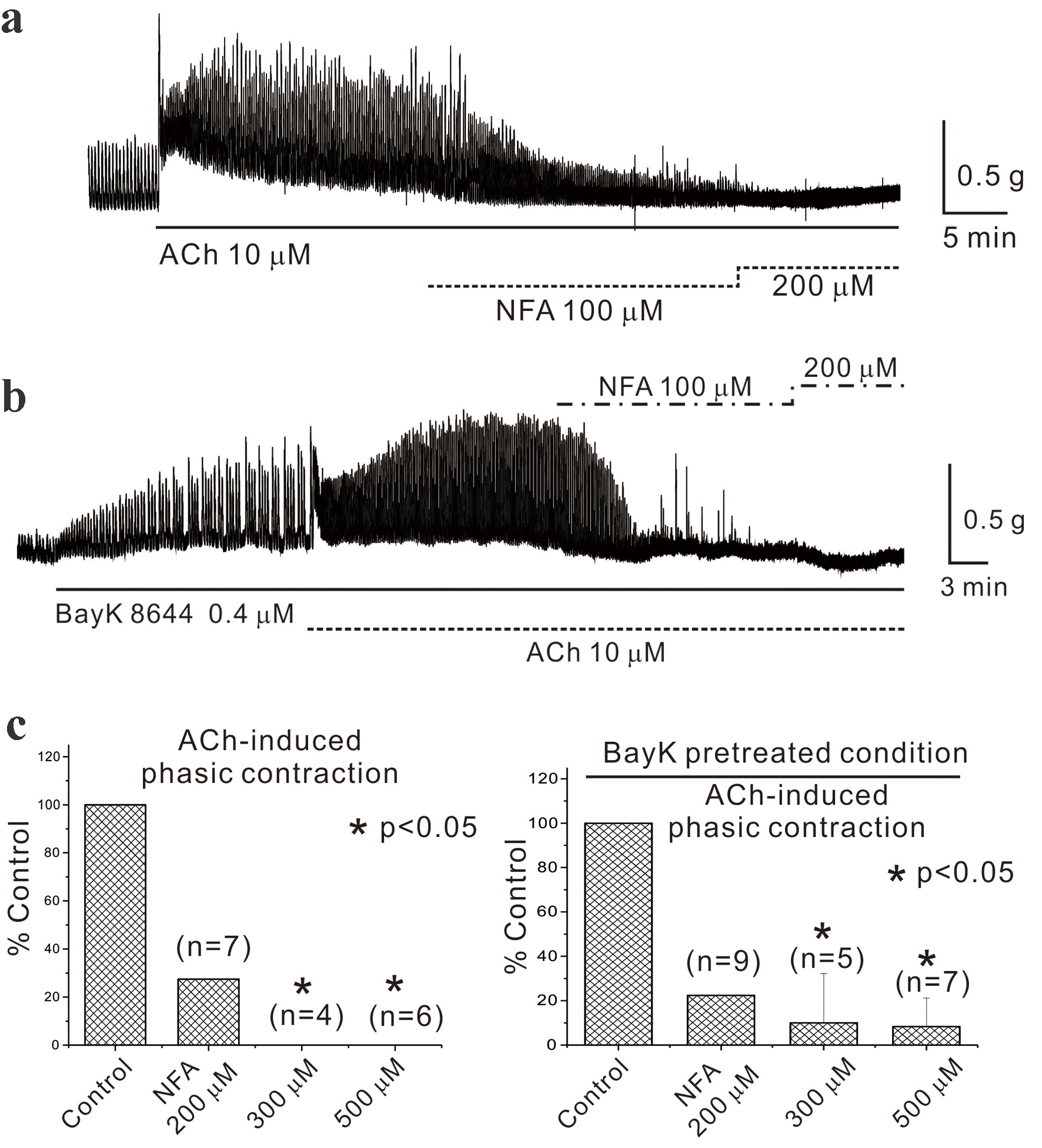

Effects of chloride channel blockers on AiPC in mouse gastric smooth muscle

Recording of AiPC induced by ACh (10 µM) in mouse gastric smooth muscle occurred while examining blockers active on CaCC, specifically NFA and DIDS. Figure 4a and c (left panel) reveals that NFA (200, 300, and 500 µM) reduced AiPC to 28.0±72.6% (n = 7, P > 0.05), 0% (n = 4, P < 0.05), and 0% (n = 6, P < 0.05) of the control, respectively. Asterisks show a statistical significance (P < 0.05). No detailed results were provided for DIDS, but it similarly reduced AiPC to 67.0±40.4% (n = 6, P > 0.05) and 33.0±25.9% (n = 10, P < 0.05) of the control at 300 and 500 µM, respectively (data not shown).

Click for large image | Figure 4. Administration of chloride channel blocker in mouse gastric smooth muscle. (a) and (c, left panel) It reveals that NFA (200, 300, and 500 µM) reduced acetylcholine-induced phasic contractions to 28.0±72.6% (n = 7, P > 0.05), 0% (n = 4, P < 0.05), and 0% (n = 6, P < 0.05) of the control, respectively. Asterisks show a statistical significance (*P < 0.05). In the subsequent step, BayK 8644 (0.4 µM), utilized in previous experiments, was pretreated before administering NFA. As depicted in (b) and (c, right panel), NFA (200, 300, and 500 µM) inhibited AiPC to 22.0±46.3% (n = 9, P > 0.05), 10.0±22.2% (n = 5, P < 0.05), and 8.0±12.8% (n = 7, P < 0.05) of the control, respectively. The data are summarized in Figure 3c. ACh: acetylcholine; AiPC: acetylcholine-induced phasic contractions; NFA: niflumic acid. |

In the subsequent step, BayK 8644 (0.4 µM), utilized in previous experiments, was pretreated before administering NFA. As depicted in Figure 4b and c (right panel), NFA (200, 300, and 500 µM) inhibited AiPC to 22.0±46.3% (n = 9, P > 0.05), 10.0±22.2% (n = 5, P < 0.05), and 8.0±12.8% (n = 7, P < 0.05) of the control, respectively.

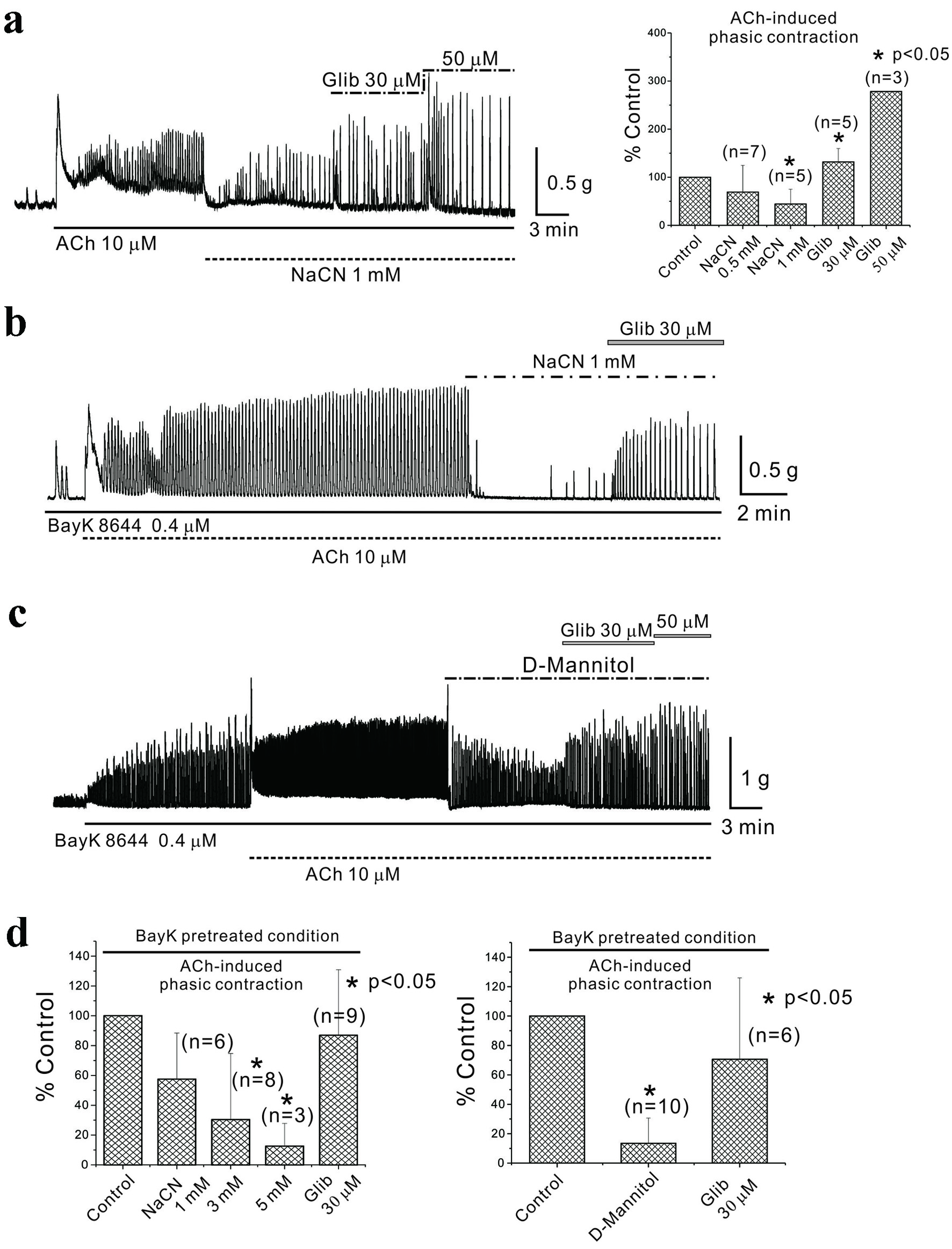

Effects of inhibition of energy metabolism on AiPC in mouse gastric smooth muscle

AiPC induction in mouse gastric smooth muscle is regulated by KATP channels, implying that it may be indirectly regulated by inhibiting energy metabolism. To test this hypothesis, we designed experiments where AiPC inhibition by energy metabolism inhibitors was reversed by KATP channel blockers such as glibenclamide. Energy metabolism was inhibited by administering sodium cyanide (NaCN) and replacing extracellular glucose with impermeable dextro-mannitol (D-mannitol). Figure 5a (left panel) displays AiPC induction by ACh administration, demonstrating that NaCN (0.5 and 1 mM) reduced AiPC to 69.0±55.4% (n = 7, P > 0.05) and 44.0±30.7% (n = 5, P < 0.05) of the control, respectively, and these inhibitions were reversed by glibenclamide (30 and 50 µM) to 132.0±27.9% (n = 5, P < 0.05) and 278.0% (n = 3), respectively. These data were summarized in Figure 5a (right panel). The experiments continued post-pretreatment with BayK 8644 (0.4 µM). Figure 5b reveals that NaCN (1, 3, and 5 mM) suppressed AiPC to 58±31% (n = 6, P > 0.05), 30±44.3% (n = 8, P < 0.05), and 13±15.3% (n = 3, P < 0.05) of the control, respectively. AiPC inhibition by D-mannitol is shown in Figure 5c, reducing AiPC to 14.0±17.2% of the control (n = 10, P < 0.05), and this inhibition was offset by glibenclamide to 71.0±55.3% (n = 6, P < 0.05). Data are summarized in Figure 5d.

Click for large image | Figure 5. Inhibition of energy metabolism in mouse gastric smooth muscle. (a) NaCN administration inhibited AiPC, which were restored by glibenclamide. NaCN (0.5 mM and 1 mM) reduced AiPC to 69.0±55.4% (n = 7, P > 0.05) and 44.0±30.7% (n = 5, P < 0.05) of the control, respectively, and these inhibitions were reversed by glibenclamide (30 and 50 µM) to 132.0±27.9% (n = 5, P < 0.05) and 278.0% (n = 3), respectively. These data were summarized in (a) (right panel). Asterisks show a statistical significance (*P < 0.05). In (b) and (c), AiPC in the presence of BayK 8644 was studied. (b) It reveals that NaCN (1, 3, and 5 mM) suppressed AiPC to 58±31% (n = 6, P > 0.05), 30±44.3% (n = 8, P < 0.05), and 13±15.3% (n = 3, P < 0.05) of the control, respectively. In (c), AiPC inhibition by D-mannitol is shown. AiPC was reduced to 14.0±17.2% of the control (n = 10, P < 0.05), and this inhibition was offset by glibenclamide to 71.0±55.3% (n = 6, P < 0.05). Data were summarized in (d). Asterisks show a statistical significance (*P < 0.05). ACh: acetylcholine; AiPC: acetylcholine-induced phasic contractions; NaCN: sodium cyanide. |

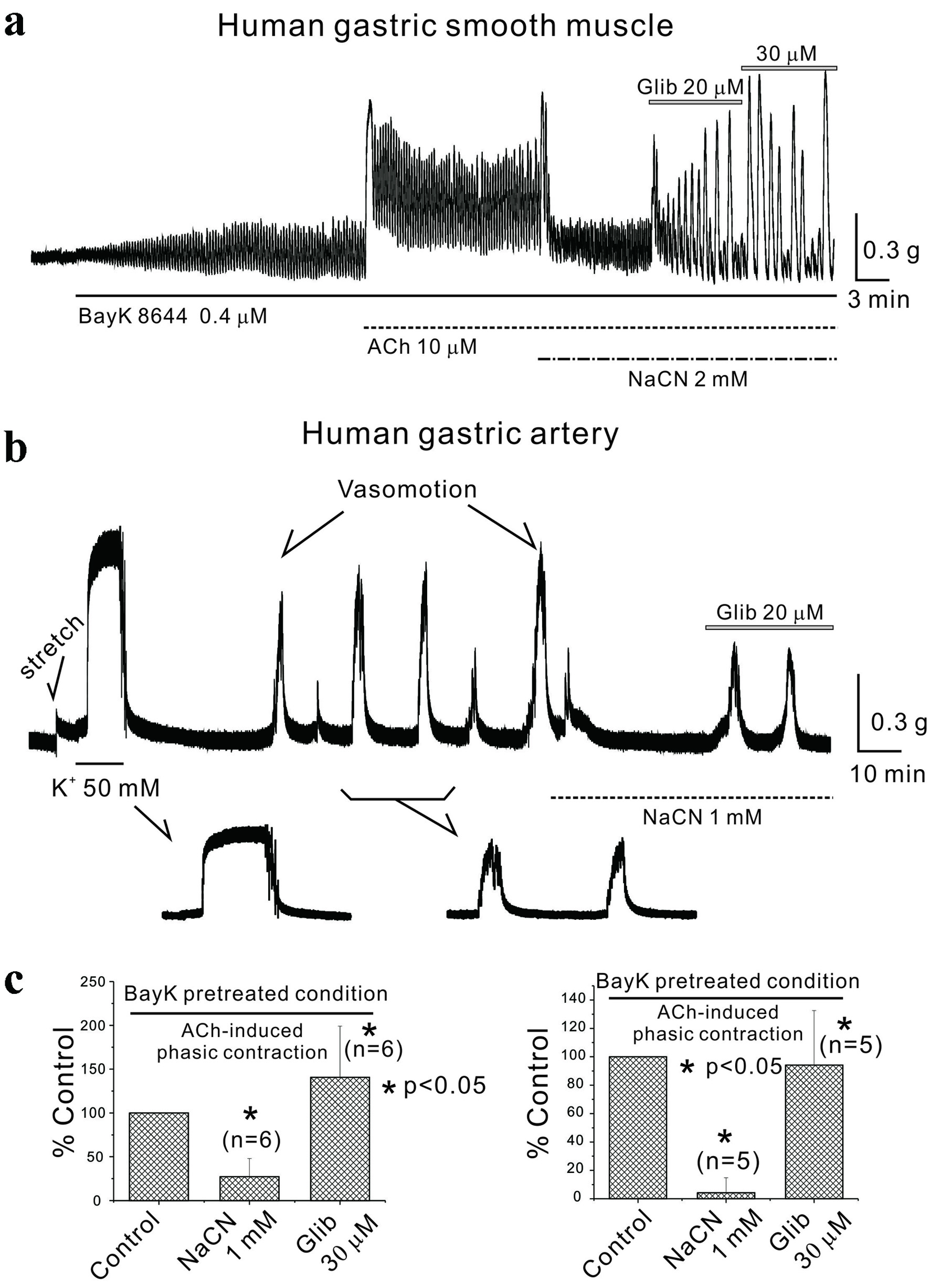

Inhibition of energy metabolism in human gastric smooth muscle and human gastroepiploic artery

The aforementioned studies were expanded to examine AiPC in human gastric smooth muscle and spontaneous contractions (vasomotion) in human vascular smooth muscle. In Figure 6a, using human gastric smooth muscle post-pretreatment with BayK 8644 (0.4 µM), AiPC was measured, and NaCN (1 mM) was administered, reducing AiPC to 27.0±20.7% of the control, which was then elevated to 141.0±58.4% with the administration of glibenclamide (n = 6, P < 0.05; c (left panel)). Even though data not shown in here, AiPC in human gastric smooth muscle was also inhibited by application of NFA (200 - 500 µM). In human gastroepiploic artery smooth muscle as shown in Figure 6b, vasomotion (spontaneous contractions) were recorded and inhibited by NaCN (1 mM) to 4.0±10.5%, later restored to 94.0±38.4% by glibenclamide (n = 5, P < 0.05; c (right panel)). Both sets of data are summarized in Figure 6c.

Click for large image | Figure 6. Inhibition of energy metabolism in human gastric smooth muscle and human arterial smooth muscle. (a) In human gastric smooth muscle, following BayK 8644 pretreatment, NaCN inhibited AiPC, which were restored by glibenclamide. NaCN (1 mM) reduced human AiPC in the presence of BayK 8644 to 27.0±20.7% of the control, which was then elevated to 141.0±58.4% with the administration of glibenclamide (n = 6, P < 0.05; c (left panel)). (b) Vasomotion was observed in human arterial smooth muscle and was inhibited by sodium cyanide and restored by glibenclamide. NaCN (1 mM) reduced vasomotion (spontaneous contractions) to 4.0±10.5% of the control, which was restored to 94.0±38.4% by glibenclamide (n = 5, P < 0.05; c (right panel)). All data were summarized in (c). Asterisks show a statistical significance (*P < 0.05). ACh: acetylcholine; AiPC: acetylcholine-induced phasic contractions; NaCN: sodium cyanide. |

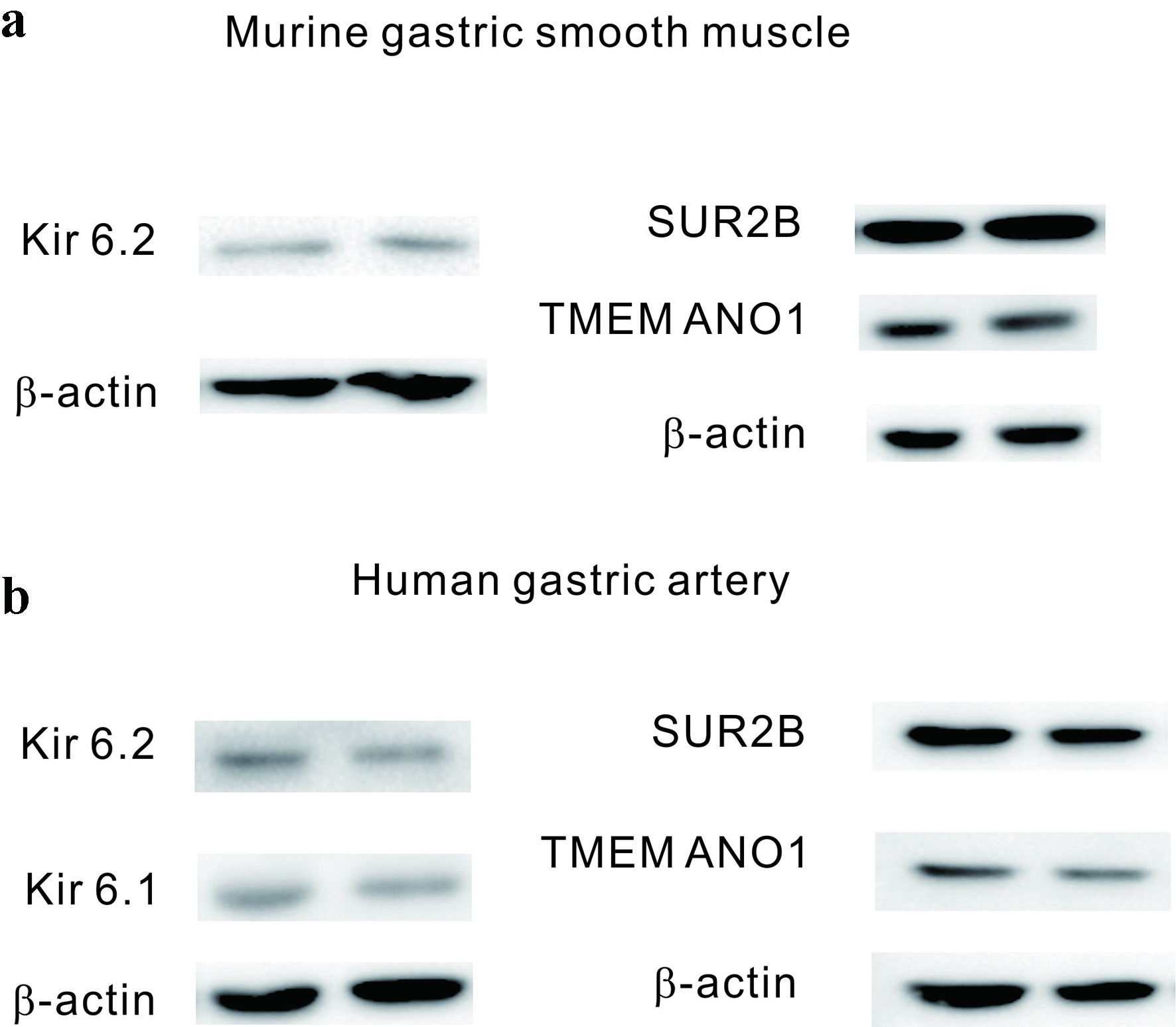

Western blot analysis of mouse gastric smooth muscle and human vascular smooth muscle

Through the aforementioned studies, we explored the regulatory potential of KATP channels in mouse gastric smooth muscle and in human gastric and vascular smooth muscles via EM inhibition. As a conclusive step, Western blot analysis was performed to identify the target proteins of KATP channels and CaCC, central to our experiments, in both mouse gastric smooth muscle and human vascular smooth muscle.

In Figure 7a, mouse gastric smooth muscle disclosed the structural proteins of KATP channels as Kir6.2 and SUR2, whereas Kir6.1 was not detected. Similarly, in human vascular smooth muscle, the components of KATP channels were identified as Kir6.2, Kir6.1, and SUR2 in human gastric vessels. TMEM16A (ANO1), the structural protein of CaCC, was observed in both mouse gastric smooth muscle and human vascular smooth muscle tissues.

Click for large image | Figure 7. Western blot analysis of mouse gastric smooth muscle and human arterial smooth muscle. (a) In mouse gastric smooth muscle, the component proteins of KATP channels, SUR2B, and Kir6.2, were identified, along with TMEM16A, the component protein of calcium-activated chloride channels. (b) In human arterial smooth muscle, the component proteins of KATP channels, SUR2B, Kir6.1, and Kir6.2, were identified, as well as TMEM16A, the component protein of calcium-activated chloride channels. KATP channels: ATP-sensitive potassium channels. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

This study confirmed the presence and/or function of CaCC in smooth muscles of mouse and human stomachs. At the tissue level, inhibiting energy metabolism suppressed AiPC in mouse and human gastric smooth muscles through KATP channel. Vasomotion of human gastroepiploic artery smooth muscle was also inhibited under these conditions.

Since the fundus of stomach functions to store food through its relaxation, its primary motor function is relaxation. Conversely, as the phasic contractions of the stomach increase from the upper body to the pylorus, the function of crushing ingested food is known to become more pronounced. As with the above functions of stomach, the motor patterns and/or functions of the stomach have been reported to show regional differences. In human samples, isometric force in response to the exogenous application of ACh displayed regional differences. In the gastric antrum, ACh showed three phasic contractions such as the initial peak contraction, contractile frequency, and amplitude of contraction after ACh exposure [25]. In the corpus and fundus, however, ACh produced initial peak contraction and tonic contraction. Among the contraction responses in the gastric system, one of the most significant is contraction induced by ACh released at nerve terminals. Strong, continuous phasic contractions throughout the stages of digestion continually consume energy; consequently, metabolic changes are expected to influence and regulate gastric motility. When ACh binds to muscarinic receptors on the cell membrane of smooth muscle of the GI tract, an intracellular signaling cascade is induced [26, 27]. It results in the breakdown of intracellular G proteins and the production of inositol phosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DAG). IP3 then releases Ca2+ from the SR while DAG activates protein kinase C [26, 28]. These cellular responses to ACh are evident in three stages of tissue reaction: initial contraction, followed by tonic contraction, which overlaps with phasic contraction (Fig. 2) [28]. Initially, ACh’s binding to the cell membrane and subsequent generation of IP3 prompts the release of Ca2+ from the intracellular SR. Phasic contraction depends on continuous extracellular Ca2+ influx, while tonic contraction likely involves phosphorylation steps [14].

In smooth muscle, the utilized energy comes from the hydrolysis of ATP, specifically from the energy released when the terminal phosphate group of ATP is cleaved. Within cells, ATP is hydrolyzed to ADP, and the ADP/ATP ratio continuously fluctuates. In the context of cellular energy metabolism, targets that detect these changes and elicit responses include KATP channels, whose opening and closing are regulated by the intracellular ADP/ATP ratio. When intracellular ATP levels are low, these channels open, allowing potassium ions to exit the cell, thereby reducing excitability. Conversely, under conditions of high ATP, these channels close, thereby increasing the cell’s excitability [29-31]. As illustrated in Figure 3a and b, pinacidil and cromakalim inhibited AiPC in a glibenclamide-sensitive manner. Notably, AiPC in the presence of BayK 8644 was substantially enhanced by glibenclamide application (Fig. 2). This suggests that KATP channel activation may also be linked to other intracellular factors such as calcium channel and/or intracellular concentration. Currently, the precise mechanisms remain unclear, but further investigations are planned.

In the smooth muscle of the GI tract, phasic contractions induced and sustained by ACh during digestion could cause cellular energy levels to fluctuate. To explore this, Figure 2 shows that the administration of glibenclamide, a KATP channel blocker, during AiPC resulted in sustained contractions. These findings imply that energy metabolism and the activation of KATP channels might play an important role in maintaining sustained AiPC. Specifically, as depicted in Figure 3, consistent responses were observed when AiPC was exposed to both activators and blockers of KATP channels, such as pinacidil and glibenclamide, respectively. This highlights the potential functional role of KATP channels in this process. Figure 3a confirms the influence of KATP channels on contraction responses to ACh in mouse gastric tissue following the administration of pinacidil. Figure 3b and c indicates similar responses under conditions of enhanced contraction with prior treatment of BayK 8644 (0.4 µM) to activate intracellular Ca2+ influx, subsequently confirmed with cromakalim. These findings collectively point to the presence of metabolically regulated KATP channels that play a functional role during strong contractions induced by Ca2+ influx and ACh in mouse gastric smooth muscle.

Based on the results presented in Figure 5a, b, and d (right panel), studies on AiPC and BayK 8644-pretreated AiPC in mouse stomachs were performed, observing their responses to metabolic inhibitors. NaCN, a known metabolic inhibitor, inhibited both AiPC and BayK 8644-pretreated AiPC. This inhibition was reversed by glibenclamide. These responses suggest that activation of KATP channels, which occurs when intracellular energy is suppressed and ATP production is inhibited, reduces tissue excitability and thereby inhibits contraction. Specifically, as illustrated in Figures 5d and 6c (right panel), when extracellular glucose was completely replaced with impermeable D-mannitol, BayK 8644-pretreated AiPCs were inhibited, and recovery occurred with the administration of glibenclamide (data not shown). Overall, these results collectively indicate that phasic contractions induced by ACh in mouse stomachs may be regulated in association with metabolic changes. This association was established under conditions of metabolic inhibition, demonstrating consistent relevance even under altered metabolic states.

The next step involved verifying whether similar responses observed in mouse stomachs could also be induced in human gastric smooth muscle. Figure 6a depicts the effects of administering ACh to human gastric smooth muscle tissue, both with and without pretreatment with BayK 8644. When ACh (10 µM) was administered, it induced initial contraction followed by tonic contraction and overlapped phasic contraction too [14]. The administration of the metabolic inhibitor NaCN inhibited AiPC, but it was reversed by glibenclamide (Fig. 6a). Although not shown in the results, similar responses in human gastric smooth muscle involved the disappearance or suppression of AiPC contraction frequency by mannitol, which was restored upon glibenclamide administration (n = 4). Figure 6b documents vasomotion (spontaneous contraction) in human gastric vessels, which responded to NaCN administration. Vasomotion is linked to the rhythmic changes in lumen diameter of blood vessels. It was first described in 1852 by bat circulation and can give rise to flow into each organ [32, 33]. Vasomotion has been noted as a common phenomenon in several vessels including arteries of diverse organs [33]. In our previous study, vasomotion of human gastric artery is sensitive to TMEM16A CaCC [18]. As the wall of GI tract moves, its blood vessels are simultaneously stimulated by compression and rarefaction (and/or relaxation). During this process, the blood vessels of the digestive tract are expected to undergo a series of processes to maintain a constant blood flow by appropriately responding to the movement of gastric smooth muscle. From this interlinked perspective, we aimed to study the role of energy metabolism and chloride ion channels in the recently reported regulation of gastric vasomotion, along with changes in GI smooth muscle motility. In this study, vasomotion in these vessels was inhibited by NaCN and restored by glibenclamide. However, vasomotion in human gastric vessels was not restored by glibenclamide after D-mannitol administration (data not shown). These findings suggest that various metabolic regulations may play a role in modulating phasic contractions in both mouse and human gastric smooth muscle, as well as in spontaneous vasomotion in human gastric vessels.

In the final stages, research focused on the mechanisms driving phasic contractions in mouse gastric smooth muscle induced by ACh. Figure 4 confirms the potential regulation of AiPC and BayK 8644-pretreated AiPC by chloride ion channels. Specific to this study, administering NFA, a recognized blocker of chloride ion channels, at concentrations of 200, 300, and 500 µM resulted in inhibiting AiPC by 28%, 0%, and 0%, respectively. Although not displayed in the results, another chloride ion channel blocker, disodium salt (DIDS, at concentrations of 300 and 500 µM), also inhibited AiPC by 67% and 33%, respectively. These findings led to the conclusion that AiPC in mouse stomachs might be linked with the activation of chloride ion channels. Historically, ACh was known to activate nonselective cation channels in guinea pig gastric smooth muscle, but recent studies have highlighted the significant role of chloride ion channels in mouse ICC and smooth muscle [8, 9, 26]. Notably, NFA utilized in this investigation to differentiate chloride ion channels involved in phasic contractions in GI smooth muscle is reported to inhibit not only chloride ion channels based on concentration but also calcium-dependent potassium channels (KCa channels) [17]. Additionally, DIDS has been noted to block TMEM16A chloride ion channels in specific ion channel experiments, effective at a blocking concentration as low as 10 µM, with a half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of approximately 30 µM, with maximum inhibition observed at around 100 µM [17]. In this study, the concentrations of NFA and DIDS implemented to suppress phasic contractions in gastric smooth muscle exceeded 100 µM, signifying that these levels may act efficiently at tissue levels compared to concentrations applied directly to single ion channels in cells. Furthermore, instances were noted where lower concentrations actually enhanced phasic contractions, suggesting the participation of other ion channels inhibited by NFA or DIDS.

To further validate the previous findings and explore the presence of these ion channels at the molecular level, Western blotting experiments were conducted. These experiments aimed to confirm the presence of molecular components of KATP channels, including Kir6.1, Kir6.2, and TMEM16A (ANO1), a representative chloride ion channel recently identified in the GI tract, in mouse gastric smooth muscle and human gastric vessel smooth muscle. As illustrated in Figure 7a, in mouse gastric smooth muscle, molecular components such as Kir6.2 and SUR2 of KATP channels were detected, whereas Kir6.1 was absent (Supplementary Material 1, gr.elmerpub.com). In contrast, in human gastric vessel smooth muscle, molecular components of KATP channels, including Kir6.2, Kir6.1, and SUR2, were identified [14]. Finally, the expression of TMEM16A (ANO1) in human gastric muscle was also observed in Supplementary Material 2B (gr.elmerpub.com).

These experiments confirmed that KATP channels are present in both mouse and human gastric smooth muscle. They suggested that activation of KATP channels under conditions of impaired cellular energy metabolism or reduced energy availability could induce smooth muscle relaxation. KATP channels are found not only in the GI tract but also in the pancreas, heart, and brain [34]. Given their described characteristics, KATP channels can be activated and open under pathological conditions such as hypoxia and ischemia, thus reducing cellular excitability and potentially safeguarding cells from further damage [35]. Animal studies have indicated that the knockout of Kir6.2, a component of brain KATP channels, exacerbates the severity of ischemic infarction, whereas overexpression mitigates neuronal injury caused by ischemia [36]. Therefore, additional research is warranted to determine whether KATP channels could be harnessed to decrease cellular damage in hypoxic or ischemic conditions.

From above results, we suggested role of metabolism and TMEM16A (ANO1) in the regulation of gastric motility in mouse and human stomach.

| Supplementary Material | ▴Top |

Suppl 1. Molecular data of murine gastric smooth muscle, compatible to Figure 7.

Suppl 2. Molecular data of human gastric artery (A) and human gastric muscle (B) showing TEME ANO1 expression respectively.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

This research was supported by a grant of the MD-PhD/Medical Scientist Training Program through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest exists for this study.

Informed Consent

Informed consent has been obtained.

Author Contributions

Jun Young Lee, Hyo-Yung Yun, and Dae Hoon Kim: operation and tissue, experiments, analysis, and writing - review, editing, and correction. Seung Myeung Son, Woong Choi, and Young Chul Kim: experiments, analysis, and writing - review, editing, and correction. Hun Sik Kim: analysis and writing - review, editing, and correction. Ki Bae Kim, Kyung-Kuk Hwang, Jang Whan Bae, Seung Heun Kang, Han Jin Jung, Dong Wook Lee, Wen-Xie Xu, and Sang Jin Lee: writing - review, editing, and correction.

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

ACh: acetylcholine; AiPC: ACh-induced phasic contractions; CaCC: calcium-activated chloride channels; DAG: diacylglycerol; DIDS: 4,4′-diisothiocyanatostilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid; D-mannitol: dextro-mannitol; GI: gastrointestinal; ICC: interstitial cells of Cajal; IP3: inositol phosphate; KATP channels: ATP-sensitive potassium channels; KRB: Krebs-Ringer bicarbonate; NaCN: sodium cyanide; NFA: niflumic acid; NSCC: nonselective cation channels; SR: sarcoplasmic reticulum; TBS: tris-buffered saline

| References | ▴Top |

- Furness JB. The enteric nervous system and neurogastroenterology. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;9(5):286-294.

doi pubmed - Thuneberg L. Interstitial cells of Cajal: intestinal pacemaker cells? Adv Anat Embryol Cell Biol. 1982;71:1-130.

pubmed - Huizinga JD, Thuneberg L, Kluppel M, Malysz J, Mikkelsen HB, Bernstein A. W/kit gene required for interstitial cells of Cajal and for intestinal pacemaker activity. Nature. 1995;373(6512):347-349.

doi pubmed - Kim YC, Suzuki H, Xu WX, Hashitani H, Choi W, Yun HY, Park SM, et al. Voltage-dependent Ca current identified in freshly isolated interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC) of Guinea-pig stomach. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2008;12(6):323-330.

doi pubmed - Golenhofen K, Weiser HF, Siewert R. Phasic and tonic types of smooth muscle activity in lower oesophageal sphincter and stomach of the dog. Acta Hepatogastroenterol (Stuttg). 1979;26(3):227-234.

pubmed - Vogalis F, Sanders KM. Cholinergic stimulation activates a non-selective cation current in canine pyloric circular muscle cells. J Physiol. 1990;429:223-236.

doi pubmed - Kim SJ, Ahn SC, So I, Kim KW. Quinidine blockade of the carbachol-activated nonselective cationic current in guinea-pig gastric myocytes. Br J Pharmacol. 1995;115(8):1407-1414.

doi pubmed - Hotta A, Kim YC, Nakamura E, Kito Y, Yamamoto Y, Suzuki H. Effects of inhibitors of nonselective cation channels on the acetylcholine-induced depolarization of circular smooth muscle from the guinea-pig stomach antrum. J Smooth Muscle Res. 2005;41(6):313-327.

doi pubmed - Hwang SJ, Pardo DM, Zheng H, Bayguinov Y, Blair PJ, Fortune-Grant R, Cook RS, et al. Differential sensitivity of gastric and small intestinal muscles to inducible knockdown of anoctamin 1 and the effects on gastrointestinal motility. J Physiol. 2019;597(9):2337-2360.

doi pubmed - Raut SK, Singh K, Sanghvi S, Loyo-Celis V, Varghese L, Singh ER, Gururaja Rao S, et al. Chloride ions in health and disease. Biosci Rep. 2024;44(5).

doi pubmed - Liu Y, Liu Z, Wang K. The Ca(2+)-activated chloride channel ANO1/TMEM16A: An emerging therapeutic target for epithelium-originated diseases? Acta Pharm Sin B. 2021;11(6):1412-1433.

doi pubmed - Huizinga JD, Zhu Y, Ye J, Molleman A. High-conductance chloride channels generate pacemaker currents in interstitial cells of Cajal. Gastroenterology. 2002;123(5):1627-1636.

doi pubmed - Sanders KM, Zhu MH, Britton F, Koh SD, Ward SM. Anoctamins and gastrointestinal smooth muscle excitability. Exp Physiol. 2012;97(2):200-206.

doi pubmed - Lee SE, Kim DH, Son SM, Choi SY, You RY, Kim CH, Choi W, et al. Physiological function and molecular composition of ATP-sensitive K(+) channels in human gastric smooth muscle. J Smooth Muscle Res. 2020;56(0):29-45.

doi pubmed - Burke MA, Mutharasan RK, Ardehali H. The sulfonylurea receptor, an atypical ATP-binding cassette protein, and its regulation of the KATP channel. Circ Res. 2008;102(2):164-176.

doi pubmed - Shyng S, Nichols CG. Octameric stoichiometry of the KATP channel complex. J Gen Physiol. 1997;110(6):655-664.

doi pubmed - Matchkov VV. Mechanisms of cellular synchronization in the vascular wall. Mechanisms of vasomotion. Dan Med Bull. 2010;57(10):B4191.

pubmed - Kim DH, Choi JY, Kim SM, Son SM, Choi SY, Koo B, Rah CS, et al. Vasomotion in human arteries and their regulations based on ion channel regulations: 10 years study. J Cell Physiol. 2023;238(9):2076-2089.

doi pubmed - Kim YC. Vasomotion in human arteries and its ion channelbased on regulations: 10 years study. Circulation. Abastract (American Heart Association’s 2024) 2024;150(Supl 1).

- Kim YC, Kim DH, Lee SE, Kim CH, Choi W, Lee SJ, Yun HY. Os 02-06 physiological regulation of vasomotion by intracellular ATP-mediated system in human artery. J Hypertens. 2016;34(Suppl 1-ISH 2016 Abstract Book):e49.

doi pubmed - Hong SH, Sung R, Kim YC, Suzuki H, Choi W, Park YJ, Ji IW, et al. Mechanism of relaxation via TASK-2 channels in uterine circular muscle of mouse. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2013;17(4):359-365.

doi pubmed - Hong SH, Kyeong KS, Kim CH, Kim YC, Choi W, Yoo RY, Kim HS, et al. Regulation of myometrial contraction by ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channel via activation of SUR2B and Kir 6.2 in mouse. J Vet Med Sci. 2016;78(7):1153-1159.

doi pubmed - Kyeong KS, Hong SH, Kim YC, Cho W, Myung SC, Lee MY, You RY, et al. Myometrial relaxation of mice via expression of two pore domain acid sensitive K(+) (TASK-2) channels. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2016;20(5):547-556.

doi pubmed - Park JK, Kim YC, Sim JH, Choi MY, Choi W, Hwang KK, Cho MC, et al. Regulation of membrane excitability by intracellular pH (pHi) changers through Ca2+-activated K+ current (BK channel) in single smooth muscle cells from rabbit basilar artery. Pflugers Arch. 2007;454(2):307-319.

doi pubmed - Sinn DH, Min BH, Ko EJ, Lee JY, Kim JJ, Rhee JC, Kim S, et al. Regional differences of the effects of acetylcholine in the human gastric circular muscle. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010;299(5):G1198-1203.

doi pubmed - Kim SJ, Ahn SC, Kim JK, Kim YC, So I, Kim KW. Changes in intracellular Ca2+ concentration induced by L-type Ca2+ channel current in guinea pig gastric myocytes. Am J Physiol. 1997;273(6):C1947-1956.

doi pubmed - Benham CD, Bolton TB, Lang RJ. Acetylcholine activates an inward current in single mammalian smooth muscle cells. Nature. 1985;316(6026):345-347.

doi pubmed - Sato K, Sanders KM, Gerthoffer WT, Publicover NG. Sources of calcium utilized in cholinergic responses in canine colonic smooth muscle. Am J Physiol. 1994;267(6 Pt 1):C1666-1673.

doi pubmed - Koh SD, Dick GM, Sanders KM. Small-conductance Ca(2+)-dependent K+ channels activated by ATP in murine colonic smooth muscle. Am J Physiol. 1997;273(6):C2010-2021.

doi pubmed - Edwards G, Weston AH. Potassium channel openers and vascular smooth muscle relaxation. Pharmacol Ther. 1990;48(2):237-258.

doi pubmed - Standen NB, Quayle JM. K+ channel modulation in arterial smooth muscle. Acta Physiol Scand. 1998;164(4):549-557.

doi pubmed - Aalkjaer C, Boedtkjer D, Matchkov V. Vasomotion - what is currently thought? Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2011;202(3):253-269.

doi pubmed - Aalkjaer C, Nilsson H. Vasomotion: cellular background for the oscillator and for the synchronization of smooth muscle cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;144(5):605-616.

doi pubmed - Szeto V, Chen NH, Sun HS, Feng ZP. The role of K(ATP) channels in cerebral ischemic stroke and diabetes. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2018;39(5):683-694.

doi pubmed - Nichols CG. ATP-sensitive potassium currents in heart disease and cardioprotection. Card Electrophysiol Clin. 2016;8(2):323-335.

- Sun HS, Feng ZP. Neuroprotective role of ATP-sensitive potassium channels in cerebral ischemia. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2013;34(1):24-32.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Gastroenterology Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.