| Gastroenterology Research, ISSN 1918-2805 print, 1918-2813 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, Gastroenterol Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://gr.elmerpub.com |

Opinion

Volume 18, Number 5, October 2025, pages 239-246

Alcoholic Cirrhosis in the Hispanic Population of the United States: A Retrospective Analysis

Samyak Dhruva, g, Kuldeepsinh P. Atodariab, Don C. Rockeyc, Aakash Goyald, John Bogere, Mashal Bathejaf, Audrey Fonkame

aDepartment of Internal Medicine, Geisinger Wyoming Valley Medical Center, Wilkes-Barre, PA, USA

bDepartment of Hematology-Oncology, Tower Health, Reading, PA, USA

cDepartment of Gastroenterology, Digestive Disease Research Center, Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC), Charleston, SC, USA

dDepartment of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, University of Kentucky, Bowling Green, KY, USA

eDepartment of Gastroenterology, Geisinger Wyoming Valley Medical Center, Wilkes-Barre, PA, USA

fDepartment of Gastroenterology, Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, AZ, USA

gCorresponding Author: Samyak Dhruv, Department of Internal Medicine, Geisinger Wyoming Valley Medical Center, Wilkes-Barre, PA, USA

Manuscript submitted August 25, 2025, accepted September 6, 2025, published online September 29, 2025

Short title: Alcoholic Cirrhosis in the Hispanic Population

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/gr2067

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: The Hispanic population is the fastest-growing ethnic group in the USA and is projected to comprise 30% of the US population by 2050. Despite socioeconomic disadvantages and often presenting with more severe disease phenotypes, previous studies in chronic diseases have shown that Hispanics experience lower overall inpatient mortality compared with other ethnic groups - a phenomenon known as the “Hispanic Paradox”. In alcoholic liver cirrhosis (ALC), this paradox is particularly evident: Hispanics frequently develop more advanced forms of alcoholic liver cirrhosis, yet survival outcomes are often similar or even superior to those of non-Hispanic populations. This study aims to assess the risk and burden of alcoholic liver cirrhosis in the Hispanic population and to compare the clinical phenotype of ALC with that observed in non-Hispanic populations.

Methods: This retrospective analysis used the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) database (2016 - 2019) to examine adults hospitalized with ALC. Patients with other causes of cirrhosis were excluded. Patients were stratified into Hispanic and non-Hispanic groups. Diagnoses, complications, and comorbidities were captured using the International Classification of Disease, 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes. The primary outcome was inpatient mortality; secondary outcomes included length of stay (LOS) and total hospitalization charges (TOTCHG). Statistical analyses were performed using Chi-square, t-tests, and Mann-Whitney U tests.

Results: Among patients hospitalized with alcoholic cirrhosis (n = 1,002,115), 17% were Hispanic. Hispanic patients were younger (mean age 54 vs. 57 years, P < 0.001), more often male (81% vs. 67%, P < 0.001), and had similar Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) scores. Despite slightly lower inpatient mortality (5.9% vs. 6.8%, P < 0.001), Hispanics experienced higher rates of complications, including esophageal varices (28% vs. 23%), variceal bleeding (10% vs. 7%), acute liver failure (27% vs. 25%), and hepatocellular carcinoma (4% vs. 2%) (P < 0.001 for all). Median TOTCHG was significantly higher ($46,494 vs. $38,881, P < 0.001) in Hispanic patients.

Conclusions: Hispanic patients with alcoholic cirrhosis (ALC) experience a higher burden of cirrhosis-related complications and increased healthcare utilization compared to other ethnic groups yet exhibit lower observed inpatient mortality. These disparities highlight the need for earlier detection, culturally tailored public health interventions, and improved access to preventive and specialty liver care to improve outcomes in this vulnerable population.

Keywords: Portal hypertension; Esophageal varices; Hepatocellular carcinoma; Hepatorenal syndrome; Hispanic paradox

| Introduction | ▴Top |

The Hispanic population is the fastest-growing group in the USA, currently comprising 18.4% of the US population, and by the year 2050 is estimated to be 30% of the US population [1, 2]. Hispanics living in the USA have a socioeconomic status equivalent to African Americans. Generally, the worse socioeconomic status is associated with poor overall health-related outcomes, but surprisingly Hispanic population’s mortality rates are lower than African Americans and are comparable to non-Hispanic Whites (NHW) [3]. These epidemiological characteristics have been referred to as “the Hispanic paradox”. This Hispanic paradox is even true in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis (ALC), as demonstrated by our study, which showed decreased inpatient mortality in Hispanic people compared to other ethnic groups (5.9% vs. 6.8% respectively, P < 0.001) [4]. Despite the overall survival advantage of the Hispanic racial population, this group is at increased risk for ALC-related complications leading to prolonged morbidity and increased healthcare cost and utilization.

Chronic liver disease (CLD) disproportionately affects Hispanic population in the USA, with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) representing the most extensively studied etiology. Epidemiologic data indicate that Hispanics have the highest prevalence of MASLD, affecting up to 58.3% of this population, compared to significantly lower rates in non-Hispanic Whites and African Americans [5]. This predisposition, driven by a combination of genetic, environmental, behavioral, and socioeconomic factors, creates a “double hit” scenario when compounded by additional liver insults such as alcohol use.

Alcoholic liver disease (ALD), though less comprehensively studied in Hispanics, reveals unique and paradoxical patterns. Despite a tendency for heavy-drinking subgroups to consume greater quantities for longer periods [6], Hispanic patients often demonstrate a paradoxical survival advantage in cirrhosis.

Paradoxically, this survival benefit exists despite evidence of a more severe ALD phenotype in Hispanics, including earlier disease onset, higher prevalence of obesity and diabetes, and increased frequency of the PNPLA3 rs738409 risk allele associated with steatosis and fibrosis [7].

These findings underscore an important contradiction: Hispanic patients with alcoholic cirrhosis face an increased disease burden and worsened phenotype yet experience improved survival outcomes compared to other racial groups. The present study aims to statistically validate this observation and to investigate the clinical, genetic, and sociocultural mechanisms underlying this paradox. By doing so, we aim to prevent underestimation of disease severity in Hispanics with alcoholic cirrhosis and improve equity in liver disease management.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

The Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) is an administrative database and part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). It is the largest publicly available all-payer inpatient healthcare database designed to produce regional and national estimates of inpatient utilization, access, cost, quality, and outcomes in the USA. Unweighted, it contains data from more than 7 million hospital stays each year; when weighted, it estimates some 35 million hospitalizations. The data in the NIS are deidentified patient data, and the study is thus exempt from the Institutional Review Board approval. This study was conducted in compliance with all the applicable institutional ethical guidelines for care and welfare.

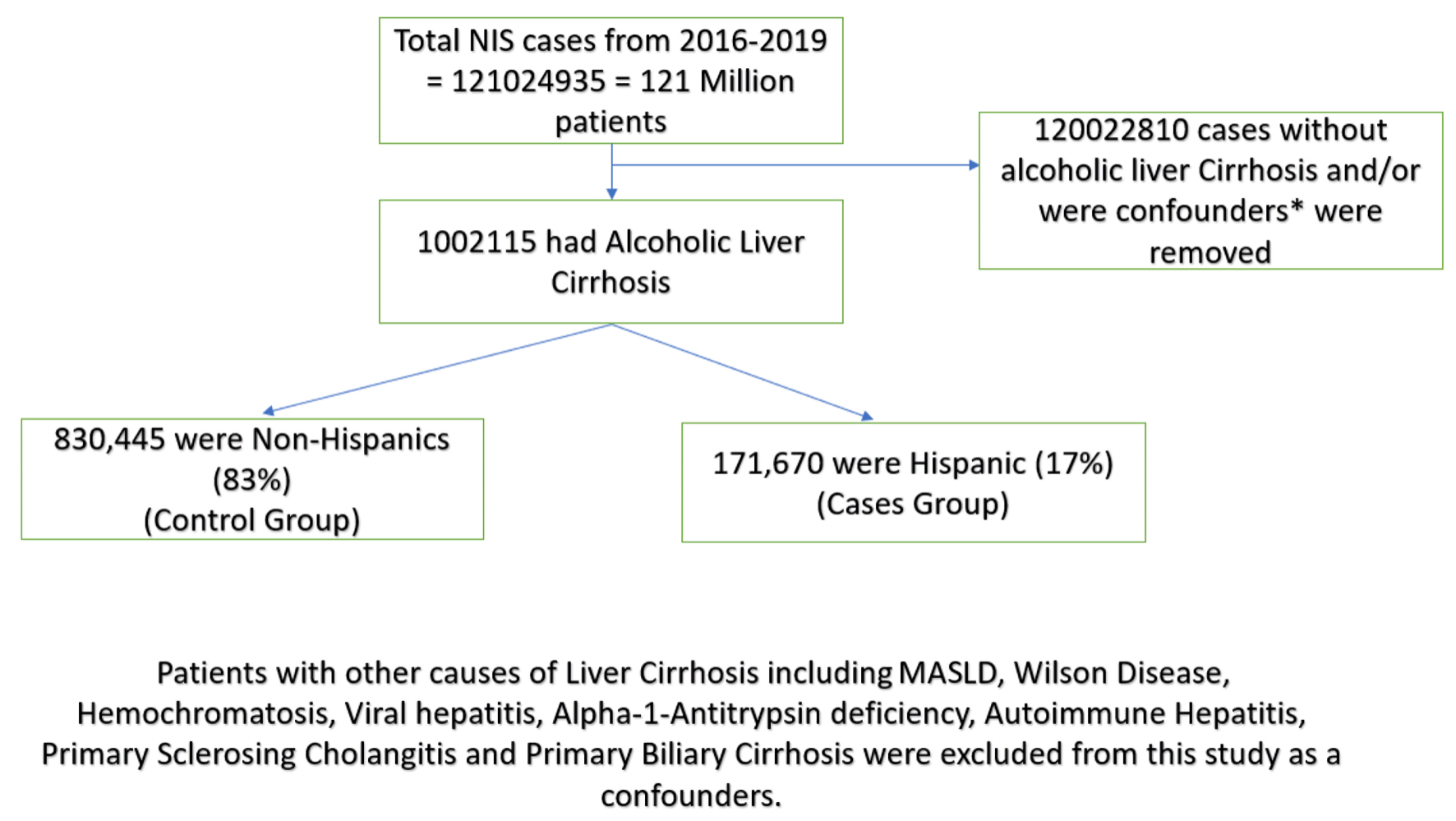

We analyzed approximately 121 million patients from the NIS between 2016 and 2019, including all adult hospitalizations with the International Classification of Disease, 10th Revision (ICD-10) diagnosis code for ALC. From these, hospitalizations that had a diagnosis code related to MASLD, viral hepatitis, Wilson’s disease, hemochromatosis, alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency, primary sclerosing cholangitis and autoimmune hepatitis were excluded to avoid confounding by other causes of liver cirrhosis.

All hospitalizations were stratified into two race-based groups including Hispanics and non-Hispanics (Fig. 1) (White, African American, Asian/Pacific Islander, Native American and others). Furthermore, ICD-10 diagnosis codes were used to identify the presence of comorbidities including diabetes mellitus (DM) (both type 1 and 2 combined), hypertension (HTN) and hyperlipidemia (HLD), as well as complications including ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP), hepatorenal syndrome (HRS), esophageal varices (EV) (both with and without bleeding), hepatic failure (both with and without hepatic encephalopathy), hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), hepatopulmonary syndrome (HPS) and portopulmonary hypertension. ICD-10 procedure codes were used to identify hospitalizations that required transfusion of blood products, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPSS), EV banding and liver transplantation (Supplementary Material 1, gr.elmerpub.com).

Click for large image | Figure 1. CONSORT diagram showing alcoholic cirrhosis in non-Hispanic vs. Hispanic patient population. |

The primary outcome of the study was inpatient death. Secondary outcomes included median hospital length of stay (LOS) and median total hospitalization charges (TOTCHG).

Chi-square tests were utilized to assess the association between qualitative variables. t-tests were utilized to compare mean ages and Charlson comorbidity Index (CCI). Mann-Whitney U tests were utilized to compare median LOS and TOTCHG between Hispanic and non-Hispanic groups.

All the analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 28.0.0.0 (International Business Machines Statistical Package for Social Sciences Version 28.0.0.0, Armonk, NY, USA).

| Results | ▴Top |

Clinical features of the study groups

A total of 1,002,115 patients with ALC were included in the analysis, of whom 17.1% were Hispanics. Hispanic patients were significantly younger than non-Hispanic patients (mean age 54.1 vs. 56.6 years, P < 0.001) and more likely to be male (81.2% vs. 66.9%, P < 0.001). A higher proportion of Hispanic patients were insured through Medicaid (42.0% vs. 28.3%, P < 0.001), whereas non-Hispanics were more frequently covered by Medicare or private insurance (Table 1).

Click to view | Table 1. Demographics |

Most patients were treated at urban teaching hospitals in both groups, but Hispanic patients were less likely to be hospitalized in rural facilities (2.5% vs. 7.9%, P < 0.001). The mean CCI was slightly lower among Hispanics (4.15 vs. 4.26, P < 0.001), though both groups had high comorbidity burdens. Hispanic patients had significantly higher rates of DM (32.9% vs. 23.3%, P < 0.001), but lower prevalence of HTN (48.8% vs. 53.1%, P < 0.001) and HLD (13.5% vs. 16.6%, P < 0.001) (Table 2).

Click to view | Table 2. Comorbidities Among Hispanics and Non-Hispanics |

Primary and secondary outcomes

Despite the increased prevalence of portal hypertensive complications in Hispanic patients compared to non-Hispanic patients, inpatient mortality was lower in Hispanic patients than non-Hispanic patients (6% vs. 7%, P < 0.001) (Table 3). Although the median LOS was similar in both groups (4 days), the median TOTCHG were significantly higher among Hispanic patients than non-Hispanic patients ($46,494 vs. $38,881, P < 0.001). Interestingly, blood product transfusion (including red cell transfusion, platelet transfusion and fresh frozen plasma) was more common in Hispanics (21% vs. 16%, P < 0.001), including red cell transfusions (17% vs. 14%, P < 0.001).

Click to view | Table 3. Primary and Secondary Outcomes/Interventions |

Complications

Portal hypertensive complications were more frequent among Hispanic than non-Hispanic patients (Table 4). This appeared to be most prominent for complications related to varices, with EV being reported in 28% of Hispanic patients, compared to 23% of non-Hispanic patients (P < 0.001), and variceal bleeding occurring in 10% vs. 7% of patients, respectively (P < 0.001). Esophageal variceal banding was performed in 7% of Hispanic patients compared to 5% of non-Hispanic patients (P < 0.001). Ascites was slightly less common in Hispanic patients (48% vs. 51%, P < 0.001), while SBP was slightly more frequent (5% vs. 4%, P < 0.001). Acute liver failure was slightly more frequent in Hispanics, and hepatic encephalopathy was similar in the two groups. Notably, HCC was significantly more common in Hispanics (4% vs. 2%, P < 0.001). Liver transplantation was slightly less frequent among Hispanics (0.6% vs. 0.7%, P < 0.001).

Click to view | Table 4. Portal Hypertensive Complications |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Our study demonstrates that the “Hispanic paradox” - defined as lower overall mortality rates despite lower socioeconomic status and often more severe disease phenotype - prevails even among patients with alcoholic cirrhosis. This phenomenon may be partially explained by the younger age at presentation and a slightly lower yet statistically significant CCI observed in the Hispanic population compared to non-Hispanics, as mentioned above in our study. Additionally, the paradox may be influenced by the classical “salmon bias” hypothesis, which suggests that some Hispanic immigrants return to their country of origin when seriously ill or near death. This practice can lead to underreporting of inpatient deaths and their exclusion from US mortality data, contributing to the observed survival advantage [8, 9].

Here we also show that Hispanic population is disproportionately affected by alcoholic cirrhosis complications, especially Hispanic men. MASLD remains the most common liver disease in Hispanic population followed by ALD and the hepatitis B and C [10]. Several factors contribute to the higher prevalence of alcoholic cirrhosis complications in the Hispanic population. First, it is already proven from the previous studies that Hispanic population in the USA have the highest prevalence of the MASLD (58.3%), followed by Caucasian (44.4%) and African American (35.1%) population [11]. This is likely attributed to the higher prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in the Hispanics compared to NHW and African American populations (31.9%, 23.8% and 21.6% respectively) [12]. Hispanics living in the USA also have the highest intraperitoneal fat and hepatic fat content when compared to other ethnic groups [13].

Histologic and serologic characteristics have also been very different in Hispanics compared with other ethnic groups. Hispanics more frequently had Mallory bodies, more pronounced hepatocyte ballooning, and advanced fibrosis compared with NHW and African American populations [14].

Environmental and behavioral factors do contribute to the above-mentioned ethnic differences observed in CLD patterns, though recent studies have also identified genetic factors that contribute to the worsening outcomes and increased prevalence of CLD in Hispanic population. Recent study has identified a novel polymorphism in a specific allele (rs738409 G) that encodes for the enzyme patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3 (PNPLA3), which is strongly linked to hepatic fat content. Hispanic population have the highest frequency of this polymorphism (49%) followed by NHW (23%) and African American (17%) population [6]. This likely pre-existing MASLD increases susceptibility of Hispanics to alcohol, and they are far more likely to develop alcoholic cirrhosis than other groups.

Behavioral patterns of alcohol drinking also differ significantly between Hispanics and other populations. Hispanics have a lower rate of alcohol consumption than NHW persons; however, among heavy drinkers, Hispanics consume higher amounts than NHW population [15]. Mexican American and Puerto Rican are the Hispanic subgroups with highest documented alcohol consumption. Hospital discharge data have shown that Hispanics have lower prevalence of acute alcoholic hepatitis compared to other ethnic groups though paradoxically they have higher prevalence of the chronic ALD [16]. There are several possible explanations for that. Among current alcohol drinkers, Hispanics experience a two-fold increase in aspartate aminotransferase and gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase compared with NHW persons, suggesting Hispanics alcohol drinkers have higher susceptibility of liver injury [17]. Another possibility is that the PNPLA3 gene, which is higher in prevalence in Hispanic community and has been linked to an increased incidence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, has also recently been shown to be significantly associated with ALD and cirrhosis [7]. Additionally, Hispanics diagnosed with ALD and alcoholic cirrhosis, because of their same genetic makeup regarding PNPLA3, are also susceptible to MASLD, and many have undiagnosed components of MASLD. Together with heavy alcohol abuse, this makes them disproportionately susceptible to alcohol-associated liver injury. Our study is the first to highlight that “Hispanic men” are at higher risk of alcoholic cirrhosis-related complications. It can be attributed to environmental, behavioral and genetic factors. Genetic studies of PNPLA3 to identify whether Hispanic men have more chances to carry this gene may provide the answer. Also, behavioral factors contribute significantly; within Hispanic culture, men drink more often than female, which may contribute to this finding.

Hispanic cirrhotic men have more risk of EV, hepatic encephalopathy and HCC. There are several reasons why Hispanics are disproportionately affected by the EV. First, the Hispanic population is at higher risk of de novo development of EV [18]. Tavakoli et al showed that Hispanics were 54% less likely than non-Hispanic Whites to undergo EV screening within the first year after the diagnosis of liver cirrhosis [19]. Another study comparing the several causes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) in different ethnicities found that the most common cause of the UGIB in the Hispanic population was EV [20]. Studies have also shown that the Hispanic population was the most non-complaint with the EV ligation protocol, and the risk of re-bleeding was highest in the non-English speaking patients, especially Hispanics [21]. The previous mentioned studies have been relatively old, though our study using NIS database (2016 - 2019) has shown that not only Hispanic community is at higher risk of all EV (P < 0.001), but they are also at the highest risk of bleeding EV. This is also consistent with our study’s findings that Hispanics required the highest amount of blood product transfusion, and also red cell transfusion (P < 0.001). Our study, using the latest database, along with previous studies, has proven that the Hispanic community disproportionately develops EV. Combined with poor screening attitudes, this results in Hispanic community to be affected the most - not only by the varices but also by bleeding EV, which requires significant amount of transfusion efforts and poor overall outcomes. There needs to be a strong effort to raise the awareness of screening concept in the Hispanic community, which will require breaking down several socioeconomic, language and cultural barriers, especially in Hispanic men.

Hispanic community also is at higher risk of HCC compared to non-Hispanics per our study (3.6% vs. 1.9%, P < 0.001). HCC is the most common liver malignancy with more than half a million new cases diagnosed annually [22, 23]. Hispanic population per our study is significantly more at risk of HCC especially in alcoholic cirrhosis population. Since it is the second largest population group in the USA, it is likely that the increasing incidence trend of HCC and mortality trend with HCC correlate with the same trends of ALD and cirrhosis seen in Hispanic population. Hispanic individual tends be diagnosed with HCC in the later stages due to poor screening efforts. Previous studies have shown that Hispanic patients with liver cirrhosis were less likely to undergo screening for HCC 2 years before the diagnosis of HCC compared to non-Hispanics [24]. Not only that, even if diagnosed early, Ha et al reported that 70% of Hispanic population with early and localized HCC receive no treatment [25]. Our study is also consistent with previous studies, which showed that Hispanics are less likely to receive liver transplantation.

Another risk factor apart from poor screening could be high incidence of DM and obesity in Hispanic population. Our study has shown significantly high rates of diabetes in Hispanics vs. non-Hispanics (32.9% vs 23.3%, P < 0.001). Previous studies have proven that people with diabetes have two times higher risks of developing HCC [26]. The Hispanic population with PNPLA3 mutation is more affected by diabetes and subsequently by MASLD. We hypothesize that alcohol abuse causes a “double hit” (alcohol and MASLD together) in the Hispanic population and speeds up the development of the liver cirrhosis and HCC, as it is already affected by the MASLD. According to one study, one in five new HCC diagnoses occurs in the Hispanic community [27]. Despite this huge burden, less than half qualified for liver transplantation per Milan criteria, likely due to poor screening efforts in the Hispanic population as mentioned above likely leading to late diagnosis of the liver cancer in advanced stages. The HCC incidence in Hispanic community surpassed that of Asian population in 2012 - previously the most affected ethnicity - and now making Hispanic community the most affected by HCC burden. While the rising burden of HCC in Hispanic community is concerning, even more concerning are the significant disparities this community faces in access to HCC treatment [28]. In our study, males were significantly more affected by alcoholic cirrhosis and likely HCC, which is consistent with previous studies showing that males are two to four times more likely to develop HCC. Despite all these findings, Hispanics with liver cirrhosis have lower inpatient mortality compared with other ethnic groups, which is also seen in previous studies. Our study also proves the “Hispanic paradox” prevails in patients with ALC [4].

The study has several limitations. It is a retrospective analysis of the NIS database. There are certain patient characteristics which are not available in the database and cannot be studied. The vital signs and laboratory values cannot be compared.

There are several strengths of the studies as well. It is the largest database study since 2000s evaluating alcoholic cirrhosis and complications in the Hispanic community. We have evaluated approximately 121 million patient encounters to draw our conclusions.

Conclusions

The Hispanic population faces a growing public health crisis, driven by the rising prevalence of metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and MASLD, which increase susceptibility to alcohol-induced liver damage on top of pre-existing fatty liver disease. Consequently, they often present with a more severe phenotype of alcoholic cirrhosis, including a higher incidence of EV and HCC, resulting in a significant financial burden on the US healthcare system. Alarmingly, the incidence of HCC in this community continues to rise. Enhanced public health efforts are urgently needed, focusing on HCC prevention and increasing awareness of this heightened vulnerability. Our study underscores the critical role of the gastroenterology community in addressing this emerging epidemic in Hispanic population, improving outcomes for patients with alcoholic cirrhosis, and preventing HCC development. Furthermore, the lower observed mortality in the Hispanic population may be misleading, potentially due to the “salmon bias”, and should not diminish the imperative for targeted public health initiatives in this high-risk group.

| Supplementary Material | ▴Top |

Suppl 1. ICD 10 diagnosis codes and procedure codes used in the study.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

Dr. Rockey was supported by the National Institutes of Health (P30 DK123704 and P20 GM130457).

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Informed Consent

Our study uses deidentified NIS database and does not need patient consent.

Author Contributions

Dr. Samyak Dhruv is the main author who came up with this unique idea. He performed statistical analyses including bivariate and multivariate analysis with logistic regression and made initial manuscript draft. He also revised and finalized the draft for the publication. Dr. Kuldeepsinh P. Atodaria and Dr. Aakash Goyal helped with writing the manuscript. Dr. Audrey Fonkam did the review from a hepatological perspective. Dr. John Boger, the main attending on our paper, provided his valuable expert opinion in creating the study design and helped with statistical analysis and review of the draft. Dr. Mashal Batheja, an expert on our study, provided valuable expert insights in finalizing the manuscript draft. Dr. Don C. Rockey helped with study design, manuscript editing, and finalizing the draft. He is also an expert researcher on our study.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Abbreviations

NIS: Nationwide Inpatient Sample; HCUP: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project; ALC: alcoholic liver cirrhosis; MASLD: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; ICD-10: International Classification of Disease, 10th Revision; SBP: spontaneous bacterial peritonitis; HRS: hepatorenal syndrome; EV: esophageal varices; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; HPS: hepatopulmonary syndrome; TIPSS: transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt; LOS: length of stay; TOTCHG: total hospitalization charges; PNPLA3: patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3; CCI: Charlson Comorbidity Index

| References | ▴Top |

- Carrion AF, Ghanta R, Carrasquillo O, Martin P. Chronic liver disease in the Hispanic population of the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9(10):834-841.

doi pubmed - United, States Census Bureau 2019. ACS demographic and housing estimates. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=United%20States&g=0100000US&tid=ACSDP1Y2019.DP05.

- Hummer RA. Adult mortality differentials among Hispanic subgroups and non-Hispanic whites. Soc Sci Q. 2000;81(1):459-476.

pubmed - Atiemo K, Mazumder NR, Caicedo JC, Ganger D, Gordon E, Montag S, Maddur H, et al. The hispanic paradox in patients with liver cirrhosis: current evidence from a large regional retrospective cohort study. Transplantation. 2019;103(12):2531-2538.

doi pubmed - Gulati R, Moylan CA, Wilder J, Wegermann K. Racial and ethnic disparities in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Metab Target Organ Damage. 2024;4:9.

doi - Chartier K, Caetano R. Ethnicity and health disparities in alcohol research. Alcohol Res Health. 2010;33(1-2):152-160.

pubmed - Tian C, Stokowski RP, Kershenobich D, Ballinger DG, Hinds DA. Variant in PNPLA3 is associated with alcoholic liver disease. Nat Genet. 2010;42(1):21-23.

doi pubmed - Moylan CA, Brady CW, Johnson JL, Smith AD, Tuttle-Newhall JE, Muir AJ. Disparities in liver transplantation before and after introduction of the MELD. JAMA. 2008;300(2):2371-2378.

doi pubmed - Abraido-Lanza AF, Dohrenwend BP, Ng-Mak DS, Turner JB. The Latino mortality paradox: a test of the "salmon bias" and healthy migrant hypotheses. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(10):1543-1548.

doi pubmed - Browning JD, Szczepaniak LS, Dobbins R, Nuremberg P, Horton JD, Cohen JC, Grundy SM, et al. Prevalence of hepatic steatosis in an urban population in the United States: impact of ethnicity. Hepatology. 2004;40(6):1387-1395.

doi pubmed - Williams CD, Stengel J, Asike MI, Torres DM, Shaw J, Contreras M, Landt CL, et al. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis among a largely middle-aged population utilizing ultrasound and liver biopsy: a prospective study. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(1):124-131.

doi pubmed - Ford ES, Giles WH, Dietz WH. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among US adults: findings from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. JAMA. 2002;287(3):356-359.

doi pubmed - Guerrero R, Vega GL, Grundy SM, Browning JD. Ethnic differences in hepatic steatosis: an insulin resistance paradox? Hepatology. 2009;49(3):791-801.

doi pubmed - Mohanty SR, Troy TN, Huo D, O'Brien BL, Jensen DM, Hart J. Influence of ethnicity on histological differences in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2009;50(4):797-804.

doi pubmed - Alcoholism N-NIoAAa. Alcohol and hispanic community. Accessed Jan 22, 2022. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/alcohol-and-hispanic-community.

- Yang AL, Vadhavkar S, Singh G, Omary MB. Epidemiology of alcohol-related liver and pancreatic disease in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(6):649-656.

doi pubmed - Stewart SH. Racial and ethnic differences in alcohol-associated aspartate aminotransferase and gamma-glutamyltransferase elevation. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(19):2236-2239.

doi pubmed - Fontana RJ, Sanyal AJ, Ghany MG, Lee WM, Reid AE, Naishadham D, Everson GT, et al. Factors that determine the development and progression of gastroesophageal varices in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(7):2321-2331.e2.

doi pubmed - Tavakoli H, Robinson A, Liu B, Bhuket T, Cheung R, Wong R. Race/ethnicity-specific disparities in the receipt of screening for esophageal varices among patients with cirrhosis: 891. Official Journal of the American College of Gastroenterology | ACG. 2016;111:S389.

- Wollenman CS, Chason R, Reisch JS, Rockey DC. Impact of ethnicity in upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48(4):343-350.

doi pubmed - Chandrasekhara V, Yepuri J, Sreenarasimhaiah J. Clinical predictors for recurrence of esophageal varices after obliteration by Endoscopic Band ligation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:148.

- Mittal S, El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma: consider the population. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47(Suppl 0):S2-6.

doi pubmed - Altekruse SF, McGlynn KA, Reichman ME. Hepatocellular carcinoma incidence, mortality, and survival trends in the United States from 1975 to 2005. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(9):1485-1491.

doi pubmed - Pomenti S, Gandle C, Abu Sbeih H, Phipps M, Livanos A, Guo A, Yeh J, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in hispanic patients: trends and outcomes in a large United States cohort. Hepatol Commun. 2020;4(11):1708-1716.

doi pubmed - Ha J, Yan M, Aguilar M, Tana M, Liu B, Frenette CT, Bhuket T, et al. Race/ethnicity-specific disparities in hepatocellular carcinoma stage at diagnosis and its impact on receipt of curative therapies. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50(5):423-430.

doi pubmed - El-Serag HB, Tran T, Everhart JE. Diabetes increases the risk of chronic liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2004;126(2):460-468.

doi pubmed - Robinson A, Ohri A, Liu B, Bhuket T, Wong RJ. One in five hepatocellular carcinoma patients in the United States are Hispanic while less than 40% were eligible for liver transplantation. World J Hepatol. 2018;10(12):956-965.

doi pubmed - Wong RJ, Devaki P, Nguyen L, Cheung R, Nguyen MH. Ethnic disparities and liver transplantation rates in hepatocellular carcinoma patients in the recent era: results from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registry. Liver Transpl. 2014;20(5):528-535.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Gastroenterology Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.