| Gastroenterology Research, ISSN 1918-2805 print, 1918-2813 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, Gastroenterol Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://gr.elmerpub.com |

Original Article

Volume 000, Number 000, January 2026, pages 000-000

Clinical Efficacy of Early and Late Vedolizumab or Infliximab Interventions in Moderate Ulcerative Colitis: A Multicenter, Retrospective Cohort Study

Rui Ping Menga, b, Jian Zhangc, Hao Qi Weia, g, Xi Ping Liaoa, En Liua, Hui Lina, Bao Bao Huanga, Lin Lyud, Yan Ling Weie, Jian Yun Zhouf, h, Xia Xiea, h

aDepartment of Gastroenterology, the Second Affiliated Hospital of the Army Medical University, Chongqing 400037, China

bDepartment of Cardiology, Fuwai Yunnan Cardiovascular Hospital, Yunnan 650032, China

cCenter of Teaching and Training, DaPing Hospital of Army Medical University, Chongqing 400042, China

dDepartment of Gastroenterology, the Second Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing 400060, China

eDepartment of Gastroenterology, DaPing Hospital of Army Medical University, Chongqing 400042, China

fClinical Medical Research Center, the Second Affiliated Hospital of the Army Medical University, Chongqing 400037, China

gDepartment of Gastroenterology, the PLA 77th Group Army Hospital, Sichuan 614000, China

hCorresponding Authors: Xia Xie, Department of Gastroenterology, the Second Affiliated Hospital of the Army Medical University, Chongqing 400037, China; Jian Yun Zhou, Clinical Medical Research Center, the Second Affiliated Hospital of the Army Medical University, Chongqing 400037, China

Manuscript submitted September 29, 2025, accepted December 2, 2025, published online January 4, 2026

Short title: Early vs. Late VDZ/IFX for Moderate UC

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/gr2092

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Late biologic intervention has been partly displaced during the last decade by early biologic therapy. However, there is a scarcity of direct evidence to inform clinical decision-making with greater confidence. The study aimed to compare the efficacy and safety of the early biologic approach with those of the late biologic approach in patients with moderate ulcerative colitis (UC).

Methods: Moderate UC patients treated with biologics between January 2021 and February 2024 from three Chinese centers were retrospectively included. The outcomes included steroid-free clinical remission rates, clinical remission rates, and mucosal healing rates at week 14 and week 52.

Results: A total of 124 moderate UC cases were included. No marked differences in the steroid-free clinical remission rates and clinical remission rates were observed between the two groups at week 14 or at week 52 (P > 0.050). The early biologic therapy group exhibited a numerically higher mucosal healing rate at week 14 (23.3% vs. 12.5%, P = 0.115) and week 52 (15/27 (55.6%) vs. 13/37 (35.1%), P = 0.104) compared to the late biologic therapy group, yet there was no significant difference between two groups.

Conclusion: No significant differences in steroid-free clinical remission, clinical remission, and mucosal healing were observed between early and late biologic intervention group.

Keywords: Early biologic intervention; Late biologic intervention; Moderate ulcerative colitis; Efficacy

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a recurrent inflammatory disease characterized by progressive mucosal inflammation that initiates in the rectum and potentially extends to proximal colon segments [1]. The prominent clinical symptoms are persistent or recurrent bloody diarrhea, abdominal discomfort, urgency, and tenesmus, sometimes accompanied by peripheral arthritis, oral ulcers, erythema nodosum, iritis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, and other extraintestinal manifestations [2, 3].

Traditional UC therapeutic regimens include 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA), corticosteroids, and immunomodulators. The advent of biologic agents that can facilitate specific immune modulation has broadened the therapeutic horizon for patients with varied drug history profiles. Nevertheless, biologics are often reserved for cases in which UC patients have high risk factors or exhibit traditional therapy ineffectiveness or intolerance [4, 5]. In such a situation, late biologic intervention may amplify complications, hospitalizations, and colectomies and deteriorate quality of life. Moreover, this approach potentially leads to excess corticosteroid consumption, thereby increasing the risk of side effects, such as osteoporosis, obesity, and elevated blood sugar, and approximately 50% of patients receiving steroids experience side effects [6, 7]. Moreover, increasing evidence shows that UC should be considered a disease with a progressive nature associated with adverse consequences such as Crohn’s disease (CD), so it is reasonable to treat UC early to alter the disease course and prevent complications [8-12]. In the meantime, evidence suggests that there is an expanding tendency to prescribe biologics for patients with UC, as manifested by the early intervention with biologics in patients’ disease course [13]. However, although the strategy of early intervention has accumulating evidence in CD, there is less evidence supporting its impact on UC [10, 13], especially in those with moderate UC.

Therefore, we urgently need a large amount of evidence to verify whether early intervention with biologics can achieve a better prognosis than late. The current multicenter, retrospective cohort study was performed to compare the efficacy and safety of early intervention with biologics with those of late biologic initiation in moderate UC patients.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

Study design and patients

We carried out a multicenter, retrospective observational study at three Chinese hospitals in Southwest China between January 2021 and February 2024. The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) age ≥ 18 years; 2) diagnosis of moderate UC (total Mayo score ranging from 6 to 10 at baseline); 3) treatment with vedolizumab (VDZ) or infliximab (IFX) for at least 14 weeks; and 4) patients who have not received any biological agents. The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) had a history of colectomy and 2) were pregnant.

The pharmacotherapy regimen was as follows: three 300 mg infusions of VDZ were prescribed at weeks 0, 2, and 6, with subsequent infusions of the same dosage every 8 weeks. IFX was started by intravenous infusion of 5 to 10 mg/kg at weeks 0, 2, and 6, followed by the analogous dose every 8 weeks.

Data collection

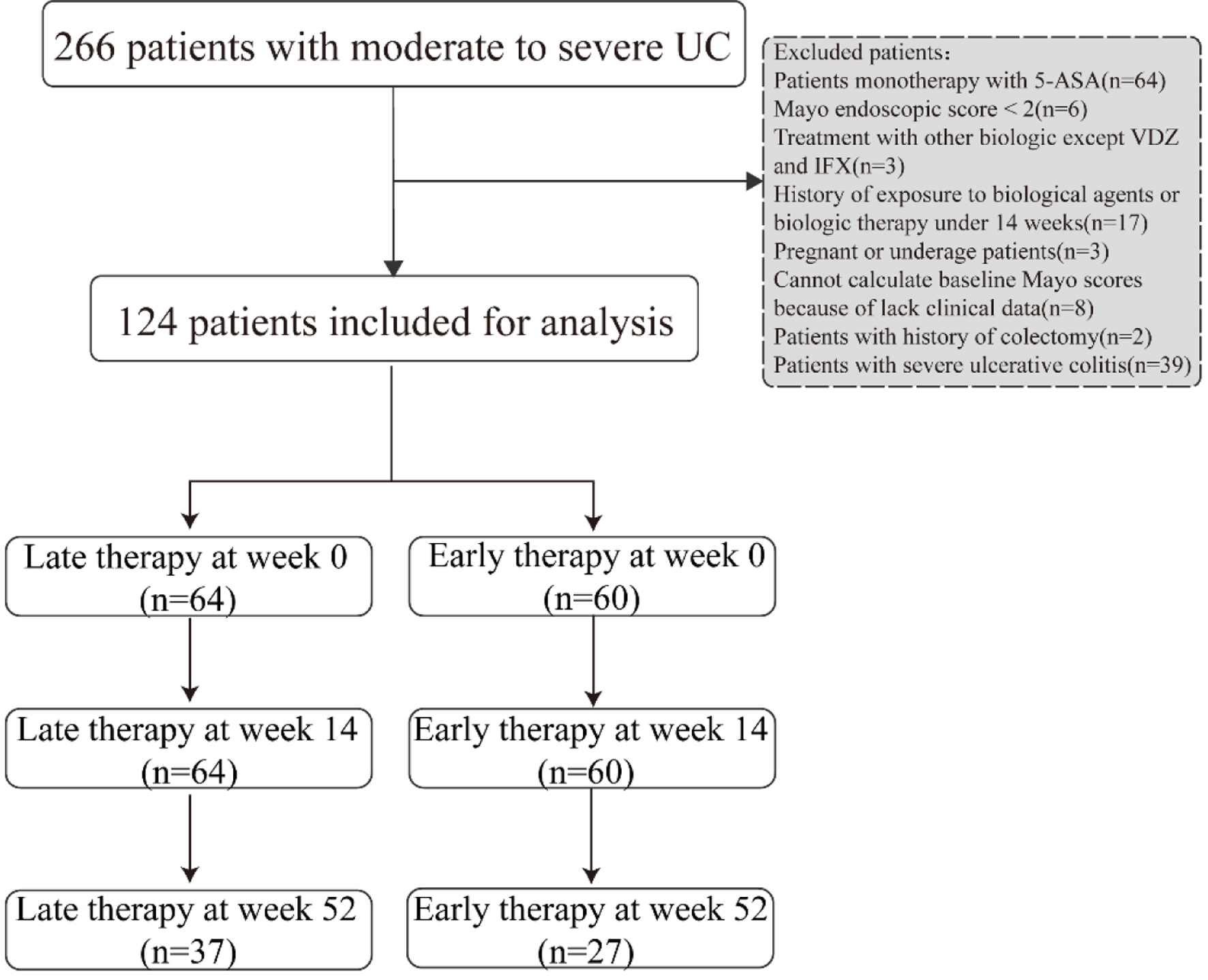

Patients were divided into late intervention group and early intervention therapy group according to the therapeutic strategy (Fig. 1). The following data at inclusion were collected through a standardized form: 1) basic information: age, sex, body mass index (BMI), smoking history, disease duration, and disease extent according to the Montreal classification [14]; 2) medical history: 5-ASA, hormone or immunosuppressive; 3) clinical characteristics: clinical symptoms, Mayo endoscopic scores, Mayo scores, and disease severity according to Mayo scores [15]; 4) inflammatory and nutritional indicators: hypersensitive C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), platelet (PLT), hemoglobin (Hb), albumin (ALB) levels, etc.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Study flowchart of patients included in analysis. |

Follow-up

The follow-up period began with the initial use of biologics until death, colectomy, discontinuation of treatment, or the end of the follow-up period in May 2024. During the follow-up period, the following information was collected at each treatment administration: dose and frequency of biologics, concomitant therapy drugs, clinical symptoms, biological variables (hs-CRP, ESR, PLT, Hb, and ALB levels), and available endoscopic data. Treatment optimization, adverse events (infusion reactions, concomitant infections, immune system diseases, tumors, colectomy, death, etc.), and the reasons for treatment discontinuation were also recorded during the follow-up period.

Objectives and definitions

The outcome evaluation indices included: 1) the steroid-free clinical remission rates, clinical remission rates, and mucosal healing rates at 14 and 52 weeks; 2) the Mayo score, inflammatory indices, and nutritional indices at 14 weeks; 3) the time to achieve clinical remission; and 4) adverse events. Steroid-free clinical remission was defined by a partial Mayo score (stool frequency plus blood in stool) < 2 and no use of any form of hormone for at least 4 weeks [16, 17]. Clinical remission was defined by a normal stool frequency and a bleeding subscore of 0 [18]. Mucosal healing was defined by a Mayo endoscopic score of 0 [18].

Early biologic treatment was defined as disease duration ≤ 36 months (determined by time since diagnosis, not symptom onset) and no prior or current treatment with disease-modifying drugs (e.g., steroids, immunomodulators or biologics). Conversely, late biologic therapy was defined by disease duration > 36 months or exposure to steroids or immunomodulators before first biological treatment [19].

Treatment optimization included increasing the infusion frequency or dose of biologics [20].

Statistical analysis

Data analyses were performed using SPSS 25.0. Since there was only a small amount of missing data for BMI, ESR, PLT, and ALB (< 5%), we used the method of multiple interpolation to address the missing values. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to test whether the continuous variables conformed to a normal distribution. Variables that conformed to a normal distribution are reported herein as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) and were analyzed using Student’s t-test; otherwise, variables were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test and are reported as medians (interquartile ranges). Categorical data are presented as percentages and were analyzed using the Chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test. All analyses used two-sided statistical tests. P < 0.05 was considered the threshold for significance.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated to demonstrate the clinical remission rates for each treatment strategy over time, and significant differences were compared with the log-rank test.

Ethical statements

This study was conducted with respect to the requirements set out in the applicable standard operation procedures of the Medical Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Medical University (2023-Research No. 080-01).

| Results | ▴Top |

Baseline characteristics

Our study cohort included 124 patients with moderate UC. The mean age of the enrolled patients was 43.8 years, 63.7% were men, and the mean disease duration was 56.3 months. With respect to disease extent, 47 (37.9%) had left-sided disease, and 77 (62.1%) had pancolitis. The subjects were divided into a late biologic treatment group (n = 64) and an early biologic therapy group (n = 60) according to the therapeutic strategy that they received. There was no significant difference in baseline parameters between the late initiation group and early intervention group (Table 1).

Click to view | Table 1. Population Characteristics at Baseline Stratified by Treatment Strategy |

Effectiveness evaluation at week 14

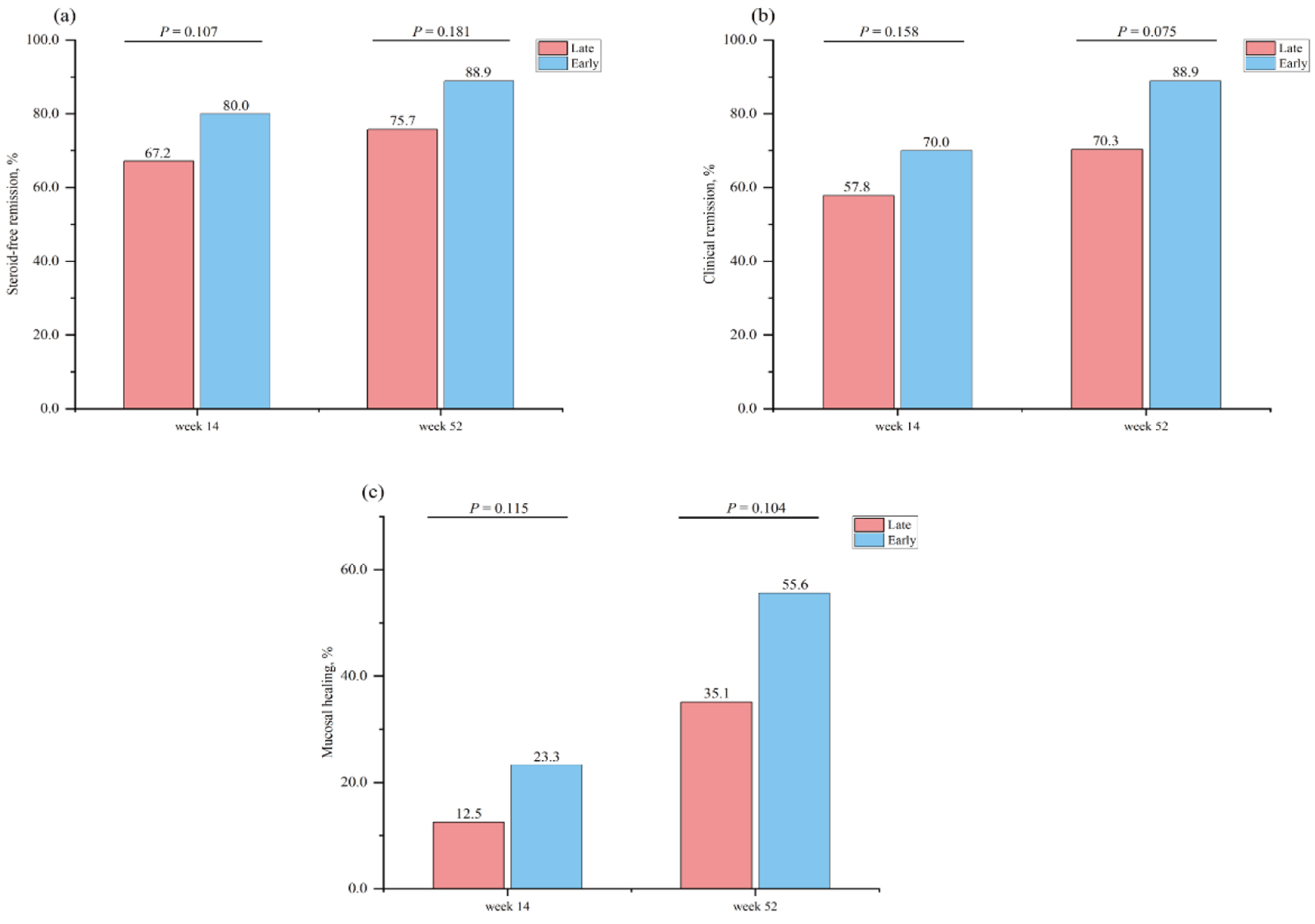

Steroid-free clinical remission at week 14 was achieved in 43/64 (67.2%) in the early biologic intervention group versus 48/60 (80.0%) in the late biologic initiation group (P = 0.107). The corresponding rates of clinical remission were 37/64 (57.8%) and 42/60 (70.0%), respectively (P = 0.158). In the early biologic treatment group, 14/60 (23.3%) patients had mucosal healing versus 8/64 (12.5%) in the late biologic therapy group (P = 0.115) (Fig. 2).

Click for large image | Figure 2. Proportion of patients in steroid-free remission at week 14 and week 52 stratified by therapeutic strategy (a). Proportion of patients in clinical remission at week 14 and week 52 stratified by therapeutic strategy (b). Proportion of patients in mucosal healing at week 14 and week 52 stratified by therapeutic strategy (c). |

With respect to treatment optimization before week 14, the proportion of patients who experienced treatment optimization was similar between the late therapy group and the early therapy group (4.7% (3/64) vs. 5.0% (3/60), P > 0.999). Among the three patients who received late biologic treatment, two patients received an additional biologic infusion at week 10, and one patient received an additional biologic infusion at week 1. Among the three patients who received early biologic treatment, two patients increased their infusion dosage from week 1 and week 10 and one patient received an increased infusion dosage beginning at week 6.

Additionally, we found that the Mayo score, nutritional metrics, and inflammatory indices did not significantly differ (P > 0.05) (Table 2).

Click to view | Table 2. Mayo score, inflammatory index and nutritive index at week 14. |

Effectiveness evaluation at week 52

In total, 51.6% of patients (64/124) completed 52 weeks of follow-up in the cohort (Table 3). The mean follow-up duration of the enrolled patients was 37.9 weeks. The proportion of patients treated with the early biologic strategy who achieved clinical remission at week 52 was greater than that of the late biologic therapy patients, but this difference was not significant (26/37 (70.3%) vs. 24/27 (88.9%), P = 0.075). A similar picture was observed for steroid-free clinical remission and mucosal healing, which was numerically greater for early biologic therapy than for late biologic therapy but also did not significantly differ (28/37 (75.7%) vs. 24/27 (88.9%), P = 0.181) (13/37 (35.1%) vs. 15/27 (55.6%), P = 0.104) (Fig. 2).

Click to view | Table 3. Assessment at Follow-Up Endpoint |

We found that the ESR level of the early biologic therapy group after 52 weeks of treatment was significantly lower than that of the late biologic therapy group (13.0 vs. 6.0 mm/h, P = 0.021). However, the Mayo score, nutritional metrics, and other inflammatory indices did not significantly differ (P > 0.05) (Table 4).

Click to view | Table 4. Mayo Score, Inflammatory Index, and Nutritive Index at Week 52 |

These frequencies did not differ significantly from the frequency seen in patients who experienced treatment optimization between the late biological management group and the early biologic treatment group (5.4% (2/37) vs. 7.4% (2/27), P > 0.999). Among the two patients who received early biologic treatment, one patient increased their infusion dosage from week 18 and week 24 and one patient received an increased infusion dosage beginning at week 38. Two patients increased their infusion dosage from week 22 in the late biologic therapy group.

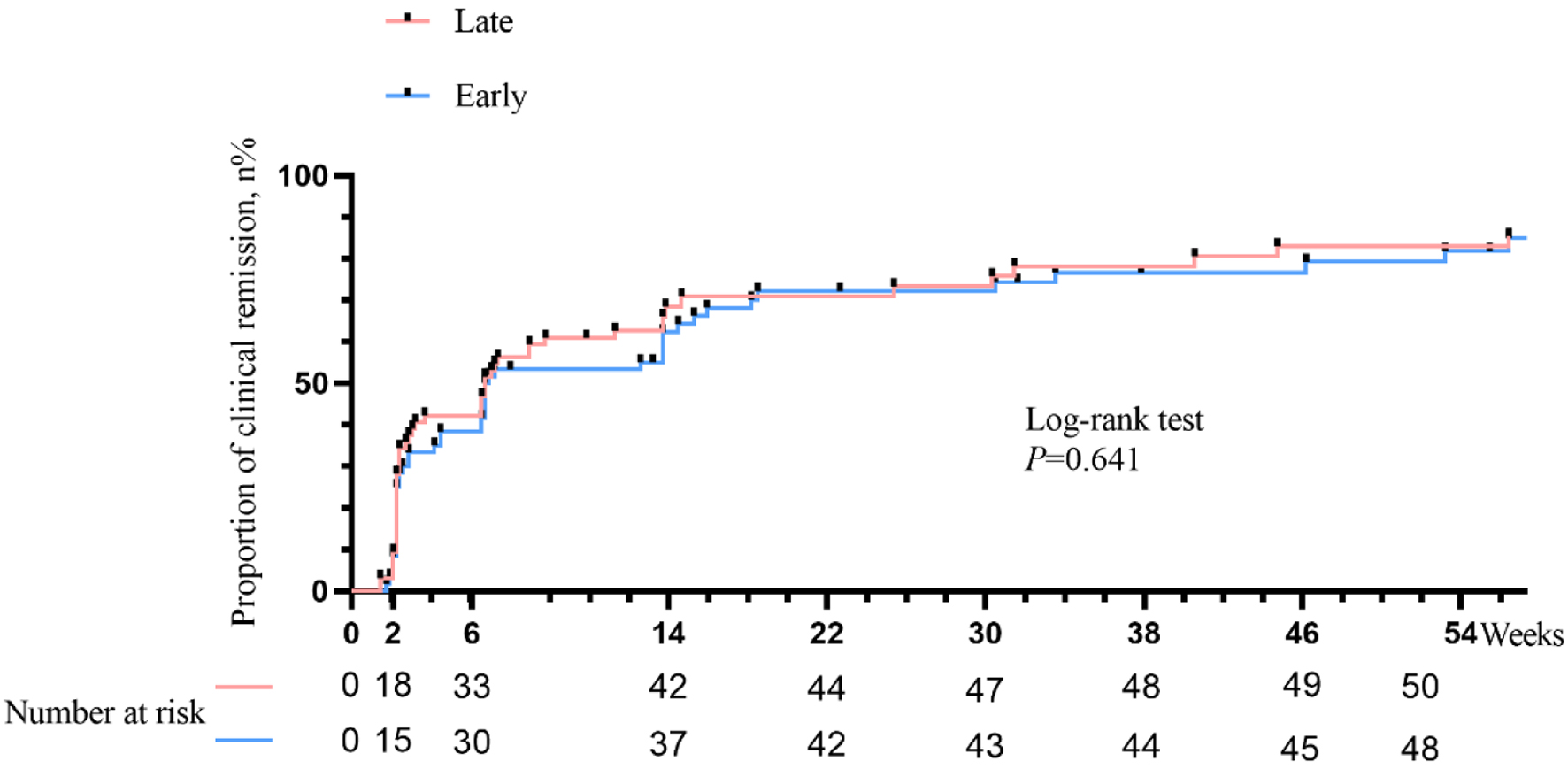

Kaplan-Meier curve of clinical remission

The time to achieve clinical remission in late biologic therapy versus early biologic management during the follow-up period is shown in Figure 3. There was not a significant difference in the time to reach clinical remission in favor of early biologic treatment. The median time for achieving clinical remission with both therapies was 42 days (P = 0.641).

Click for large image | Figure 3. Kaplan-Meier curves of time to clinical remission stratified by therapeutic strategy. |

Safety data

In total, there were 4.7% (3/64) documented adverse events in the late biologic therapy group (one Clostridium difficile infection and two allergic reaction) and 8.3% (5/60) in the early intervention group (three allergic reactions, one viral pneumonia, and one abnormal liver function); these differences were not significant (P = 0.645). Moreover, during the follow-up period, one patient in the late biologic management group underwent colectomy intervention, but none for the early biologic therapy group (1.6% (1/64) vs. 0.0% (0/60), P > 0.999).

| Discussion | ▴Top |

The guideline has recommended that for patients with moderate to severe UC, early intervention with biologics is more preferable [21]. Therefore, we would like to conduct this study to explore whether this advantage is more pronounced in patients with moderate UC. To date, there is no specific guidance on how best to define early biologic intervention in UC or early UC [10, 12].

In our study, early intervention with biologics was defined as disease duration shorter than 3 years and the upfront use of biologics in patients with moderate UC, and patients in the late biologic treatment group had a disease duration greater than 3 years or had been exposed to steroids or immunomodulators before initiation of biological therapy. There were no statistically significant differences in the rates of steroid-free clinical remission, clinical remission, and mucosal healing at both weeks 14 and 52 between two groups.

Similarly, more studies have defined early intervention with biologics based on disease duration, and these studies indicate that early intervention has a negligible impact on UC [12, 19, 22-26]. For example, previous research by Faleck et al demonstrated no significant divergence in remission rates at 6 months between UC patients treated with VDZ who exhibited a disease duration of ≤ 2 years versus those with a longer disease duration [24]. Consistent with the conclusions of previous studies, after sensitivity analysis, even if the threshold is set at 2 years, there is still no statistical difference (Supplementary Material 1, gr.elmerpub.com). Similarly, another retrospective study revealed no notable differences in clinical and colectomy outcomes between early and late initiators of anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) therapy within the first 3 years after diagnosis [25]. Furthermore, subanalysis of the ACT 1 and ACT 2 trials could not discern any difference in response rates to IFX in patients with disease durations less than or more than 3 years [23]. Unlike CD, the cutoff value employed has no influence on the duration of UC disease or on the efficacy of biological agents, regardless of the threshold used. Meanwhile, previous studies have also found that UC patients receiving anti-TNF or VDZ therapy had similar clinical outcomes to those of late initiators [24, 26, 27].

Mucosal healing is a crucial therapeutic goal in UC [9, 28, 29], and is associated with long-term clinical remission, lower incidences of clinical relapse, the need for hospitalization and surgery, and reduced rates of dysplasia and colorectal cancer. In achieving mucosal healing, biologics were rated significantly better than all other classes (P < 0.05) [5]. Thus, theoretically, earlier use of biologics could lead to mucosal healing and have a long-term benefit. According to our study, we observed that although this difference was not significant, there were numerically higher mucosal healing rates at week 14 and week 52 for early intervention than for late treatment. The reason for this difference might be that patients starting early biologic therapy for UC are more likely to have severe disease. Indeed, we observed substantial differences in serologic inflammatory disease severity between early and late initiators of biologic therapy.

In addition to efficacy, the safety profile should also be considered. In our study, early intervention with biologic and conventional step-up management had similar proportions of adverse events and colectomy. However, the result should be interpreted with caution because the long-term safety beyond 52 weeks was unknown, and some patients in our study did not reach the end of follow-up.

Despite our findings, it is essential to recognize several limitations of our study. First, although there are no statistic differences in Mayo score, inflammatory index and nutritive index at week 14 and 52, a lack of fecal calprotectin data, which is a useful surrogate marker of gastrointestinal inflammation, restricted our analysis. Second, the follow-up period of some patients was less than 52 weeks, which may have caused a certain bias in the efficacy and safety evaluation over the 52-week period. Last, given the retrospective nature of our data collection, there is an inherent need for prospective trials to more robustly determine the efficacy and safety of early intervention.

In conclusion, our multicenter, retrospective cohort study found that patients starting early biologic therapy within 3 years of UC diagnosis had similar rates of steroid-free clinical remission, clinical remission, mucosal healing, and the risk of adverse events compared to late initiators in moderate UC patients.

| Supplementary Material | ▴Top |

Suppl 1. Clinical efficacy of early and late biologic intervention at week 14 and week 52.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the participants and all the researchers who participated in this study.

Financial Disclosure

This work was supported by the Chongqing Young and Middle-aged Medical Talents Project (YXGD202401) and the Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing Science and Technology Bureau Project (CSTB2023NSCQ-ZDX0007).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest with respect to the research.

Informed Consent

The study was observational and no consent to participate was required.

Author Contributions

Study concept and design; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; study supervision: Xia Xie and Jian Yun Zhou. Acquisition of data and critical revision of the manuscript: Yan Ling Wei and Lin Lyu. Statistical analysis; drafting of the manuscript: Rui Ping Meng, En Liu, and Hui Lin. Analysis and interpretation of data and acquisition of data: Bao Bao Huang, Xi Ping Liao, Jian Zhang, and Hao Qi Wei. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

| References | ▴Top |

- Ungaro R, Mehandru S, Allen PB, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Colombel JF. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 2017;389(10080):1756-1770.

doi pubmed - Feuerstein JD, Cheifetz AS. Ulcerative colitis: epidemiology, diagnosis, and management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89(11):1553-1563.

doi pubmed - Rogler G, Singh A, Kavanaugh A, Rubin DT. Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease: current concepts, treatment, and implications for disease management. Gastroenterology. 2021;161(4):1118-1132.

doi pubmed - Burger D, Travis S. Conventional medical management of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(6):1827-1837.e2.

doi pubmed - Lasch K, Liu S, Ursos L, Mody R, King-Concialdi K, DiBonaventura M, Leberman J, et al. Gastroenterologists' perceptions regarding ulcerative colitis and its management: results from a large-scale survey. Adv Ther. 2016;33(10):1715-1727.

doi pubmed - Mowat C, Cole A, Windsor A, Ahmad T, Arnott I, Driscoll R, Mitton S, et al. Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2011;60(5):571-607.

doi pubmed - Probert C. Steroids and 5-aminosalicylic acids in moderate ulcerative colitis: addressing the dilemma. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2013;6(1):33-38.

doi pubmed - Krugliak Cleveland N, Torres J, Rubin DT. What Does Disease Progression Look Like in Ulcerative Colitis, and How Might It Be Prevented? Gastroenterology. 2022;162(5):1396-1408.

doi pubmed - Le Berre C, Ananthakrishnan AN, Danese S, Singh S, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease have similar burden and goals for treatment. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(1):14-23.

doi pubmed - Solitano V, D'Amico F, Zacharopoulou E, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Danese S. Early intervention in ulcerative colitis: ready for prime time? J Clin Med. 2020;9(8):1-12.

doi pubmed - Agrawal M, Spencer EA, Colombel JF, Ungaro RC. Approach to the management of recently diagnosed inflammatory bowel disease patients: a user's guide for adult and pediatric gastroenterologists. Gastroenterology. 2021;161(1):47-65.

doi pubmed - Berg DR, Colombel JF, Ungaro R. The role of early biologic therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25(12):1896-1905.

doi pubmed - Yuan W, Marwaha JS, Rakowsky ST, Palmer NP, Kohane IS, Rubin DT, Brat GA, et al. Trends in medical management of moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis: a nationwide retrospective analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2023;29(5):695-704.

doi pubmed - Satsangi J, Silverberg MS, Vermeire S, Colombel JF. The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: controversies, consensus, and implications. Gut. 2006;55(6):749-753.

doi pubmed - D'Haens G, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Geboes K, Hanauer SB, Irvine EJ, Lemann M, et al. A review of activity indices and efficacy end points for clinical trials of medical therapy in adults with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(2):763-786.

doi pubmed - Dolinger MT, Spencer EA, Lai J, Dunkin D, Dubinsky MC. Dual biologic and small molecule therapy for the treatment of refractory pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021;27(8):1210-1214.

doi pubmed - Paramsothy S, Kamm MA, Kaakoush NO, Walsh AJ, van den Bogaerde J, Samuel D, Leong RWL, et al. Multidonor intensive faecal microbiota transplantation for active ulcerative colitis: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10075):1218-1228.

doi pubmed - Turner D, Ricciuto A, Lewis A, D'Amico F, Dhaliwal J, Griffiths AM, Bettenworth D, et al. STRIDE-II: an update on the selecting therapeutic targets in inflammatory bowel disease (STRIDE) initiative of the international organization for the study of IBD (IOIBD): determining therapeutic goals for Treat-to-Target strategies in IBD. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(5):1570-1583.

doi pubmed - Law CCY, Tkachuk B, Lieto S, Narula N, Walsh S, Colombel JF, Ungaro RC. Early biologic treatment decreases risk of surgery in Crohn's disease but not in ulcerative colitis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2024;30(7):1080-1086.

doi pubmed - Hupe M, Riviere P, Nancey S, Roblin X, Altwegg R, Filippi J, Fumery M, et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of vedolizumab and infliximab in ulcerative colitis after failure of a first subcutaneous anti-TNF agent: a multicentre cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;51(9):852-860.

doi pubmed - Feuerstein JD, Isaacs KL, Schneider Y, Siddique SM, Falck-Ytter Y, Singh S, AGA Institute Clinical Guidelines Committee. AGA clinical practice guidelines on the management of moderate to severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(5):1450-1461.

doi pubmed - Ben-Horin S, Novack L, Mao R, Guo J, Zhao Y, Sergienko R, Zhang J, et al. Efficacy of biologic drugs in short-duration versus long-duration inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and an individual-patient data meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(2):482-494.

doi pubmed - Devlin SM, Panaccione R. Evolving inflammatory bowel disease treatment paradigms: top-down versus step-up. Med Clin North Am. 2010;94(1):1-18.

doi pubmed - Faleck DM, Winters A, Chablaney S, Shashi P, Meserve J, Weiss A, Aniwan S, et al. Shorter disease duration is associated with higher rates of response to vedolizumab in patients with Crohn's disease but not ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(12):2497-2505.e2491.

doi pubmed - Ma C, Beilman CL, Huang VW, Fedorak DK, Wong K, Kroeker KI, Dieleman LA, et al. Similar clinical and surgical outcomes achieved with early compared to late anti-TNF induction in mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis: a retrospective cohort study. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;2016:2079582.

doi pubmed - Vermeire S, Hanzel J, Lowenberg M, Ferrante M, Bossuyt P, Hoentjen F, Franchimont D, et al. Early versus late use of vedolizumab in ulcerative colitis: clinical, endoscopic, and histological outcomes. J Crohns Colitis. 2024;18(4):540-547.

doi pubmed - Han M, Jung YS, Cheon JH, Park S. Similar clinical outcomes of early and late anti-TNF initiation for ulcerative colitis: a nationwide population-based study. Yonsei Med J. 2020;61(5):382-390.

doi pubmed - Boal Carvalho P, Cotter J. Mucosal healing in ulcerative colitis: a comprehensive review. Drugs. 2017;77(2):159-173.

doi pubmed - Shah SC, Colombel JF, Sands BE, Narula N. Mucosal healing is associated with improved long-term outcomes of patients with ulcerative colitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(9):1245-1255.e1248.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, including commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited.

Gastroenterology Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.